Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Recently, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and other Western countries. The prevalence of the disorder is estimated to be as high as 30% in the general population (1).

With obesity being a major risk factor and due to the aging of the population, the burden of this disorder is expected to rise further.

NAFLD is characterized by fatty deposits in the liver. Patients with NAFLD have an increased risk of cirrhosis, a chronic irreversible scarring of liver tissue.

Having fat in the liver is normal. However, if more than 5-10 percent of the weight of the liver is composed of fat, fatty liver disease may be present.

Steatosis is a term that is used to describe the abnormal retention of fat within cells. Fatty liver or hepatic steatosis describes the abnormal accumulation of fat in the liver.

NAFLD refers to the presence of hepatic steatosis if no other causes of fat accumulation in the liver can be found. Among other important causes that have to be excluded is excessive alcohol consumption.

NAFLD is sometimes associated with inflammation of the liver. If inflammation is documented, the term nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is used to describe the disorder.

Within the NAFLD spectrum, the risk of cirrhosis is primarily associated with the presence of NASH. NASH may progress to cirrhosis in up to 20 percent of cases (2) and is now recognized as an important cause of cirrhosis (3).

Epidemiology of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Data from the United States show that the prevalence of NAFLD has increased steadily during the last 25-30 years, along with the prevalence of central obesity, type 2 diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome (4).

The reported prevalence of NAFLD is from 10 to 46 percent (5,6,7). Studies that have relied on the analysis of tissue samples (biopsy) have reported a prevalence of NASH between 3 to 5 percent.

Most patients are diagnosed with NAFLD in their 40s or 50s (8). Some studies report a higher prevalence in men while some suggest the disorder is more common among women.

NAFLD is strongly associated with the presence of the metabolic syndrome. Patients with NAFLD, particularly those with NASH, usually have one or more of the following; obesity (central obesity in particular) high blood pressure (hypertension), lipid disorders, insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes.

NAFLD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Although this may be due to its association with other components of the metabolic syndrome, one study has suggested that NAFLD may be independently associated with cardiovascular disease (9).

One study has suggested that NAFLD is more frequent among patients who have had their gallbladder surgically removed (10). The authors of the paper suggested that surgical removal of the gallbladder may itself be a risk factor for NAFLD.

Other conditions associated with NAFLD include polycystic ovary syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea.

The Underlying Mechanisms of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

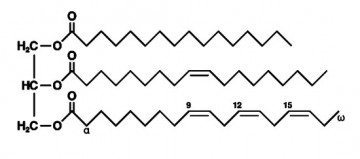

It is primarily triglycerides that accumulate in the liver in patients with NAFLD.

Triglyceride accumulation may be due to an excessive importation of free fatty acids to the liver from adipose (fat) tissue.

Excessive amounts of fatty acids may also be produced by the liver cells themselves due to an increased conversion of carbohydrates and proteins to triglycerides. Furthermore, beta-oxidation of free fatty acids in the liver may be impaired leading to accumulation of fatty acids.

Defective transport of fatty acids from the liver may also contribute to the accumulation of triglycerides in the liver. This may be due to reduced availability of VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein), the main carrier protein for triglycerides.

The Role of Insulin Resistance in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Although the underlying mechanisms have not been clearly defined, it is believed that insulin resistance plays a key underlying role in most patients with NAFLD and NASH (11,12).

Obesity and type 2 diabetes, conditions frequently associated with NAFLD, are both associated with insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance affects lipid metabolism in several ways, For example, insulin resistance is associated with increased triglyceride synthesis (13) and enhanced uptake of free fatty acids by liver cells. Each of these may contribute to the accumulation of triglycerides in the liver (14).

Although NAFLD is most often associated with insulin resistance, it is believed that a second defect resulting in injury to liver cells has to be present as well. Several potential oxidative stressors have been proposed. These may deplete necessary enzymes such as glutathione, vitamin E, beta-carotene and vitamin C, making the liver susceptible to injury.

Several hormones derived from adipose tissue, such as adiponectin, leptin, and resistin, may play a significant role in NAFLD, partly through their modulating effect on insulin resistance.

A recent study found that regular sugar-sweetened beverage consumption was associated with greater risk of fatty liver disease, particularly in overweight and obese individuals, whereas diet soda intake was not associated with measures of fatty liver disease (15).

The Role of Fructose – Is It the Silent ‘Sweet Killer’?

Several studies have shown that the metabolic effects of fructose consumption may predispose to fat accumulation in the liver.

For the last few decades, we have seen an enormous rise in fructose consumption. Today, fructose is massively used in the food industry due to its sweeter taste and lack of inhibition of satiety compared with other types of sugar (16).

There is strong evidence from both experimental and animal studies suggesting that high fructose consumption can lead to insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and lipid abnormalities, all of which appear to be underlying mechanisms involved in NAFLD

The metabolic effects of fructose are very different from those of glucose. The entry of fructose into cells is not dependent on insulin and does not promote insulin secretion, unlike glucose.

Although fructose feeding in the short term does not significantly increase insulin secretion, long-term administration can cause insulin levels to rise (17)

Fructose may predispose to NAFLD by promoting an increase in blood levels of triglycerides (18). Experimental studies have shown that elevated triglycerides caused by excessive fructose intake may be a precursor of insulin resistance (19).

Fructose-sweetened beverage consumption habits are associated with a central fat distribution (20), a known risk factor for NAFLD.

Symptoms, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis

Most patients with NAFLD don’t have any symptoms. However, some patients with NASH complain of fatigue and vague discomfort in the upper right area of the abdomen.

Usually, patients with NAFLD come to attention because of elevated liver transaminases revealed by blood sample or because fatty infiltration of the liver is incidentally detected on ultrasound or radiographic examination such as computed tomography (CT) scanning.

Sometimes an enlarged liver may be discovered during physical examination.

Blood Tests and Radiographic Findings

Patients with NAFLD often have mild or moderate elevations of serum transaminases, alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST). However, normal levels don’t exclude NAFLD.

The degree of transaminase elevation does not necessarily reflect the severity of the disease (21).

Blood levels of alkaline phosphatase may become elevated in NAFLD. Sometimes ferritin level is elevated as well.

Increased echogenicity on ultrasound, decreased liver attenuation on CT, and an increased fat signal on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may suggest NAFLD.

Patients with NAFLD typically have elevated triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio.

Diagnosis

To diagnose NAFLD, signs of steatosis have to be revealed by imaging techniques or biopsy, significant alcohol consumption has to be excluded, and other causes of fatty liver disease have to be ruled out (22).

A thorough history is important to exclude other potential causes of fatty liver disease such as alcohol use, drugs or medication use. Viral hepatitis may have to be excluded as well.

Usually, the clinical picture, blood tests, and imaging techniques will suffice to diagnose NAFLD.

The majority of patients don’t need to have a tissue sample taken by biopsy. However, a biopsy is the only method that can differentiate NAFLD from NASH.

Assessment of Disease Activity

A validated NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) can be used grade disease activity in patients with NAFLD (23). The score is based on a summation of scores for specific signs of inflammation and scarring in a tissue sample. A score > 5 corresponds to NASH.

Another score, the NAFLD Activity Score is based on the patient’s age, body mass index, blood sugar levels, transaminase levels, platelet count and serum albumin.

Natural History and Prognosis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Patients with NAFLD are at risk of progressing to NASH and eventually develop liver cirrhosis, a disorder that may progress to end-stage liver disease.

The likelihood of liver disease progression increases if the biopsy reveals signs of inflammation. Other factors associated with risk are older age, the presence of diabetes, elevated transaminases, high body mass index and signs of visceral adiposity, taking into account waist circumference, body mass index, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol.

The risk of liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) is increased, but only among patients with NAFLD who progress to cirrhosis (24).

Patients with NAFLD have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Although mortality due to liver-related disease is increased (25), cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death among patients with NAFLD.

Whether patients with NAFLD have an increased risk of mortality is unclear. Some studies indicate that mortality is increased (26) while others don’t (27).

Management of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Weight loss is the only therapy for patients with NAFLD and NASH that has been proven to be effective and safe.

Several studies suggest that weight loss is beneficial in patients with NAFLD (28,29). However, some studies suggest that rapid weight loss should be avoided (30)

A 2012 meta-analysis suggests that physical exercise, with or without weight loss may be beneficial (31).

Treating risk factors for cardiovascular disease is important. This includes treatment of diabetes, lipid disorders, and high blood pressure.

Alcohol intake should be avoided. Heavy alcohol use is associated with risk of disease progression. Whether light or moderate alcohol consumption is harmful is not entirely clear.

A meta-analysis published 2012 showed that treatment with omega-3 fatty acids was associated with improvement in hepatic steatosis and liver transaminases (32).

Although numerous drugs have been tested for NAFLD and NASH, pharmacological treatment hasn’t been proved to be beneficial. However, vitamin E is sometimes administered. A randomized study published 2010 showed a beneficial effect of vitamin E in patients without diabetes with improvement in liver transaminases and less hepatic steatosis (33). However, these results have not been confirmed by other studies.

Hopefully, future studies will reveal the role of fructose intake in NAFLD and whether avoiding fructose is beneficial.

The management of patients with NAFLD who develop cirrhosis is similar to that for cirrhosis due to other causes. It includes management of portal hypertension, regular screening for signs of liver cancer, and consideration of liver transplantation in severe cases.

The Take-Home Message

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the leading cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and other Western countries.

Patients with NAFLD have an increased risk of cirrhosis, a chronic irreversible scarring of liver tissue.

If inflammation is documented, the term nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is used to describe the disease.

Central obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, lipid abnormalities and high blood pressure are conditions often associated with NAFLD.

Patients with NAFLD have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Weight loss is the only therapy for patients with NAFLD and NASH that has been proven to be effective and safe.

Discover more from Doc's Opinion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This BMJ rapid response comment is by Dr. William T Neville: “The article fails to mention the main causes and most effective treatments for NALFD. This is not surprising because, although well researched, these causes and treatments are not well known. Consumption of vegetable oil, containing omega-6 fatty acids such as linoleic acid, is the most effective way of inducing fatty liver disease. Saturated fats reverse NAFLD and beef fat does this most effectively. Sugar, particularly fructose, also causes NAFLD. Omega-3 fats and medium chain triglycerides are beneficial.” https://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g4596/rr/762078

Eleonora Scorletti & Christopher Byrne: “Typically, with a Westernized diet, long-chain omega-6 fatty acid consumption is markedly greater than omega-3 fatty acid consumption. The potential consequences of an alteration in the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acid consumption are increased production of proinflammatory arachidonic acid-derived eicosanoids and impaired regulation of hepatic and adipose function, predisposing to NAFLD.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23862644

Frances Sladek: “The incidence of obesity in the U.S. has increased from 15% to 35% in the last 40 years and is expected to rise to 42% by 2030. Paralleling this increase in obesity are a number of dietary changes, most pronounced of which is a >1000 fold increase in consumption of soybean oil from 0.01 to11.6 kg/yr/capita from 1909-1999: soybean oil consists of 50-60% linoleic acid (LA), so the energy intake from LA has increased from 2% to >7%/day. LA is an essential fatty acid and a precursor to arachidonic acid, which is linked to inflammation, a key player in obesity, diabetes, cancer, etc. Another component of the American diet that has increased substantially in the last four decades is fructose, primarily in the form of high fructose corn syrup in processed foods and sodas. The roles of both LA and fructose in the current obesity epidemic are under intense scrutiny but are not well understood and seldom compared side-by-side.” https://press.endocrine.org/doi/abs/10.1210/endo-meetings.2013.OABA.9.SAT-708

Ramón Rodrigo: “Human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) associated with obesity is characterized by depletion of hepatic n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), with lower LCPUFA product/precursor ratios and higher 18:1n-9 trans levels in adipose tissue, both in patients with steatosis and in those with steatohepatitis.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15454290

Do we know what causes NAFLD? Perhaps not. Why? Because nobody seems interested in doing a trial involving reduced linoleic acid intake. ” The debate concluded with agreement by all that we need a randomized controlled trial to compare the effect of low and high intakes of LA. The trial should have typical US intakes of omega-3 PUFAs, with 7.5% energy from LA (the current US intake) in one group and 2.0% LA (historical intake) in the other.” https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/324749

Thanks David. Appreciate your thoughts. Obviously, when it comes to omega-6 the jury is still out.

There’s two kinds of proof: legal and scientific. In the jury system, for obvious reasons, consensus may be required to establish guilt or innocence. In science, however, when a matter is controversial because it is poorly understood, forcing a scientific consensus creates confusion and impairs our ability to accurately explain how the real world works.

In a 2003 speech delivered at the California Institute of Technology the late Michael Crichton said, “Historically, the claim of consensus has been the first refuge of scoundrels; it is a way to avoid debate by claiming that the matter is already settled. Whenever you hear the consensus of scientists agrees on something or other, reach for your wallet, because you’re being had. Let’s be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results. The greatest scientists in history are great precisely because they broke with the consensus. There is no such thing as consensus science.”

If it’s consensus, it isn’t science. If it’s science, it isn’t consensus. Period.” https://creation.com/crichton-on-scientific-consensus

Excerpt from a report regarding an experiment comparing the effects of saturated and unsaturated fats on, among other things, liver fat. “Deol and the rest of the research team found to their surprise that the

parallel diet containing GM soybean oil induced weight gain and fatty

liver essentially identical to that of a diet with regular soybean oil,

with the exception that the mice remained insulin sensitive and had

somewhat less adipose (fat) tissue.” https://ucrtoday.ucr.edu/27507

I’ve been finding it useful to Google the names of scientists in conjunction with linoleic acid to ascertain their interest in linoleic acid research. For example, Google – Nina Teicholz linoleic acid

Axel —

Another interesting post. Thank you! I have some thoughts to share, if you don’t mind.

Now that dietary cholesterol has been found “not guilty” by everyone (even in the US), it’s worth noting that the bad advice started with a reasonable assumption: Since high blood cholesterol is strongly correlated with heart disease, then eating less cholesterol might lower blood cholesterol levels and the risk of heart disease.

Decades later, we now realize it’s not that simple. What we eat can have a big effect on our blood cholesterol level, but it’s not the cholesterol content of the food that causes the problem (or even the cholesterol level in the blood). At least not for most of us.

Since NAFLD (and perhaps AFLD) are characterized by the storage of too much fat (too many triglycerides) in the liver, then wouldn’t a reasonable assumption be that reducing triglycerides would help?

I’m just a sample of one, but I think my path was a common one. When I was younger and more active (including a few triathlons), eating a low-fat, high-carb diet was fine. But when I was in my 50’s and less active, I was overweight, had metabolic syndrome, was on the path toward T2 diabetes, and starting to get NAFLD. (My fasting triglycerides were quite high, in a natural state.)

Then I went on a low-carb, high-fat diet. Same exercise level. Dropped 30+ pounds, down to a normal BMI. Stopped the statin, niacin and BP meds because I no longer needed them. My HDL is now way up. My trigs are way down. My LDL-C is up a bit (but I’m not worried about that). And I have no signs of metabolic syndrome or NAFLD.

Did I cure my NAFLD because I lost weight or cut carbs? Or both? I don’t know for sure, but I believe it’s all related. (There’s no reason to think these things are not related.)

I don’t know for sure that cutting carbs would help NAFLD and AFLD for most patients, but since high triglyceride levels come from a carb-rich diet, I suspect that cutting carbs is a reasonable place to start.

Richard

Thanks Richard.

I agree with you that lowering triglycerides will probably be helpful. Usually that can be achieved by carbohydrate restriction as you suggest. There are studies showing positive metabolic effects of low-carb diets and they seem to reduce the lipid content of the liver.

However, as you said, it may be difficult to decide whether it’s the effect of weight reduction or some other metabolic effects of carbohydrate restriction per se that affect the fat content of the liver.

For example, one randomized study found that a prolonged hypocaloric diet low in carbohydrates and high in fat had the same beneficial effects on intrahepatic lipid accumulation as the traditional low-fat hypocaloric diet. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21400557

Interesting stuff. Anecdotally, I’ve heard varying opinions (based on BG levels) of exactly what frutcose SEEMS to be doing, or not doing, to any given individual’s body. I’ll be keeping an eye on this research. Mel at fattyliverdietguide.org