Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

Arrhythmia is a term that is used to describe disorders of heart rhythm. It may be an irregular rhythm, or rapid or slow beating of the heart.

Although most arrhythmias are completely innocent, some may need medical attention, and a few are life-threatening.

The term palpitations describes an awareness of heart muscle contractions in the chest. These are often described as hard beats, fast beats, irregular beats, skipped beats or “flip-flopping”.

Palpitations are most often caused by premature contraction of the upper or lower chambers of the heart. Such symptoms are very common, and in most cases, they are completely benign.

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is the most common arrhythmia needing medical attention. During the last few years, the prevalence of atrial fibrillation has increased rapidly (1).

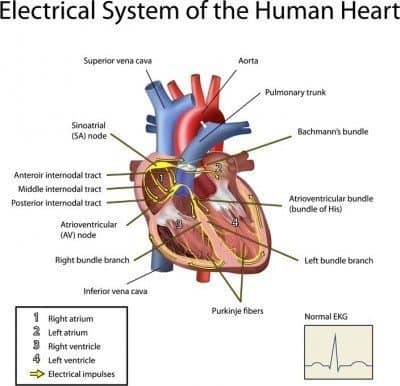

The Electrical System of the Heart

The heart has its physiological pacemaker, the sinus node (SA node), in the upper right chamber of the heart, right atrium. The sinus node emits more than 2.5 billion electric pulses during a lifetime.

Although a normal resting pulse may vary between 40 to 100 per minute, the sinus node, influenced by signals from the nervous system and endocrine organs, adjusts the heart rate to meet demands such as during physical exercise.

Normal heart rhythm originating from the sinus node is termed sinus rhythm.

Next, the signals travel to the area that connects the atria with the the lower chambers of the heart (the ventricles), the atrioventricular node (AV node) and from there through an area called the AV bundle, or the bundle of His.

The bundle of His splits into thinner branches (right and left bundle branches) that extend to the right and left ventricles. Finally, the signals reach the muscle cells of the ventricles, causing them to contract.

The Electrical Characteristics of AFib

The term tachycardia is used to describe rapid beating of the heart while the term bradycardia describes slow heart rate.

Tachycardias originating in the atria are usually far better tolerated than those originating in the ventricles (ventricular tachycardia).

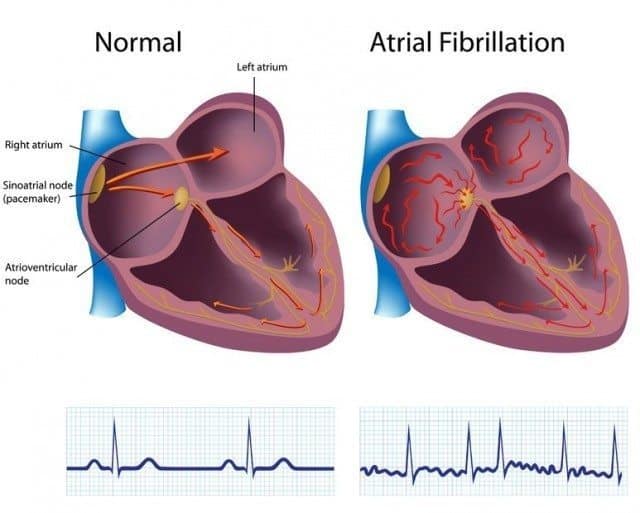

Atrial fibrillation is characterized by a chaotic electrical activity of the atria leading to rapid, irregular heart rhythm. The atria discharge at a very fast rate, exceeding 300 per minute or faster. But, fortunately, these rapid electrical impulses cannot reach the ventricles without traversing the AV node.

The AV node reduces the impulses reaching the ventricles by about two-thirds. While the resulting heart rate is rapid and irregular, it can often be tolerated for long periods.

Epidemiology and Underlying Causes of AFib

Despite many years of research and recent advances, the precise mechanisms underlying atrial fibrillation are not exactly understood. Changes in the electrical characteristics of atrial cells are believed to be important.

Atrial fibrillation is more common in men than women and its prevalence increases with age (2). Atrial fibrillation’s growing prevalence is partly explained by the aging of the population.

Many patients with atrial fibrillation have underlying disorders that increase their risk of arrhythmias such as congenital heart disease, high blood pressure, valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease or obstructive sleep apnea. Rheumatic heart disease, although now uncommon in developed countries, is associated with increased risk of atrial fibrillation.

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) has been associated with increased risk of atrial fibrillation (3)

Having a family history of atrial fibrillation increases the risk of the disorder.

Classification of AFib

The clinical picture of atrial fibrillation varies. Some people only experience a few short periods of atrial fibrillation throughout their lifetime, and in some, atrial fibrillation is constantly present.

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation is defined as atrial fibrillation that terminates spontaneously or because of specific treatment within seven days of onset. It is sometimes called occasional, self-terminating or intermittent atrial fibrillation.

Persistent atrial fibrillation is defined as atrial fibrillation that persists for more than seven days.

Permanent atrial fibrillation is defined as persistent atrial fibrillation where a clinical decision has been made to not aim at restoring normal sinus rhythm.

Lone atrial fibrillation is a term that was often used in the past to describe atrial fibrillation that occurred in people without underlying heart disease (4). This distinction was believed to be important because when there is a known underlying cause for the arrhythmia, such as heart surgery, heart attack, thyroid dysfunction or lung disease, treatment is directed toward the underlying disease as well as the atrial fibrillation itself.

Lone atrial fibrillation identifies a group of individuals with low risk of complications. Affected individuals are often younger than those with underlying heart disease and more likely to be males. It accounts for between 25-45 percent of cases of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (5).

History and Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation is based on history, physical examination, and an electrocardiogram (ECG). Further evaluation aims at identifying or excluding underlying heart disease.

History

Patients with atrial fibrillation commonly experience palpitations, such as fast and irregular heart beat. Some experience breathlessness or reduced exercise tolerance. Fatigue, dizziness, light-headedness and increased urination may also be present.

However, not all patients with atrial fibrillation are symptomatic. In these cases, atrial fibrillation is often incidentally discovered on physical examination or by an electrocardiogram.

Sometimes atrial fibrillation is preceded by physical exercise, emotional stress or alcohol.

Diagnostic Evaluation

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to verify the presence of atrial fibrillation.

Further testing aims at identifying risk factors and excluding the presence of underlying heart disease.

An ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) is usually recommended. It provides information about the condition of the heart valves, the size of the atria and the function of the left and right ventricle.

Exercise testing is sometimes performed if coronary heart disease is suspected.

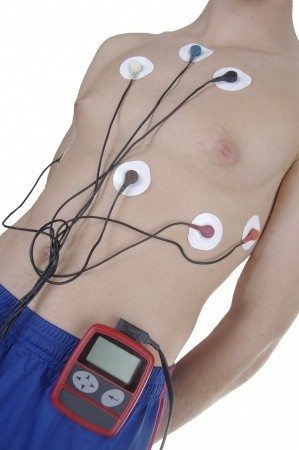

Holter monitors or event recorders are small devices that the patients may carry with them for long-term registration of heart rhythm. They may help to identify episodes of intermittent atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation is sometimes associated with disorders of the thyroid gland. Therefore, a blood test for analysis of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free T4 levels is usually recommended.

Treatment of AFib

Two important management issues have to be addressed when treating atrial fibrillation.

Firstly, atrial fibrillation is associated with increased risk of stroke. The chaotic heart rhythm and absence of atrial contraction may cause blood to pool in the left atrium and form blood clots. These clots can dislodge and travel with the arterial blood stream to the brain or other organs.

Therefore assessment of stroke risk is important, and blood thinning medications (antithrombotic drugs) should be administered when indicated.

Secondly, the rhythm disturbance itself has to be dealt with. There are two options. The first is to strive to restore sinus rhythm; the second is to accept that atrial fibrillation has become permanent and aim treatment at maintaining acceptable heart rate. The former approach is often termed “rhythm control” while the latter approach is called “rate control”.

Blood Thinning Treatment (Antithrombotic Therapy) in AFib

Every patient with atrial fibrillation should be evaluated for the need of antithrombotic therapy. This is usually based on the CHADS2 risk score or the CHA2DS2-VASc score. These scores address risk factors such as age, gender, history of hypertension or vascular disease, heart failure, and diabetes.

Patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of zero usually don’t need antithrombotic therapy. Those with a score of one should be considered for treatment, and those with a score of two or more should be treated with antithrombotic drugs, unless there are contraindications such as high bleeding risk.

For many years, warfarin has been the most used drug to reduce the risk of stroke in people with atrial fibrillation. Regular blood samples for measurements of INR (International Normalized Ratio) are required for proper dosing of the drug.

Today, several newer medications that don’t require monitoring are available. Examples are dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis).

All these drugs increase the risk of bleeding.

Rhythm Control in AFib

Rhythm control describes a treatment strategy that aims at restoring and maintaining sinus rhythm.

The word “cardioversion” describes the process of converting an arrhythmia to normal sinus rhythm.

Electrical conversion is the most commonly used method to restore sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation. It is a brief procedure, usually performed under general anesthesia or sedation where an electrical shock is delivered to the heart through paddles placed on the chest.

Sometimes, cardioversion may be achieved by drug treatment.

Before cardioversion, antithrombotic treatment is recommended for several weeks to reduce the risk of blood clots. This therapy is usually continued for at least four weeks after cardioversion unless the episode of atrial fibrillation has lasted less than 48 hours.

Once sinus rhythm is restored, antiarrhythmic drug therapy may be needed to maintain sinus rhythm. Examples of drugs used for this purpose are flecainide (Tambocor), propafenone (Rythmol), amiodarone (Cordarone, Pacerone) and dofetilide (Tikosyn).

Rate Control in AFib

Although there are exceptions, most people with atrial fibrillation have fast heartbeats that may eventually exhaust the heart muscle and lead to heart failure. Therefore, control of heart rate is of key importance when treating this arrhythmia.

In many patients, maintaining sinus rhythm may be a difficult task. In these cases, accepting that atrial fibrillation has become permanent may be a better option than continuing to strive for maintenance of sinus rhythm.

Heart rate slowing drugs are used to control heart rate. Examples of such drugs are beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and digoxin.

Studies have suggested that rhythm control and rate control strategies are associated with similar risks of mortality and complications such as stroke. The rhythm control strategy is more often used for younger patients and if symptoms are severe.

Catheter and Surgical Procedures

Maintaining sinus rhythm may sometimes be a difficult task. Accepting a rate control strategy may also be problematic if the patient is very symptomatic. In those cases, catheter ablation or surgical procedures may be an option.

Catheter Ablation for AFib

In this procedure, long thin tubes (catheters) are inserted, usually into the groin and guided through a vein to the heart. Special techniques are used to map out the area or “hot spots” that trigger the arrhythmia. These are usually located in the left atrium, close to the origins of the pulmonary veins. By using radiofrequency energy through electrodes at the catheter tips to induce scarring, the abnormal electric signals may be blocked.

Surgical Procedures

The maze procedure has been used to treat atrial fibrillation. It is performed during open heart surgery by creating several incisions in the atria. This leads to the formation of scar tissue that may help block the abnormal electrical signal causing the atrial fibrillation.

Lifestyle and AFib

Smoking and a sedentary lifestyle are known risk factors for heart disease.

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (6).

A recent study found that general weight management reduced the burden of atrial fibrillation in overweight and obese patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation (7). Therefore, maintaining a healthy weight is important.

Not smoking is of key importance.

Regular physical exercise is associated with lower incidence of atrial fibrillation (8).

A diet low in salt and rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains may be beneficial if high blood pressure is present (9)

Excessive alcohol intake is associated with increased risk of atrial fibrillation (10).

Atrial Flutter

Atrial flutter is an arrhythmia with many similar characteristics as atrial fibrillation, but they differ somewhat with regards to underlying mechanisms and management. Both arrhythmias are associated with increased risk of blood clotting. Some patients have both atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter.

Atrial flutter is not as common as atrial fibrillation. The use of anti-thrombotic, antiarrhythmic and heart rate slowing drugs is similar for atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation.

Electrical cardioversion is often used to restore sinus rhythm in atrial flutter, and catheter ablation may be useful.

The Take-Home Message

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia needing medical attention. It is associated with increased risk of stroke.

Atrial fibrillation is an independent risk factor for mortality in both men and women (11). However, many specialists believe that the atrial fibrillation itself is not causal. In other words, the increased risk of mortality may be due to other factors associated with the arrhythmia, such as high blood pressure and coronary heart disease.

Many patients with atrial fibrillation need long-term treatment with blood thinners (antithrombotic therapy) to reduce the risk of stroke.

Electrical cardioversion is often used to restore normal heart rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Further treatment aims at maintaining sinus rhythm and/or controlling heart rate if atrial fibrillation is persistent. Antiarrhythmic drugs and drugs that slow heart rate are usually administered for this purpose.

Catheter ablation or surgical therapy is reserved for highly symptomatic patients who don’t respond to other types of therapy.

Lifestyle factors such as regular exercise, not smoking, healthy diet and maintaining a healthy weight are all important therapeutic measures.

Very nicely done. Comprehensive AND understandable by lay-people.

I was (obliquely) involved in early research for AFib rate control using amiodarone. I wish I’d been able to do as well a job explaining the background and current practice as you’ve done here.

Thank you very much.

Thanks for the article. My brother has this, and he’s only 68.Non-smoker, athlete, normal weight, and no excessive alcohol. He is not doing well. They can’t do an ablation at present because he has a large clot in his atrium. And he is developing CHF. I really appreciate all your articles that help explain.

Thanks Katy. Appreciate your interest.

Sorry to hear about your brother. My best wishes for him.

Thank you for the excellent article. I was directed to your site by Richard Morris, from the 2KetoDudes podcast. I serve as an admin on his team at the KetogenicForums (https://www.ketogenicforums.com/).

After suffering a back injury in my late 20’s, I managed to gain weight to the point where I weighed somewhere between 550 and 600 pounds. I’ll never know my exact weight because I didn’t go to doctors (long story), and couldn’t find a scale to weigh with. In or around 2007, I started having knee problems due to my weight, and started dieting with a straight Atkins diet. I managed to lose enough that by late 2010, I could weigh on my scales which went up to 500 pounds. When I reached 450 pounds around April of 2011, I added in bicycling, and started riding bicycle. I managed to ride 23,500 between then and now. 2 Years and 2 months ago, I discovered the Low Carb Moderate Protein High Fat diet listening to a Jimmy Moore podcast. Up until then, I had tried many other things including Calorie Counting. I’ve been in Nutritional Ketosis for about 2 years now, and I currently weigh around 270 pounds. For my height, I need to lose between 70 and 90 more pounds, which should be no problem. I’ve also experimented a ton with various forms of fasting; the longest which was 21 days (protein sparing). I’ve also ordered many of my on lipid panels and have 2 years of Blood Glucose and Blood Ketone readings. Fortunately, most of my lipids are very normal and within good ranges.

On December 23rd, 2016, I contracted pneumonia for about the 20th time in my life. It took me about 2 weeks to get over the pneumonia. About 1 week after that, I rode my bicycle for the first time in three weeks and that is when I discovered I had a possible Atrial Fib. Since I have 5 years of heart rate data while riding, I was pretty confident something was wrong. I couldn’t keep my heart rate below 160, at a moderate pace. I have no other symptoms, other than I’ll notice a little fluttering when I go over 200 for my heart rate, and I get more tired more easily. Other than that, I have no symptoms. But, upon learning this and having some family experience with cardiologist with my mother (WPW and Atrial Fib), I started gathering data. I’ve worn a heart rate belt, and have tracked my heart rate for about 4 weeks now. I’ve also purchased an AliveCor Kardia (https://www.alivecor.com/en/) and learned the basics of reading EKG’s. Probably learned more about the heart than I’ve ever thought I would need too. I’m pretty confident I have an Atrial Fib in one or both of the top two chambers, but I have no official diagnosis.

I’m terrified of most doctors after serving as a Quality Assurance coordinator in a hospital setting for 3.5 years. Also, most cardiologists seem to despise the Ketogenic diet, so I’m reluctant to go to them to seek treatment.

My symptoms continue to improve and my resting heart rate is now down in the 80’s and 90’s; not perfect but much better than the 150’s where I started. However, given the time that has expired, I’m starting too wonder if the Atrial Fib will go away on it’s own. I’ve also had 3 rounds of blood lipids done since I had pneumonia and my Trigs are back down to .45 and my hsCRP is back down to .65. So, my inflammation markers seem good.

So, I have to following questions. I hope you can answer them, but will understand if you can’t:

1) Do you know any Keto friendly cardiologists in the US?

2) If not, can I fly over to Iceland for treatment? If so, what can I expect cash costs to be? I don’t carry health insurance.

3) Is fasting a problem with this? I like fasting, but don’t want to resume fasting if it would be problematic. I suspect it would help, but I haven’t fasted more than 40 hours since it occurred, because I worry about possible damage to the heart muscle.

4) I assume staying LCHF is not a problem. Is it?

5) I’ve resumed riding, but try to keep my heart rate as low as possible. Normally, I”ll average about 160. Today, however, I averaged 184 for 1.5 hours of riding and never felt symptoms. Should I quit riding until treated?

Thank you for any assistance you may provide.

Sincerely,

Tom Seest

Dear Tom

Thanks for your comment and interest in my blog.

I would assume any cardiologist in the US will be able to help you with your Afib.

Of course there are many Keto friendly doctors in the US and several obesity experts use a low-carb approach to treat their patients. Dr. Erik Westman, Director of the Duke Lifestyle Medicine Clinic, is a good example.

Staying LCHF is not a problem if you have Afib and fating is not a problem.

Wish you the best of luck.

Largest website to download free Cardiology books easily, please visit the website https://arslanlibrary.com/category/cardiology/