I recently gave a talk at a meeting with colleagues, most of them cardiologists and endocrinologists, where I, among other things, discussed the current status of diet-heart hypothesis and the possible relationship between our fear of dietary fats and the obesity epidemic.

After the meeting, a senior colleague of mine, an old friend, and a mentor who I deeply respect, approached me and lambasted me for several points I had made during my talk.

He said that the mortality from heart disease had dropped dramatically for the last 30-40 years, mostly because we had managed to lower blood cholesterol by making changes to our diet. He was angry with me for asking the question whether our emphasis on low-fat food products could ultimately have steered us into an epidemic of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.

During our discussion, I came to think of Dr. Tim Noakes’ words at the Foodloose Convention in Reykjavik last year where he touched upon the same issue. As a matter of fact, I had the privilege to speak at the same conference which gave me the opportunity to meet and talk with Tim for the first time.

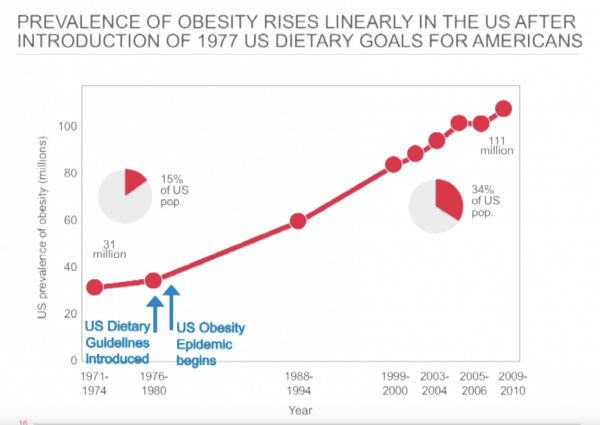

Tim showed the slide above and said;

Tim showed the slide above and said;

… the dietary guidelines changed in 1977 and in 1978 the obesity epidemic begins in the United States, and no one will take responsibility for that. And that’s the question you have to ask. You change the guidelines and why won’t you take responsibility for what happened? Why do you ignore it? And, why do you attack us for asking that question?

Yes, these were the words I remembered so vividly: … and, why do you attack us for asking that question?

The Macronutrient of Interest in Chronic Disease Is Carbohydrate, not Fat

Sixty years ago, American psychologist Leon Festinger described a phenomenon he called cognitive dissonance. He believed that we hold many cognitions about the world and ourselves; when they clash, a discrepancy is evoked, resulting in a state of tension known as cognitive dissonance (1).

Our powerful motive to maintain cognitive consistency can give rise to irrational and sometimes maladaptive behavior.

Festinger wrote:

A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.

Well, I guess you’re assuming that I think my senior colleague and old mentor suffers from cognitive dissonance. And you’re right, I do. But, I also know he thinks I’ve completely gone off the rails.

So, how can a low-fat diet lead to an epidemic of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes? Let’s start by looking at three facts.

The first one is that a low-fat diet is also a high-carb diet. Of course, this does not imply that it is a diet composed of added sugars and refined carbohydrates. However, the energy has to come from somewhere and therefore a low-fat diet is usually synonymous with a high-carb diet.

The second fact is that according to recently published evidence, at least 50% of the adult population in the U.S. have insulin resistance, manifested as diabetes or prediabetes (2).

Finally, there is evidence from several studies on human metabolism showing that insulin resistance and high-carb diets make a destructive combination. And, remember, at least half of the U.S population is insulin resistant.

Let me quote Tim Noakes’ Reykjavik lecture again:

Insulin resistance is a benign condition. However, a high carbohydrate diet turns it into a killer.

Noakes believes that the macronutrient of interest in chronic disease is carbohydrate, not fat. He says:

They completely got it wrong. Ancel Keys backed the wrong horse completely. But, this truth comes through understanding human metabolism, not epidemiology.

Insulin Resistance and High-Carb Diets – From Reaven to Noakes

Insulin resistance is defined as a diminished response to a given concentration of insulin. Initially, the pancreas responds by producing more insulin (compensatory hyperinsulinemia). For this reason, individuals with insulin resistance often have high levels of insulin in their blood (3).

Gerald M. Reaven professor emeritus in medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine was the first to emphasize the role of insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia in increasing the likelihood of developing the cluster of abnormalities commonly referred to as the metabolic syndrome (4).

The five conditions described below are used to define the metabolic syndrome. Three of them must be present in order to be diagnosed with the condition.

- Abdominal obesity, defined as waist circumference > 40 inches (102 cm) in men and > 35 inches (88 cm) in women

- A high triglyceride level in blood, defined as > 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L)

- A low HDL cholesterol level in blood, defined as < 40 mg/dL (1 mmol/L)

- High blood pressure, defined as > 130/85 mmHg or drug treatment for elevated blood pressure

- Elevated blood sugar, defined as fasting blood glucose >100 mg/dL (5.6 mo/L) or drug treatment for diabetes

The Role of Triglycerides

In his Reykjavik lecture, Tim Noakes summarized few of Reaven’s studies on the importance of triglycerides in patients with insulin resistance.

In a study published 1966, Reaven and colleagues examined the triglyceride response to low- and high-carbohydrate diets (5). They discovered that the majority of patients will increase their triglyceride concentration to a variable extent as a consequence of a high-carb diet.

Interestingly, they also found that the more insulin resistance present, the greater the subsequent rise in triglycerides following the ingestion of carbohydrates.

Reaven also suggested that endogenous hypertriglyceridemia is caused by increased triglyceride production by the liver (6). In other words, the liver is pumping triglycerides into the circulation. The higher the plasma insulin, the higher the liver production of triglycerides, the higher the blood levels of triglycerides.

Endogenous hypertriglyceridemia, which includes familial hypertriglyceridemia and idiopathic hypertriglyceridemia, is characterized by the increased level of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and triglycerides in the blood (7).

Hence, insulin resistance, accompanied by hyperinsulinemia, may be an important cause of the enhanced triglyceride production by the liver following the ingestion of a diet high in carbohydrates.

“It’s Not the Insulin Resistance per se that Is the Problem – It’s High-Carbohydrate Diets”

Reaven developed a model explaining the relationship between insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease (8).

He concluded that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are common findings in apparently healthy individuals and associated with a number of abnormalities that significantly increase the risk of coronary artery disease. Among them are lipid abnormalities commonly termed atherogenic dyslipidemia because they tend to promote atherosclerosis which is believed to be the underlying cause of cardiovascular disease.

Several bad things seem to happen if we’re insulin resistant; weight gain, atherogenic dyslipidemia, visceral adiposity, endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, hyperuricemia, systemic inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired exercise performance.

Noakes believes Reaven’s biggest mistake was to not pinpoint high-carbohydrate diets as the culprit. However, Noakes refers to three papers published by Reaven’s group between 1987-1994 to emphasize that Raven knew that carbohydrate was the villain.

Noakes says:

So, Reaven understood that carbohydrates drive insulin secretion in the metabolic syndrome. Hence he had to conclude that restricting carbohydrate should be the key therapy for this condition. In 1987 he was heading into that conclusion because he published three papers in 1987, 1989 and 1994 all showing the benefits of low carbohydrate diets in people with insulin resistance.

The studies Noakes is referring to were performed on individuals with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM); a group that is highly representative for insulin resistance. Here are Reaven’s main conclusions from these three papers (9,10,11):

These results document that low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets, containing moderate amounts of sucrose, similar in composition to the recommendation of the ADA, have deleterious metabolic effects when consumed by patients with NIDDM for 15 days. Until it can be shown that these untoward effects are evanescent and that long-term ingestion of similar diets will result in beneficial metabolic changes, it seems prudent to avoid the use of low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets containing moderate amounts of sucrose (9).

The results of this study indicate that high-carbohydrate diets lead to several changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in patients with NIDDM that could lead to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, and that these effects persist for more than 6 weeks. Given these results, it seems reasonable to suggest that the routine recommendation of low-fat high-carbohydrate diets for patients with NIDDM be reconsidered (10).

In NIDDM patients, high carbohydrate diets compared with high monounsaturated fat diets caused persistent deterioration of glycemic control and accentuation of hyperinsulinemia, as well as increased plasma triglycerides and VLDL-cholesterol levels which may not be desirable (11).

Then Noakes says:

Why did he (Reaven) stop in 1994 doing low carbohydrate studies? The answer is that because he was at Stanford which is one of the most progressive cardiovascular groups. Had he came out in 1994 and said you must all eat a high-fat diet, his career would have ended overnight. And wisely he decided to continue researching without drawing attention to himself and that’s why that work is so fundamental but it has got lost.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and other Western countries (12).

It is primarily triglycerides that accumulate in the liver in patients with NAFLD. Triglyceride accumulation may be due to an excessive importation of free fatty acids to the liver from adipose tissue. Excessive amounts of fatty acids may also be produced by the liver cells themselves due to an increased conversion of carbohydrates and proteins to triglycerides. Defective transport of fatty acids from the liver may also contribute to the accumulation of triglycerides in the liver.

A paper published 2016 suggests that the presence of NAFLD in people with insulin resistance is a key driver of atherogenic dyslipidemia so typical of the metabolic syndrome (13).

Patients with NAFLD are more likely to have high levels of apolipoprotein B and small LDL particles, regardless of similar body mass index and other clinical parameters. The authors speculate that this lipoprotein profile is driven mostly by liver fat content and insulin resistance and appears not to be worsened by obesity or the severity of liver disease. Hence, NAFLD may be a major link between insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and coronary heart disease.

In his Reykjavik lecture, Noakes said:

What they are showing for the first time is that the key driver of atherogenic dyslipidemia is NAFLD. And, how do you get NAFLD? You get it from eating a high carbohydrate-diet feeding insulin resistance.

The Bottom Line

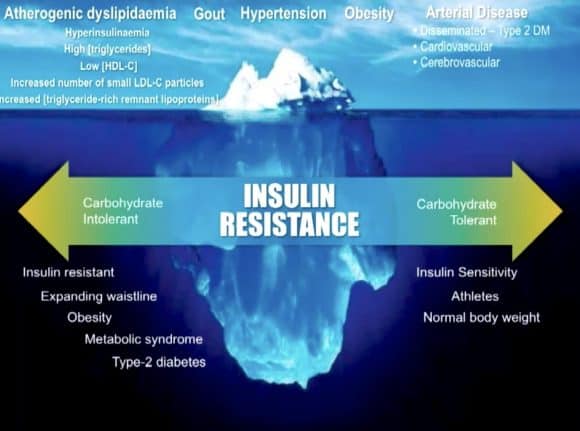

Noakes does an excellent job in explaining the clinical implications of the metabolic abnormalities underlying insulin resistance, visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease, and how these may be fueled by high consumption of carbohydrates.

You’re either highly carbohydrate tolerant, normal or carbohydrate intolerant. If you’re tolerant, you’re probably an athlete, probably not overweight or obese, and you’ll probably not get these diseases, and you can eat pretty much what you like.

But if you’re carbohydrate intolerant, there’s only one way you can go; insulin resistance, expanding waistline, obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes await you.

Noakes says:

And that’s the point when we’re talking about nutrition. Nutrition is not the issue. It’s the patient. And you’ve got to fit the diet the patient. People just don’t seem to get it; If you’re insulin resistant you cannot eat carbohydrates.

Noakes is convinced that a low-carbohydrate diet is a key to the prevention and treatment of insulin resistance and all its associated conditions.

If he’s right, advising everybody to consume a low-fat, high-carbohydrate may be catastrophic because at least 50% of the adult population is insulin resistant. If we put all these insulin resistant people on a high-carb diet, we may have an epidemic of obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

Sounds familiar huh?

Discover more from Doc's Opinion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

In the 1990’s, Iceland was the European Champion of transfat consumption:

https://www.mast.is/…/Reglugerdumtransfitusyrur301110.pdf

The authors of the Icelandic epi-study noted themselves.

“Further, the supply of margarines made from hydrogenated fats and used for cooking and baking, has plummeted by 73% (from 11.7 kg/person/year to 3.2 kg/person/year), the largest drop occurring in the 1990s, when the most significant drop in cholesterol was also seen.”

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article…

In Denmark, when introducing the ban on transfats, this happened:

https://sciencenordic.com/danish-ban-trans-fat-saves-two…

https://www.ajpmonline.org/…/S0749-3797(15)00328-1/fulltext

Considering “the mean daily intake of artificial trans fat in Denmark was about 1 gram in 2001” and in Iceland in the 1990’s we were consuming over 5g on average, I personally would consider it very likely that this change would explain most, if not all of the CV benefits that correlate with changes in the diet in that study.

To me, lumping SFA from minimally processed animal products with industrial transfats, is like lumping cyanide with vegetables – there is no meaningful outcome.

Thanks Guðmundur.

I agree with you. We may very well have underestimated the effect of reduced intake of trans fats.

Interestingly, the AHA just release a Presidential advisory underscoring the importance of reducing saturated fat. And now w’re even back to replacing them with carbs: “… good carbohydrates,” such as whole grains and whole fruits, are other appropriate foods to substitute for saturated fats.

Interestingly, there’s no mention whether this should apply to those with metabolic syndrome or diabetes. So, they continue to advise the same diet for everybody.

Quote:

“There has been concern about various unqualified individuals — self-proclaimed experts who are promoting a new book or suchlike — touting the idea that saturated fat is good for you, which has attracted a lot of media attention,” said David Jenkins, MD, Departments of Nutritional Sciences and Medicine, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, who was not a part of the advisory writing group.

“But the AHA has always taken the stance that saturated fat is bad and that we should be eating more plant oils, and this view is endorsed by the vast majority of nutritionists who are scientifically qualified,” he told Medscape Medical News.”

And, recommending a different approach may even cost lives:

“Dr David Katz said the paper was well timed. It is clearly responsive to the many high-profile and misguided efforts to discredit the well-substantiated links between saturated fat in the diet and blood lipids and between blood lipids and cardiovascular disease. Misrepresentations in these areas have real potential to cost lives, so this paper is an urgently needed, well-timed, and impressively evidence-based reality check.”

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/881689?pa=WD7A0%2Fh03miQ7G3dFYn8L0q%2BCFYtiVED5A6NCJNiVz9bbZ7n8mcuiFjSonFj2yXQ8SIvl8zjYv73GUyW5rsbWA%3D%3D

Good news for the United States is that one year from now (June 18, 2018), Trans Fats will be banned over here as well, with an estimated savings of over 90,000 premature deaths a year. The German born scientist credited for discovering the link in the 1950’s, and lobbying decades to get it banned, was Fred Kummerow. His diet included red meat, whole milk and eggs saturated in butter. He lived age of 102 with a sharp mind, but sadly passed away a few weeks ago. He also helped to discover it was oxidized cholesterol, rather than cholesterol alone, that is the link to disease.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/01/science/fred-kummerow-dead-biochemist-ban-trans-fatty-acids.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fred_Kummerow

Another good sign over here is that smoking rates are dropping. Smoking is no longer perceived as cool thing to do, but is something stupid people do. When smokers were told about the health damage, it did nothing to deter them; but when public opinion labeled them as idiots, they stopped.

“He said that the mortality from heart disease had dropped dramatically for the last 30-40 years, mostly because we had managed to lower blood cholesterol by making changes to our diet. ”

We get this criticism in New Zealand too, but the food statistics don’t bear it out. Saturated fat intake did drop at the same time as CVD mortality, (from around 1970) but SFA intake declined very slowly indeed, whereas CVD mortality dropped more sharply. SFA was mainly replaced with refined carbs – MUFA went down a bit and PUFA only went up slowly, only by around 2% of energy over 2 decades.

These are not changes that would be predicted to make much of a difference according the various substitution meta-analyses.

What else changed?

1) not only did smoking rates begin to drop around 1970, but filter-tipped cigarettes replaced the once-common unfiltered brands during the 1960’s and 70’s.

2) frozen veges became accessible year round as more people bought fridges

3) fortification of processed food added more micronutrients to the food supply

4) wholegrain breads and yoghurt (etc), unknown foods in the 1960s, were commonly used by the end of the 1970s.

5) restrictions were put on smoke emissions, vehicle exhausts, workplace pollutants, and the use of persistent pesticides during the 1970s

6) amphetamines and barbiturates were phased out during the 1960’s, warfarin and TNT became more widely used, ditto blood pressure meds. No doubt many a cardiotoxic drug has been quietly discontinued.

These changes can I think account for a significant reduction in CVD mortality; the SFA/PUFA changes here were too little too late to take the credit.

Thanks for the comment George. I agree that all these facts that you mention could have contributed to the decreasing mortality and morbidity from coronary heart disease. There are probably other unknown factors as well. Oversimplifying the issue seems pretty naive.

Axel, doesn’t animal protein also lead to insulin resistance? I saw this study as an example https://cdn.nutrition.org/content/1/4/e000299

And what of the increases in IGF-1 from animal protein? Is that not significant if we are to shift away from carbs?

Or Is this piece meant to more to guide us away from carbs to fat as a preferred dietary source?

As always, an interesting read.

Multiple mechanisms are responsible for insulin resistance including genetic or primary target cell defects, autoantibodies to insulin, accelerated insulin degradation and much more.

Obesity is probably the most common cause of insulin resistance.

However, I’m not really digging into the causes of insulin resistance here, but rather highlighting a school of thought implies that the type of high-carb diet often recommended by public health authorities, may make people with insulin resistance sicker than they already are. According to that same school of thought, a low-carb, high-fat diet could help make insulin resistance pretty harmless.

Hi Axel,

Healthline would like to congratulate you on making our list of the Best Heart Disease Blogs of 2017!

Our editors carefully selected the most up-to-date, informative, and inspiring blogs that aim to uplift their readers through education and personal stories. We’re glad to have you on the list!

We’ve created a badge that you can embed on your site to let your readers know about your win. The embed code is at the link below.

Winners list: https://www.healthline.com/health/heart-disease/best-blogs-of-the-year

Badge to embed: https://www.healthline.com/health/heart-disease/best-blogs-badge-2015

If you have any questions or need help embedding the badge, feel free to be in touch. Congratulations and keep up the great blogging!

Warmly,

Maegan

—

Maegan Jones | Content Coordinator

Healthline

Your most trusted ally in pursuit of health and well-being

Thank you so much Maegan.

I highly appreciate it.

I’ve already embedded the badge

I have NAFLD, hypertension, lipid problem, central obesity. Family history of heart disease & stroke. All symptoms started after menopause. Started low carb/mediterranean diet. Down 15 lbs & normal BP in 2 months. However, I’m not sure how low my low carbohydrate diet should be. Any suggestions on grams per day?

I like crab meat very much, so I’m glad it’s low in calories.