Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

“Lack of activity destroys the good condition of every human being, while movement and methodical physical exercise save it and preserve it.” — Plato (427–347 BC)

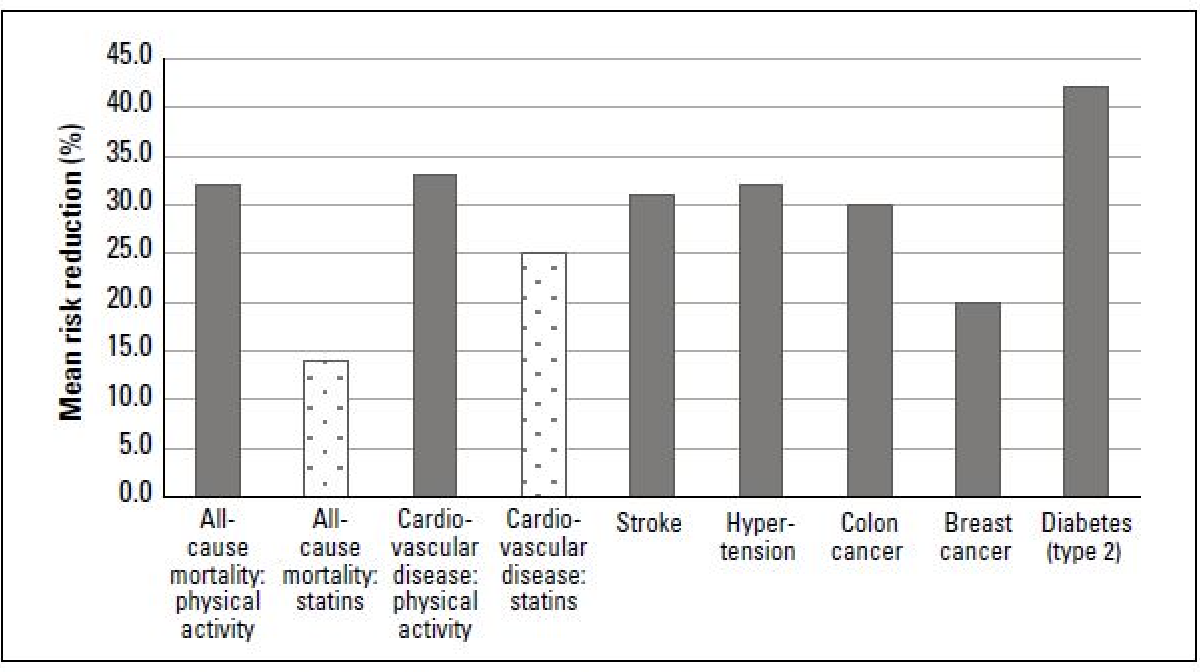

Physical inactivity is a serious health problem worldwide. In contrast, regular exercise is associated with several health benefits. These include lower risks of developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, and some cancers.

In the early 1950s, researchers observed that drivers of London’s double-decker buses were more likely to suffer fatal heart attacks than the conductors. The drivers were sedentary (sitting for more than 90% of their shifts) whereas the conductors were physically active (climbing roughly 500 to 750 steps a day) (1).

Another study published a few years later found that the risk of heart attack was higher among government clerks than physically active postal workers (2).

Consequently, it was concluded that men in physically active jobs have a lower risk of heart disease than men in physically inactive jobs.

In this article, I review the scientific evidence behind the proposed health benefits of physical activity and exercise. I also discuss the role of aerobic and strength training respectively and the health benefits of physical fitness. Finally I address the possible risks of physical exercise and how much activity is needed to gain health benefits.

The term “physical activity” should not be confused with “exercise”, which is a subcategory of physical activity. Here, the term physical activity is used to describe any type of physical movement, including occupational, household, and leisure time activities. Physical exercise, on the other hand, refers to a form of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful, aimed at improving and maintain physical fitness (3).

The Scientific Evidence

Most of the evidence for the benefits of physical activity and exercise comes from long-term observational studies.

Observational studies observe the effect of a risk factor (e.g., smoking, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol or, in this case, the degree of physical exercise), diagnostic test, treatment or other intervention, without trying to influence who is or isn’t exposed to it. Cohort studies and case control studies are two types of observational studies.

Most observational studies show that physical activity and regular exercise are associated with several beneficial health outcomes. In contrast, sedentary behavior is associated with a variety of poor health outcomes.

Unfortunately, this type of evidence is subject to bias. The decision to exercise may simply be one of many choices made in adopting a healthy lifestyle. Hence, the attribution of physical activity and exercise may be confounded by other favorable risk characteristics (4).

For example, individuals who exercise regularly are more likely to adopt a healthy eating pattern and to avoid smoking.

Unfortunately, the evidence of prospective, randomized clinical trials to establish the benefits of physical activity and exercise is limited. Such studies are difficult to perform, largely because individuals initially randomized to physical inactivity may start engaging in exercise and vice versa. The crossover between groups will make the scientific evaluation of the value of exercise almost impossible.

Nevertheless, randomized trials on the benefits of exercise have been performed. However, they have usually involved a small number of patients and the results have been inconclusive.

Most of the evidence for the benefit of physical activity and exercise comes from long-term observational studies. These studies show that physical activity and regular exercise are associated with several health benefits. The evidence from prospective, randomized clinical trials to establish the benefits of physical activity and exercise is limited.

The Role of a Sedentary Lifestyle

One out of five adults around the world is believed to be physically inactive. Physical inactivity is more prevalent among wealthier and urban countries and women and elderly individuals (5).

A sedentary lifestyle can be defined as a type of lifestyle with little or no physical activity. Sedentary behavior includes tasks such as sitting, reading, driving a car, computer use, watching television, office work, and cell phone use.

In 2002, The World Health Organisation (WHO) issued a warning that a sedentary lifestyle could very well be among the ten leading causes of death and disability in the world (6).

Sedentary lifestyle increases all causes of mortality and doubles the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity. It also increases the risks of colon cancer, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, lipid disorders, depression, and anxiety (6).

Approximately 12 percent of deaths in the United States are related to the lack of physical activity. Furthermore, a sedentary lifestyle may double the risk of coronary heart disease (4).

A large study published in 1993 concluded that physical inactivity was the second leading single external (non-genetic) cause of death in the United States, trailing only tobacco use (7).

Physical inactivity is also associated with an increased risk of worsening of many chronic health conditions. These include cardiovascular disease, heart failure, stroke, certain cancers, osteoporosis, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension (8).

Numerous observational studies have shown indicators of physical inactivity, such as TV viewing, driving in a car and sitting, are strongly related to the risk for developing adverse blood lipids (9), obesity (10, 11), type 2 diabetes (12, 13, 14), hypertension (15, 16), metabolic syndrome (17), and cardiovascular disease (9, 10, 11, 15).

A recent systematic review found that higher levels of total daily sitting time were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, independent of physical activity (18). The findings support that public health guidelines should focus on reducing total daily sitting time.

A sedentary lifestyle can be defined as a type of lifestyle with little or no physical activity. Sedentary behavior includes sitting, reading, driving a car, computer use, watching television, office work, and cell phone use. The amount of time spent on these indicators of physical inactivity is associated with increased risk of abnormal blood lipids, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Strength Training, Muscular Strength and Health Outcomes

Aerobic exercise, also referred to as endurance training or cardiovascular training, includes any activity that improves cardiovascular and pulmonary fitness. Examples of aerobic exercise include walking, running, swimming, cycling, and rowing.

Strength training is a type of physical exercise that uses resistance to induce muscular contraction. This type of training builds the strength, anaerobic endurance, and size of skeletal muscles (19).

Strength training can be performed using body weight resistance (eg, push-ups), free weights (eg, barbell squats), or other tools, and resistance bands that place loads on muscles forcing them to work harder. Strength may be displayed dynamically, as in weightlifting or running, or statically, as in activities like gymnastics and yoga (20)

Muscular strength is defined as the ability to produce force against resistance (21).

Observational studies show that both aerobic exercise and strength training are associated with positive health outcomes.

The Prospective Urban-Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study is a large, longitudinal population study done in 17 countries. Participants in the study were assessed for grip strength. The results of this part of the study were published in Lancet in 2015 (22).

Low grip strength was associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-cardiovascular mortality, heart attack, and stroke. Low grip strength was a stronger predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than systolic blood pressure.

A 2017 study tested the association between grip strength, obesity, and mortality. Data from 403.199 participants in the UK Biobank study were used in the analysis. The study showed that obese individuals with greater muscle strength have lower risks of mortality, independent of the degree of obesity (23).

There is overwhelming evidence that muscular strength and strength training are associated with several health benefits and increased life expectancy (24).

Older adults who perform strength training not only improve their physical condition but their survival rate is improved as well (25).

Resistance training counteracts the age-related decline in muscle mass and strength, improves balance and coordination, and reduces the risk of osteoporosis (26).

Strength training may also reduce insulin resistance and improve blood pressure and blood lipids.

Strength training is a type of physical exercise specializing in the use of resistance to induce muscular contraction. This type of training builds the strength, anaerobic endurance, and size of skeletal muscles. Muscular strength is defined as the ability to produce force against a resistance. There is overwhelming evidence that muscular strength and strength training are associated with several health benefits and increased life expectancy.

Physical Fitness and Health Outcomes

Physical fitness is to a large extent determined by physical activity performed over the last weeks or months. It refers to a good physical condition as a result of exercise and proper nutrition.

Physical fitness can be divided into three categories (27):

- Aerobic fitness (cardio-respiratory capacity)

- Strength and endurance

- Flexibility

Aerobic fitness is the ability of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems to supply oxygen to large muscle groups over an extended time. Examples of aerobic activities include running, cycling, and swimming.

Strength is the ability to produce force against resistance. Muscular endurance is the ability to repeat a motion against resistance multiple times.

Flexibility is the ability to stretch muscles and joints.

Several scientific studies show that high physical fitness is associated with improved health outcomes.

Higher levels of physical fitness appear to delay all-cause mortality primarily due to lowered rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer (28,29).

Men who maintain or improve their physical fitness are less likely to die from all causes and cardiovascular disease during follow-up than persistently unfit men (30).

Young individuals with low physical fitness are 3- to 6-fold more likely to develop diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome than individuals with high fitness (31).

In a cohort of healthy middle-aged adults, fitness was significantly associated with a lower risk of chronic disease outcomes during 26 years of follow-up. These findings suggest that higher midlife fitness may be associated with better health at old age (32).

High levels of physical fitness are associated with improved health outcomes. Higher physical fitness appears to delay all-cause mortality primarily due to lowered rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Individuals with low physical fitness are at higher risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.

The Effects of Physical Activity and Exercise on Health Outcomes

Mortality

Large observational studies indicate that physical activity and regular exercise reduces the risk of mortality for most individuals.

Higher recreational and non-recreational physical activity is associated with a lower risk of mortality in individuals from low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries (33).

Another study found that leisure-time physical activity was inversely associated with all-cause mortality in all age groups. A benefit was found from moderate leisure-time physical activity, with further benefit from sports activity and bicycling as transportation (34).

Daily physical activity is strongly associated with a lower risk of mortality in healthy elderly people. Simply expending energy through any activity may influence survival in older adults (35).

Hence, increasing physical activity is a simple, widely applicable, low-cost global strategy that could reduce the risk of premature deaths in all people.

Cardiovascular Disease

Numerous observational studies show an association between regular exercise and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

It has been found that leisure‐time physical activity is effective in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Such activity is associated with an approximately 20% reduction in cardiovascular events and an increase in life expectancy of approximately 5 years. In this respect, high cardiovascular fitness as a result of vigorous activity levels seems to be more important than total activity time (36).

People who achieve total physical activity levels several times higher than the current recommended minimum level have a significant reduction in the risk of coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, breast cancer, colon cancer, and diabetes (37).

Clinical trials show that all activities, including aerobic exercise and weight training, lower blood pressure. Daily activity produced greater blood pressure reduction than when performed three times per week. Hence, physical activity has an independent capacity to lower blood pressure (38).

Evidence also suggests that physical activity may reduce the risk of stroke (39).

Aerobic training has beneficial effects on blood lipids such as LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and non-HDL cholesterol (40).

Furthermore, evidence suggests that increased exercise is associated with reduced inflammation (41).

Cancer

Observational evidence shows that physical exercise is associated with reduced risk of cancer (42).

Epidemiologic data from 73 studies conducted around the world show a 25% reduction in the risk of breast cancer among the most physically active women compared with those who are least active (43).

A meta-analysis of 19 studies showed that physical activity is associated with reduced risk of cancer of the kidney (44).

Similarly, numerous studies have established the protective role exercise plays in decreasing the risk of many other cancers, including lung, endometrial, colon, and possibly prostate cancer (45, 46, 47, 48).

Diabetes

Regular physical exercise may prevent or delay the development of type 2 diabetes (49).

Besides, physical exercise improves blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes, reduces cardiovascular risk factors, contributes to weight loss, and improves well-being (50, 51).

Regular exercise also has considerable health benefits for people with type 1 diabetes, including improved cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength, and insulin sensitivity (52).

Obesity

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased substantially across the globe during the last few decades. This is a major public health concern because the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, certain types of cancers, and even mortality is directly proportional to the degree of obesity (53, 54).

Compared with a weight loss diet alone, diet coupled with either aerobic and/or resistance training is associated with a greater reduction in body fat compared with a weight loss diet alone (3).

Furthermore, aerobic exercise and resistance training, even in the absence of caloric restriction, may result in weight loss and a reduction in body fat (55, 56, 57).

However, it has not been firmly established that exercise contributes significantly to weight loss in obese individuals. Nevertheless, physical activity of all types, will likely lead to several health benefits in people with obesity.

Infections

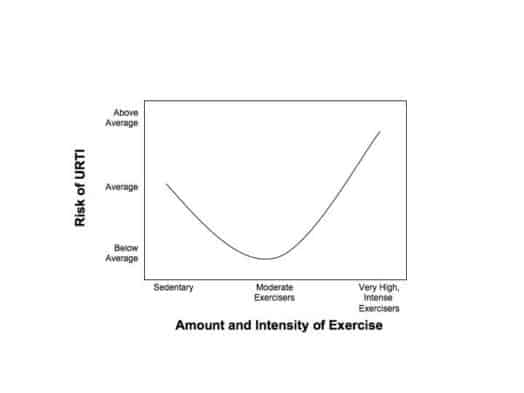

Results from randomized clinical trials and epidemiologic studies suggest that moderate exercise training reduces the risk of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). Several epidemiologic studies also suggest that regular physical activity is associated with decreased mortality and incidence rates for influenza and pneumonia (58).

Regular physical activity and frequent exercise may limit or delay the decline in immune function usually associated with aging (59). Thus, leading an active lifestyle may benefit immune function. This may improve health and reduce the risk of disease in older age.

There is some evidence that intense training is associated with higher levels of infection. It has been proposed that the relationship between the intensity of exercise and URTIs may be described by a J-curve. Such a relationship suggests that regular moderate-intensity exercise decreases the risk of URTIs compared to sedentary individuals, while a sedentary lifestyle and strenuous intense exercise increase the risk of URTIs (60).

Osteoporosis

During the first three decades of life, bone mass depends to a large degree on levels of physical activity. In women, bone mass begins to decrease around the age of 30 years, often leading to osteoporosis after menopause. Osteoporosis increases the risk of bone fracture and back pain. Thus, it is a major contributor to individual suffering and represents a significant socioeconomic burden (61).

Weight-bearing exercise is associated with increased bone mineral density. Also, exercise is associated with a decreased risk of hip fractures among patients with osteoporosis (3).

Randomized clinical trials strongly support the view that regular exercise programs are effective in preventing or treating osteoporosis (62).

Cognition

The term cognition refers to the ability to think. It describes the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and processing by thought, experience, and the senses.

Exercise has been associated with improved cognitive function in both young and older adults (63, 64, 65).

Recent study results demonstrate that physical exercise has beneficial effects on cognition and lowers the risk of dementia (66).

Psychological Effects

Regular physical exercise is associated with improved sleep, reduced stress and anxiety as well as a lower risk of depression (67, 68).

A large meta-analysis presents compelling evidence supporting exercise as an evidence-based intervention to improve sleep in healthy individuals. The results indicate that the benefits of exercise for sleep are realized immediately, with exercise having an acute positive impact on many important objective metrics of sleep. Furthermore, the results suggest that regular exercise leads to even greater subjective and objective sleep benefits over time (69).

A population-based study showed that exercisers are on average less anxious and depressed, less neurotic, more extroverted, higher in thrill and adventure seeking than non-exercisers (70).

Regular physical exercise can promote a variety of psychological and physiological conditions that may be beneficial in the primary care of adolescent females with depressive symptoms (71).

Regular physical activity and exercise are associated with a lower risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and upper respiratory tract infections. Furthermore, physical exercise appears to improve sleep, reduce stress and anxiety as well as lower the risk of depression.

The Risks of Exercise

The benefits of physical activity far outweigh the possible associated risks in most individuals.

Musculoskeletal injury is the most common health risk associated with exercise. Various types of strains and tears, inflammation of tendons, and bone fractures may occur as a result of physical activity

More serious but much less common issues include sudden cardiac arrest, and myocardial infarction (heart attack).

Breakdown of skeletal muscle (rhabdomyolysis) may occur following extreme exertion. Massive rhabdomyolysis may lead to kidney failure and several other abnormalities.

Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) and Acute Myocardial Infarction

The risk of acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) and sudden cardiac death (SCD) is increased during and shortly after bouts of vigorous physical exertion (72).

The proportion of sudden deaths that occur during physical exertion is higher in younger age groups (73 ,74).

The proportion of sudden deaths that occur during physical exertion in competitive athletes <35 years of age is much higher than in non-athletes in the general population (75,). However, the absolute numbers of sudden cardiac deaths are greater during recreational sports and most of these occur in adults > 35 years of age (76).

Acute heart attacks also occur with higher than expected frequency during or soon after physical exercise. Exercise is also a trigger for acute type A aortic dissection, which has been reported in alpine skiers and weight lifters (72). Aortic dissection occurs when an injury to the innermost layer of the aorta allows blood to flow between the layers of the aortic wall.

There is an increased relative risk of acute cardiac events with unaccustomed vigorous physical exercise. However, the absolute risk of experiencing SCD or heart attack during physical exertion is very small.

Strenuous physical activity, especially when sudden and unaccustomed, increases the risk of heart attack and SCD. This includes sports such as racket sports, downhill skiing, marathon running, triathlon participation, and high-intensity sports activities (eg, basketball, soccer)(77. 78, 79, 80, 81).

Those at highest risk of exercise-related SCD are individuals with heart failure or a previous history of a heart attack.

Exercise-related SCD in the young is often related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. However, in many cases, no identifiable cause can be found at autopsy and these deaths are often classified as either sudden arrhythmic death or SCD with a structurally normal heart (82).

The benefits of physical activity far outweigh the possible associated risks in most individuals. Musculoskeletal injury is the most common health risk associated with exercise. There is an increased relative risk of acute cardiac events with unaccustomed vigorous physical exercise. However, the absolute risk of experiencing sudden cardiac death or heart attack during physical exertion is very small.

How Much Activity Will Improve Health? Does Too Much Exist?

International guidelines, recommend regular exercise training as a cornerstone for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. In general, >150 minutes of endurance exercise training per week at moderate to vigorous intensity, ideally spread over 3 to 5 days, is recommended (83).

This recommendation is associated with a 20% to 30% lower risk for premature all-cause mortality and incidence of many chronic diseases, with greater health benefits for higher volumes and greater intensities of activity (84).

Long-term intense exercise training alters cardiac structure and function. The athlete’s heart is characterized by an enlargement of the cardiac chambers, improvement of cardiac function, and slow heartbeat. These adaptations are believed to be benign (72).

Emerging evidence, however, suggests that over time, high-volume, high-intensity exercise training can induce cardiac maladaptations such as

an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, coronary artery calcification, and fibrosis of the heart muscle. Hence, it is currently debated whether intensive exercise can be harmful to the heart (72).

Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is characterized by a chaotic electrical activity of the atria leading to rapid, irregular heart rhythm (85). It is the most common arrhythmia in the general population.

There is evidence that fitter individuals have the lowest risk of atrial fibrillation. However, there is substantial evidence that the risk for atrial fibrillation is higher in athletes than in control subjects (72).

In the US Physician’s Health Study, men who jogged 5 to 7 times per week had a 50% higher risk of atrial fibrillation than men who did not exercise vigorously (86).

Three meta-analyses found that the risk of atrial fibrillation was 2- to 10-fold higher in endurance athletes than in control participants (86, 87, 88).

The mechanisms responsible for the increased risk of atrial fibrillation among athletes are unknown. However, enlargement of the atria following many years of training may play a role. (89).

Coronary Artery Calcification

Exercise training reduces the risk of symptomatic coronary artery disease and clinical cardiovascular events (90, 91). Nevertheless, accelerated atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries has been found among athletes. For example, high coronary calcium scores seem to be more common among marathon runners and male amateur athletes compared with non-athletes (92, 93).

The clinical relevance of accelerated coronary artery atherosclerosis in athletes performing a very high-volume or high-intensity training is unclear. Although elevated coronary calcium scores in athletes might indicate increased cardiovascular risk, definite data to support this hypothesis is lacking (94).

Most active athletes seem to have fewer unstable “mixed” plaques despite their more stable calcified plaques. Mixed plaques are associated with a high risk of cardiac events, whereas calcified plaques are associated with lower risk (95).

Regular exercise training is a cornerstone for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Emerging evidence, however, suggests that over time, high-volume, high-intensity exercise training can induce cardiac maladaptations. These include an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, coronary artery calcification, and fibrosis of the heart muscle.

“If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the safest way to health”. – Hippocrates

what do you consider to be high-intensity exercising? where lies the balance: not too much, not too little? And thank you for this report Dr. Sigurdsson,

with kind regards, Barney R

A very relevant question indeed Barney. And, typically, I cannot give you a clear cut answer.

Either the curve is curvilinear meaning that the more you exercise the more the health benefits, or it is a J-curve where at a certain point there is a loss of health benefits.

Currently there is no compelling evidence to reject the curvilinear association. However, if the curve is J-shaped we don’t really know at which point you start to do harm but things like triathlon an running a marathon will probably fall into the “too much” category when it comes to health risks.

Take look at figure 8 in the below paper where these issues are explained nicely:

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000749

thank you for your response and for the aha study attached. i was curious, however, yet i personally don’t feel in danger of exercise high-intensity as at eighty-two i subscribe to the “keep-moving” maxim. it is true for me that when things are going quite well, i run the risk of over-doing where the consequences result in injury. Vigilance should be my exercise mantram. i would hope that more studies will come forth discussing risks and dangers and that they may be picked up by, say, Gretchen Reynolds who writes the PhysEd piece in Tuesday’s Science Times in the New York Times or in other news reports.

Barney

During which person’s heart rate reaches at least 80 percent of it’s maximum capacity usually for one to five minutes,with periods of rest or less intense exercise.