Estimated reading time: 21 minutes

A forgotten folder. A cryptic label. And a quiet set of instructions that may have rewritten the rules of modern medicine. This story doesn’t start with a discovery—it begins with a cover-up. Not in a lab or at a press conference, but deep in the shadows, in an archive no one was supposed to search. And it begins with a question that still unsettles:

What if the science we trusted wasn’t just flawed, but carefully steered?

Prologue: The File That Shouldn’t Exist

The air in the basement archives was stale, tinged with the musty scent of aging paper and timeworn glue. Overhead, fluorescent lights flickered with a faint hum, casting uneven shadows across rows of steel shelving

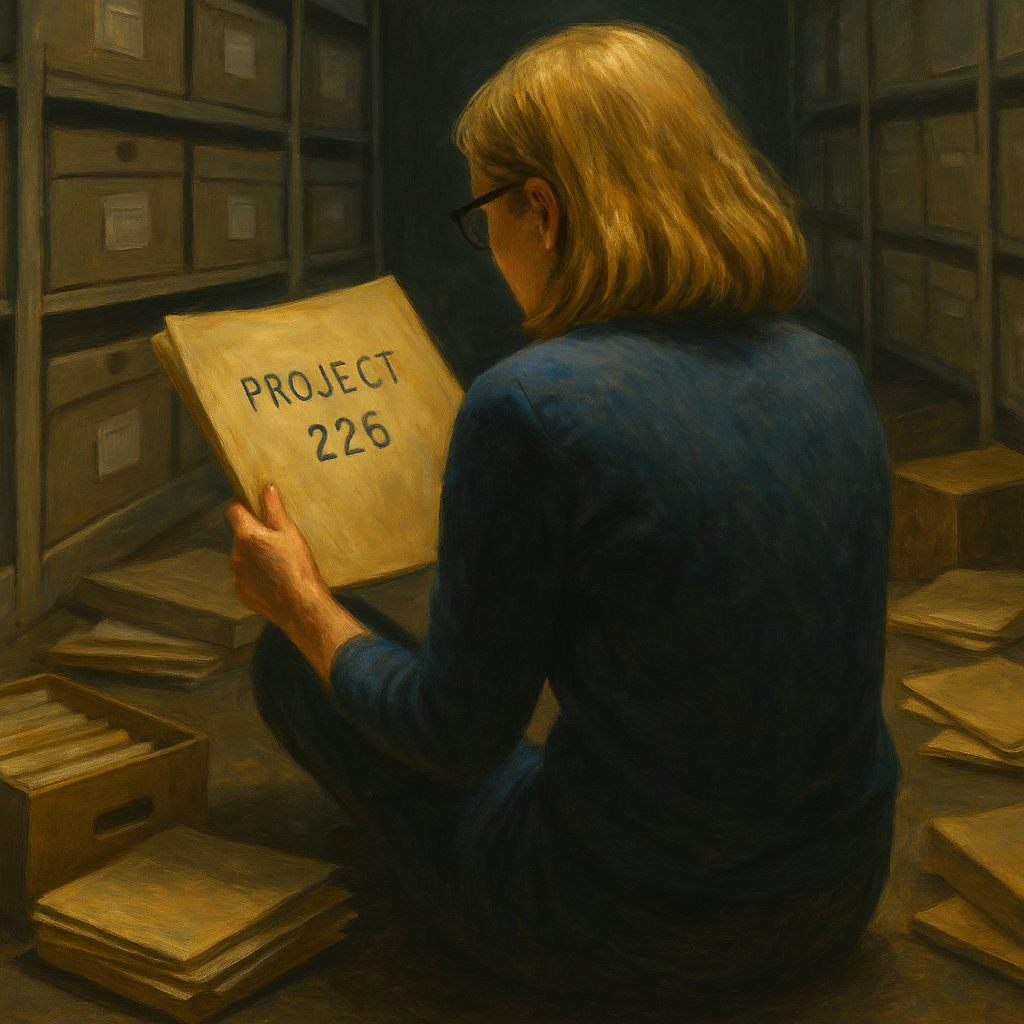

Cristin Kearns, a former dentist turned public health detective, crouched beside a stack of unmarked boxes. She was deep in the Countway Library at Harvard Medical School, immersed in the archived papers of Dr. Mark Hegsted—a Harvard nutritionist whose work in the 1960s had become quietly influential.

She was on a mission to uncover what she suspected was a buried story—one she hoped to bring into the light. The silence was dense, broken only by the soft rustle of her latex-gloved fingers flipping through brittle folders.

She was tired. Her legs ached from hours of searching. So far, most of what she’d uncovered had been mundane—meeting agendas, outdated nutritional reports, dead-end correspondence. Still, she pressed on. The sugar industry had secrets. And she had come to find them.

Then she saw it.

A plain manila folder nestled between budget reports and scientific abstracts. Faint graphite letters etched across its top: “Project 226.”

She hesitated. Her breath caught.

Sliding the folder onto her lap, she gently pried it open. The scent intensified—old tobacco, copier ink, something almost metallic. Inside: memos typed on crisp letterhead, margin notes in fountain pen, a ledger entry that read simply: “$6,500 to Harvard University.”

She read. Then reread.

The names jumped out at her like ghosts—Mark Hegsted. Fred Stare. The New England Journal of Medicine.

One memo outlined edits to a manuscript before submission. Another encouraged emphasizing dietary fat over sugar in the conclusions.

Cristin’s heart pounded. Her mouth went dry.

This wasn’t an academic exchange. This was choreography—a deliberate rewriting of science.

She wasn’t just holding research. She held the pivot point of a public health story we thought we understood.

What it contained wasn’t just a trail of memos and payments. It was a quiet but undeniable sign that the story of heart disease in America had been nudged, not by new discoveries, but by deliberate influence. It raised a question that still echoes today: What happens when the evidence we trust has been curated for us?

Chapter 1: Buried in the Basement

The folder had cracked open a secret. But to understand its meaning, we have to rewind—nearly sixty years back in time—to a moment when the science of nutrition teetered between two futures.

By the mid-1960s, the American public had grown anxious. Heart attacks were claiming fathers, uncles, and neighbors. An invisible threat was eroding the sense of control that postwar prosperity had promised.

Doctors had data, cholesterol measurements, autopsy reports, and growing epidemiological maps. But causation remained elusive, and the search for a unifying theory created a vacuum. And in that vacuum, certain personalities rose.

Ancel Keys didn’t just fill the void. He dominated it. A towering figure in both intellect and will, Keys had the rare ability to turn data into dogma. At conferences, he challenged anyone who dared suggest an alternate explanation. He was combative, yes—but also compelling. His Seven Countries Study offered what many craved: order. A graph here, a mortality curve there, and suddenly it all made sense: the more saturated fat a nation ate, the more heart disease it suffered.

But not everyone bought it. Behind the headlines and public declarations, the scientific community was far from unified.

Biochemists were raising questions about carbohydrate metabolism. Early metabolic ward studies were beginning to show that sugar—not fat—could spike triglycerides. Lipidologists debated the role of VLDL and remnant particles. A few pathologists noted that fatty streaks in arteries did not always correlate with dietary cholesterol.

And then there was Dr. Pete Ahrens at Rockefeller University, a lipid pioneer who urged caution. “It’s not just about cholesterol,” he warned. “The body’s response to different macronutrients is complex, and reductionism may betray us.”

But moderation made for poor headlines.

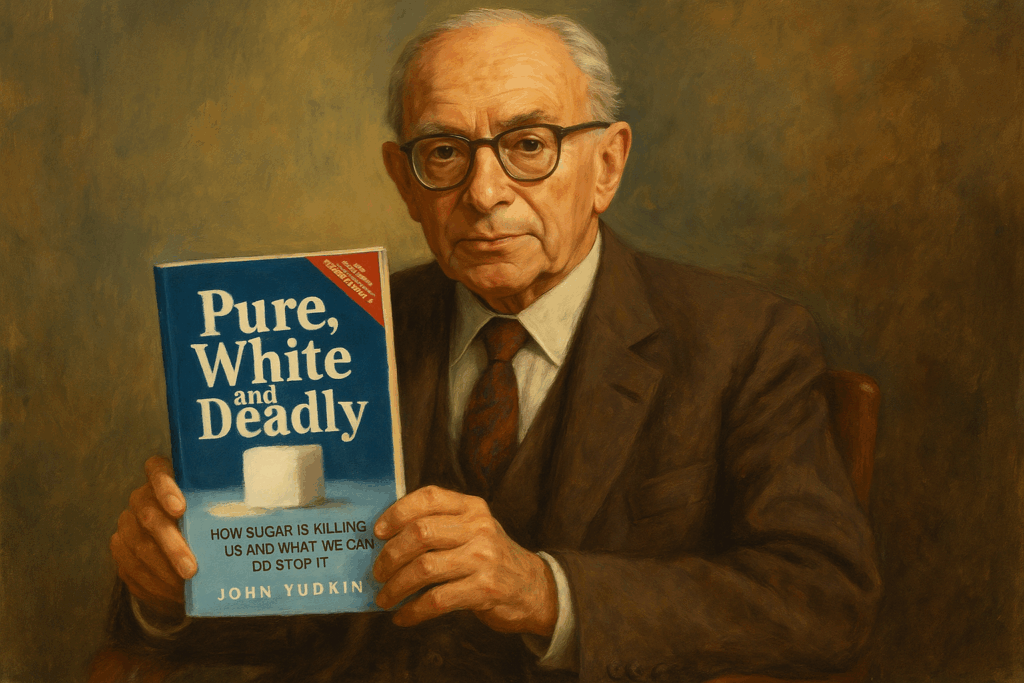

Across the Atlantic, a quieter but no less rigorous mind drew different conclusions. Dr. John Yudkin, a British physiologist and nutritionist, had been studying another ingredient that flooded the postwar diet: sugar. He didn’t have Keys’ charisma, nor his political acumen. But he had data—and concern.

In 1972, Yudkin published Pure, White and Deadly, a startling critique of sugar and its hidden role in disease. He pointed to laboratory studies showing sucrose raised triglycerides and promoted insulin resistance. He noted that the rise in sugar consumption tracked not with fat, but with rising heart disease and obesity rates.

Sugar, he argued, wasn’t just empty calories. It was a biochemical saboteur.

He was met with a wall of silence. And then, a storm of ridicule.

The dietary debate was no longer just academic. It was personal. Political. And profitable. He was ignored. Or worse, dismissed as fringe.

Behind closed doors, others took notice—especially the people who had the most to lose.

Chapter-2: The Quiet Meeting

The sugar industry had been watching. And when the science began to shift against them, they didn’t panic. They planned.

Somewhere behind the boardroom doors of mid-century Manhattan, the sugar industry decided not to fight the science, but to guide it.

A confidential memo had circulated just days before, rattling even the most confident executives. Findings from university labs in the US and abroad pointed to a new culprit: sugar. Not fat. Not cholesterol. But refined carbohydrates that spiked triglycerides, raised insulin, and possibly contributed directly to atherosclerosis.

Momentum was building. On July 11, 1965, the New York Herald Tribune ran a full-page article on new sugar studies published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. It warned that emerging research “threatened to tie the whole business [of diet and heart disease] in a knot.” What had once seemed speculative was gaining traction: sugar’s role in heart disease was no longer a fringe hypothesis—it was becoming credible. The industry knew it needed to act.

Around a smoky table, ties loosened and tension high, one executive reportedly said, “It’s just one paper.”

“For now,” came the reply.

They knew what was at stake: billions of dollars, thousands of jobs, and the carefully cultivated image of sugar as innocent and pure.

Then one voice cut through the haze:

“We don’t need to fight the science. We just need to guide it.”

No one argued.

The plan was quiet, strategic—not a press release or an ad campaign, but a scientific intervention. They would channel their efforts into the journals. Into the very institutions that shaped consensus. At the helm was John Hickson, Vice President and Director of Research at the Sugar Research Foundation (SRF)—a polished operator who understood that shaping science meant shaping belief.

A list of potential allies quickly converged on Harvard. At the center was Dr. Mark Hegsted—well-published, respected, and, as they hoped, receptive. His department chair, Dr. Fred Stare, brought institutional clout. Together with Dr. Robert McGandy, they agreed to write a two-part literature review for what would amount to over $50,000 in today’s dollars.

The funding? Quiet.

The edits? Subtle.

The goal? Crystal clear.

Project 226 was born—a masterstroke of public relations disguised as scholarship. The authors’ academic credentials gave the papers enormous weight. But the sugar industry’s role in shaping them would remain entirely hidden.

On July 30, 1965, SRF executive John Hickson clarified the Foundation’s expectations in writing to Hegsted:

“Our particular interest had to do with that part of nutrition in which there are claims that carbohydrates in the form of sucrose make an inordinate contribution to the metabolic condition, hitherto ascribed to aberrations called fat metabolism. I will be disappointed if this aspect is drowned out in a cascade of review and general interpretation.”

Translation: “We’re concerned about the growing claims that sugar (specifically sucrose) contributes to metabolic problems like heart disease—problems that the public currently blames on fat. We want to make sure your article pushes back on those sugar-related claims. Don’t get distracted by broader discussion. Focus on defending sugar.”

Hegsted replied with assurance:

“We are well aware of your particular interest in carbohydrate and will cover this as well as we can.”

A simple goal: exonerate sugar. Blame fat.

And make it look like objective science.

The draft would be sent. The edits would follow. And soon, the most trusted medical journal in America would carry their message, without a single word about who had paid for it.

Chapter 3: A Journal’s Quiet Influence

This was the quiet heart of the strategy: to embed the sugar industry’s narrative within the scientific canon. And there was no better vehicle than The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Prestigious, influential, and widely read by physicians and policymakers alike, it offered legitimacy with a stamp of neutrality.

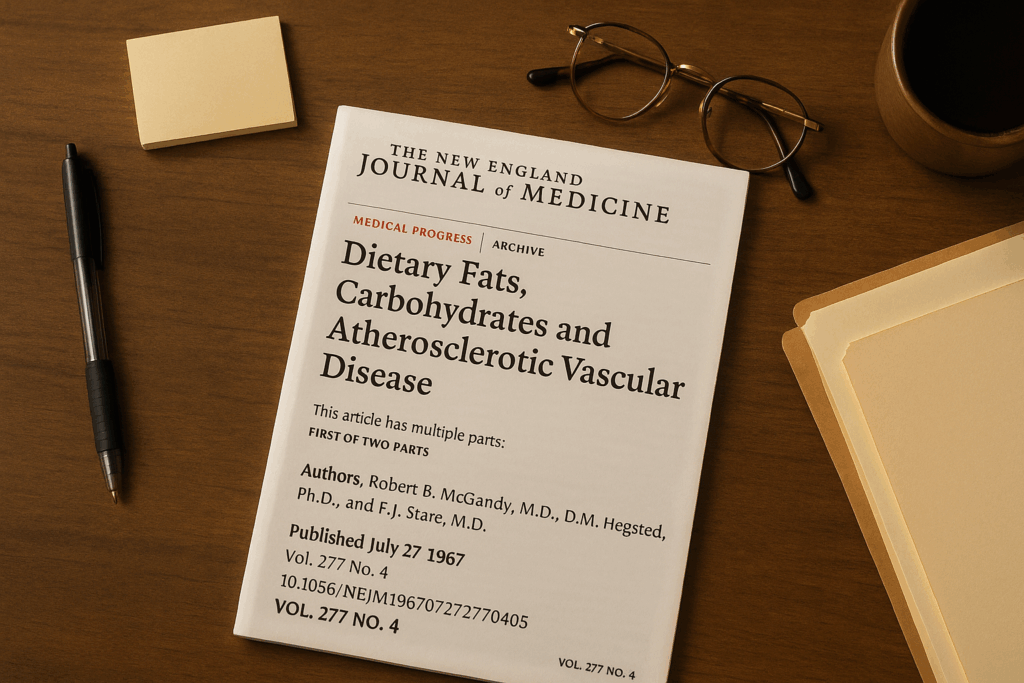

A two-part review article titled Dietary Fats, Carbohydrates and Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease appeared in The NEJM in 1967, published one week apart—on July 27 and August 3.

The review, co-authored by Dr. Mark Hegsted, Dr. Robert McGandy, and Dr. Fred Stare, did precisely what the SRF had paid for. It wasn’t a smear campaign against emerging science on sugar. That would’ve drawn attention. Instead, it was a masterpiece of omission and emphasis.

Written with academic restraint and layered in careful prose, both installments bore all the markings of impartial science. There was no disclosure of funding from the SRF; at the time, such declarations were not required.

Studies linking sugar to elevated triglycerides were downplayed or discredited. The review emphasized dietary fat and cholesterol as the main culprits in coronary heart disease, casting doubt on alternative hypotheses without appearing overtly biased.

One of the reviews stated flatly: “The major evidence today suggests only one avenue by which diet may affect the development of atherosclerosis. This is by influencing the concentration and the composition of serum lipids.” It continued, “The practical dietary changes that are probably most useful in reducing the incidence of atherosclerosis are those which reduce the intake of saturated fat, cholesterol, and total calories.”

Carbohydrates were mentioned, but their role was dismissed: “There can be no doubt that serum cholesterol levels can be substantially modified by the diet. The effect of dietary carbohydrate on serum cholesterol is minimal…”

For many in the nutrition science community, the article became a keystone. It nudged uncertain researchers toward the fat hypothesis and away from carbohydrate critique.

While Robert McGandy was listed first on both articles—typically a marker of lead authorship—it was Hegsted who corresponded with the SRF, shaped the review’s framing, and later became a central figure in US dietary policy. The paper bore three names, but only one would become its lasting symbol.

But the publication timeline may raise some questions. Hickson’s memo to Hegsted was sent in July 1965, yet the articles did not appear until mid-1967. While such delays were not unusual in academic publishing, the correspondence suggests the SRF remained engaged during the review process. Drafts appear to have been reviewed and discussed with input from the foundation. Whether the delay was purely logistical or partly strategic is unclear, but the result was carefully calibrated. Correspondence reveals that drafts were reviewed and edited for tone and emphasis.

Young scientists learned quickly: sugar didn’t get funded. Sugar didn’t get published. Sugar didn’t get applause.

A quiet orthodoxy formed—not declared, but enforced. At its center was a review article that never acknowledged its true author.

But that review didn’t just sit on a shelf. It began to move—in newspapers, boardrooms, and eventually, into the bloodstream of public policy itself.

Chapter 4: The Ripple Effects

Within weeks of its release, wire‑service bulletins and syndicated columns echoed the Harvard authors’ conclusions. While no headlines said it outright, the message was unmistakable: fat was the culprit, and sugar was off the hook.

Morning talk shows invited nutrition experts who amplified the review’s reassuring tone. The American public, already wary of cholesterol, took note—and so did food marketers. Cereal ads boasted “no fat, no cholesterol” while packing spoonfuls of sugar; candy makers ran copy that read: “Quick energy—without the artery‑clogging grease.”

Professional societies followed the shifting tide. The American Heart Association’s 1970 dietary recommendations, citing the growing consensus, urged Americans to limit total and saturated fat. Sugar was mentioned only in passing, as an optional calorie-reducer for those concerned about their weight. By 1974, an AMA Council report used the NEJM review to argue there was “insufficient evidence” that sucrose posed a cardiovascular threat.

The pivot reached Capitol Hill in 1977, when Senator George McGovern’s Select Committee issued “Dietary Goals for the United States.” Saturated fat targets were front‑and‑center; sugar reduction was also advised, but press coverage framed the report almost entirely as a mandate to eat less fat. The committee’s chief scientific adviser later admitted that the Harvard review—and the prestige it carried—had weighed heavily in their deliberations.

Three years later, the first USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans (1980) codified the message: “Avoid too much fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol.” Sugar merited a softer directive: “Use only in moderation.” Food manufacturers responded with an avalanche of “fat‑free” products sweetened to the hilt. Sales soared while national per‑capita sugar intake climbed.

In effect, a single, undisclosed industry‑funded article had migrated from the pages of an elite medical journal into the grocery cart of nearly every American household—and from there into federal policy.

We will never fully know the extent to which these articles influenced individual choices, medical advice, or the direction of public policy. But their impact wasn’t limited to the United States. The same narrative soon shaped official guidelines and marketing campaigns in Europe, Australia, Canada, and other regions, influencing food labeling, health education, and medical curricula worldwide.

The metabolic consequences would take decades to measure, but the narrative was set: fat was the villain, and sugar wore a cloak of innocence.

Chapter 5: Doubt by Design

While the public was learning to fear fat and embrace “heart-healthy” low-fat foods, one voice kept calling out from the margins—softly at first, then more urgently, until it was eventually ignored.

That voice belonged to John Yudkin. By the early 1970s, he had become a vocal critic of refined sugar’s role in heart disease and diabetes. But his concerns—though scientifically grounded—were increasingly dismissed as extreme. His funding disappeared. Speaking invitations dried up. Colleagues distanced themselves.

Yudkin was not alone. A broader scientific discussion was unfolding around sugar’s metabolic impact. Early metabolic ward studies, lipid research, and pathophysiological data were starting to challenge the dominant narrative. But shifting the tide of consensus was not just a scientific matter—it was political.

The Sugar Association responded with strategic clarity. It didn’t need to disprove every critique. It needed to shape the message.

In the mid-1970s, the Association launched the “Sugar in the Diet of Man” campaign. Advertisements promoted sugar as a dietary aid, claiming that candy or a soft drink before meals could actually help reduce appetite and caloric intake. One ad read: “The sugar in a soft drink now can save me a lot of calories later.” Another: “Snack on some candy about an hour before lunch.”

This was more than spin. According to Cristin Kearns and colleagues, the campaign influenced how regulatory bodies, including the FDA, perceived the safety of sugar in the 1970s. By emphasizing lifestyle and appetite control, the campaign reframed sugar as a solution, not a problem.

But messaging was only one front. Internally, the SRF was pursuing a more calculated strategy. Memos from executive John Hickson outlined a plan to shape not only public opinion but the scientific record. He recommended commissioning opinion polls, organizing a symposium to challenge critics before their peers, and funding research on coronary heart disease to replicate and revise studies that implicated sugar as a factor. “Then we can publish the data,” Hickson wrote, “and refute our detractors.”

The tactic wasn’t denial. It was doubt. Deliberate, disciplined, and designed.

This echoed the tobacco industry’s strategy.

As one sugar executive later admitted: “Doubt is our product too.”

Even American scientists like George Mann, who once called the dietary fat hypothesis “the greatest scientific deception of this century,” faced obstacles. Publication became harder. Funding scarcer. Controversy unwelcome.

Whether knowingly or not, universities, journals, and foundations contributed to a professional climate that discouraged dissent. The result was not outright censorship, but a kind of institutional gravity that pulled inquiry in safer directions.

In time, sugar’s critics were marginalized not by argument, but by attrition.

Still, truth has a way of resurfacing—especially when someone opens the wrong box.

Chapter 6: The File That Changed the Past

Half a century later, in the dim basement of an archive, the evidence resurfaced. And the story, long buried, began to unravel.

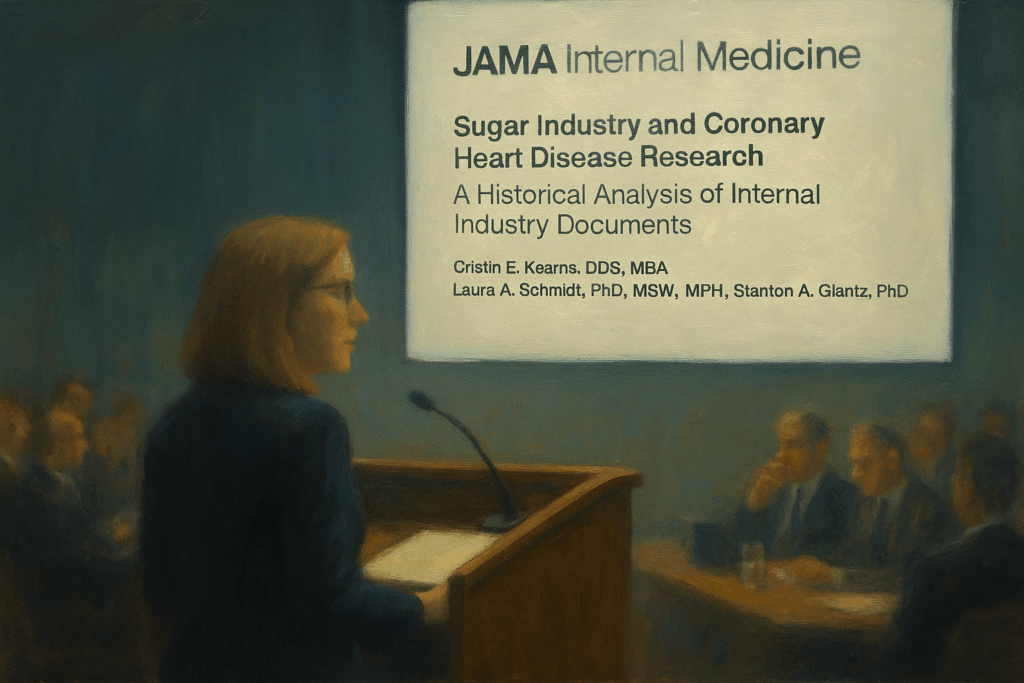

Cristin Kearns knew what she had found. But she also knew how difficult it would be to tell the story.

Together with UCSF colleagues Laura Schmidt and Stanton Glantz, she pieced together the trail: internal SRF documents, payment receipts, correspondence with Harvard faculty, and editorial suggestions that were never disclosed.

In 2016, their findings were published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The researchers examined over 340 documents—spanning 1,582 pages—detailing correspondence between the sugar industry and two key figures: Roger Adams, a professor of organic chemistry who served on industry advisory boards; and D. Mark Hegsted, one of the Harvard scientists behind the pivotal 1967 literature review.

It was a revelation—not just of an old scandal, but of the fragility of science when money speaks louder than evidence.

“As the saying goes, he who pays the piper calls the tune,” remarked Stanton Glantz, senior author of the JAMA Internal Medicine paper. The paper trail made one thing clear: this wasn’t passive sponsorship. It was strategic authorship, with the sugar industry selecting the song, setting the tempo, and quietly conducting from behind the curtain.

Kearns didn’t just uncover a paper trail—she revealed a fracture in the very foundation of how we understand diet and disease. The 1967 NEJM review article, funded through Project 226, not only influenced public policy; it also diverted scientific attention away from key biological mechanisms now central to cardiometabolic health.

Take triglycerides, for example—blood fats long known to rise in response to high sugar intake. Or hepatic de novo lipogenesis—the liver’s conversion of excess fructose into fat, which can drive non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and atherogenic dyslipidemia.

Even in the 1960s, researchers began to piece together how refined carbohydrates, particularly sucrose, could disrupt lipid metabolism and contribute to the development of insulin resistance. These weren’t fringe ideas. They were biologically plausible, clinically relevant, and increasingly inconvenient. Project 226 helped suppress them, not through censorship, but through omission, emphasis, and redirection. And that redirection reshaped not only scientific journals but also federal policy and public trust.

Project 226 had worked. And for fifty years, no one had known.

The Sugar Association issued a carefully worded statement in response to Kearns’ JAMA publication. While it acknowledged that it “should have exercised greater transparency in all of its research activities,” it emphasized that funding disclosures were not customary at the time. The group also pushed back against the study’s implications, criticizing what it called Kearns’ “continued attempts to reframe historical occurrences” to align with “current public sentiment against sugar.”

The tension reflected a broader dilemma: how should we judge past industry influence by today’s standards?

The Sugar Association also expressed concern about the “growing use of headline-baiting articles to trump quality scientific research – we’re disappointed to see a journal of JAMA’s stature drawn into this trend.”

Chapter 7: The Long Echo

What happened in 1967 didn’t stay in 1967.

Unearthing the truth in 2016—nearly half a century later—may have come too late to stop the momentum. Because by then, the consequences had already rippled outward, shaping decades of dietary guidance, scientific consensus, and cultural belief.

To be sure, the field of nutrition science has undergone significant evolution. We now understand that not all fats are created equal, that triglycerides and insulin resistance matter, and that refined carbohydrates are far from harmless. However, early distortions, especially when amplified by institutions, can reverberate for generations, influencing how guidelines are written, how doctors are trained, and how patients perceive risk.

The review published in The NEJM in 1967 didn’t just influence policymakers. It helped tip the scales of public perception. Fat became the enemy. Supermarket aisles filled with low-fat, “heart-healthy” alternatives—many of them brimming with added sugar. Yogurts, salad dressings, and breakfast cereals were reformulated to follow the new gospel.

By the 1980s, the unintended consequences were becoming increasingly apparent. A generation that followed the rules—trading butter for margarine, eggs for cereal—found itself in the crosshairs of rising obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. The pendulum had swung, but not necessarily in the right direction.

And yet, to say it was all wrong would be just as misleading.

There is evidence that efforts to reduce saturated fat intake have led to significant decreases in serum cholesterol in many populations, and may have contributed to the decline in coronary heart disease mortality observed in several countries beginning in the 1970s and 1980s. Public health interventions don’t happen in isolation, and nutrition is not a zero-sum game. The story is more complex than heroes and villains.

What’s harder to quantify is the cultural and institutional momentum that followed. The review article didn’t just contribute to scientific debate—it helped crystallize a narrative that shaped dietary guidelines, food policies, and clinical messaging for decades. School lunches. The food pyramid. Airline meals. Medical training. All, in some way, bore the imprint of that foundational shift.

We may never know precisely how powerful the ripple effect of the NEJM articles was. But we do know this: when industry influences the framing of science, the risks go far beyond a single conclusion. They reverberate in the questions that aren’t asked, in the silence around emerging evidence, and in the slow erosion of public trust.

Epilogue: Aftertaste

Looking back from the vantage point of modern medicine, one thing is clear: Project 226 wasn’t just about sugar—it was about how scientific narratives are built.

Cristin Kearns didn’t merely uncover a funding relationship. She uncovered a deliberate effort to shape scientific consensus at a critical juncture in the history of nutrition. Her discovery reminds us that the boundary between influence and manipulation is thin, and that even subtle shifts in emphasis can shape policy, education, and personal health decisions for generations.

To be fair, industry funding doesn’t automatically discredit scientific work. Many significant advances have resulted from public-private partnerships. But when vested interests dictate which questions get asked—or how inconvenient findings are framed—the integrity of science is at risk.

Because if medical truth is shaped in quiet rooms, behind grant proposals and editorial decisions, then it’s our job, not just as physicians but as citizens, to ask who’s in the room. And why.

The legacy of The Sugar Papers isn’t just in the past. It’s in the reminder that scientific credibility must be earned, protected, and constantly re-examined.

Not just for the sake of history. But for the people who live with its consequences.

While this article is grounded in verified documents, published research, and credible reporting, certain scenes—such as private conversations or atmospheres—have been creatively reconstructed to enhance narrative flow. These dramatizations aim to bring historical events to life without compromising factual integrity.

Sources & Further Reading

- Kearns CE, Schmidt LA, Glantz SA. Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1680–1685. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394

- McGandy RB, Hegsted DM, Stare FJ. Dietary fats, carbohydrates and atherosclerotic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. Part 1: 1967 Jul 27;277(4):186–192. Part 2: 1967 August 3;277(5):242–247.

- Yudkin J. Pure, White and Deadly. London: Davis-Poynter; 1972.

- Taubes, G. The Case Against Sugar. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2016.

- Fernandez, E. UCSF reveals how the sugar industry influenced the national conversation on heart disease. UCSF News. September 12, 2016.

- Burdy C. Behind the sugar industry’s 50-year mission to axe its link to heart disease. Quartz. September 12, 2016.

- Associated Press. Sugar industry paid scientists for favourable research, documents reveal. September 13, 2016.

- Huehnergarth NF. Sugar Industry Quashed Link Between Sugar And Heart Disease Over 50 Years Ago, Says Report. Forbes. September 12, 2016.

- Whiteman, H. (2016, September 12). Sugar and Heart Disease: The Sour Side of Industry-Funded Research. HuffPost

- Glantz SA. Sugar Papers Reveal Industry Role in Shifting National Heart Disease Focus to Saturated Fat. UCSF Blog. September 13, 2016.

- Glantz SA. Report claims sugar industry hid connection to heart disease for decades. The Washington Post. November 22, 2017.

- O’Connor, A. How the Sugar Industry Shifted Blame to Fat. The New York Times. September 12, 2016.

- Nestle M. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. University of California Press; 2002.

- Lustig RH. Sugar Has 56 Names: A Shopper’s Guide. Avery, 2012.

- Kearns CE, Glantz SA, Schmidt LA. Documents Reveal Sugar Industry Influence on 1970s US Dental Research. PLoS Biol. 2017;15(3):e2003460. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003460

- Moss M. Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. Random House; 2013.

- Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al.

“Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000.”

New England Journal of Medicine. 2007 Jun 7;356(23):2388–2398. - Aspelund T, Gudnason V, Magnusdottir BT, Andersen K, Sigurdsson G, Thorsson B, Steingrimsdottir L, Critchley J, Bennett K, O’Flaherty M, Capewell S. Analysing the large decline in coronary heart disease mortality in the Icelandic population aged 25-74 between the years 1981 and 2006. PLoS One. 2010 Nov 12;5(11):e13957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013957. PMID: 21103050; PMCID: PMC2980472.

- Mensink RP, Zock PL, Kester AD, Katan MB.

“Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials.”Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 May;77(5):1146–1155.

Parts of this article were developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, a large language model by OpenAI. The author guided and edited all content to ensure historical accuracy, narrative integrity, and medical relevance.

Interesting, I recently read about this in ‘The Great Cholesterol Myth’ by Bowden and Sinatra. They dive more into the nutritional studies side as well.

Great! Sugar and HCFS is killing millions and yet here we are. Thanks for bringing attention to the big cover up. Maybe someday sugar will end up like smoking – safe, legal, and rare (or at least rarer than it otherwise would have been).

Very interesting and important that the truth is coming to light. It will likely take a long time to undo all the damage this has caused.

A fascinating read…and confirmation of long-held suspicions regarding refined sugar. I was originally warned about refined sugar ~45yrs ago by a man I worked for who was both exceptionally bright (spoke 7 languages) and a diabetic; he compared refined sugar to heroin. Thank you for sharing.🙏

You’re very welcome Don — and thank you for sharing that vivid memory. Comparing refined sugar to heroin might sound extreme to some, but it’s striking how often those who’ve lived with diabetes or studied metabolism closely arrive at that same metaphor. It speaks to how powerfully sugar can affect both our physiology and behavior. I’m glad the article resonated and affirmed what you’ve long suspected.