Estimated reading time: 27 minutes

Heart failure is a common medical condition and remains an increasing global problem.

In many ways, heart failure is synonymous with end-stage heart disease. Of course, prognosis varies depending on the severity of the disorder. However, in advanced heart failure survival is dismal.

All diseases of the heart may ultimately lead to heart failure.

A simple way of defining heart failure is to say that it is a condition that arises when the heart muscle is not able to accomplish its primary role which is to continuously receive and pump blood through the body’s arteries and veins. The inability of the heart to do so may affect every organ in the body and lead to diverse symptoms that negatively affect quality of life.

Recent reports indicate that heart failure affects 6.5 million people in the US. aged 20 years or older (1).

Due to improved survival of patients with heart disease, heart failure will likely continue to increase in prominence.

Furthermore, it is well established that the risk of heart failure increases with advancing age. With the growing number of elderly people, the burden of the disorder will continue to pose challenges for future healthcare.

The American Heart Association (AHA) predicts a 46% increase in prevalence from the year 2012 to the year 2030, resulting in 8 million or more Americans aged 18 years or older with heart failure (1).

It is estimated that heart failure accounts for 1-2% of all healthcare expenditure (2). The bulk of these costs are driven by frequent, prolonged, and repeat hospitalizations (3).

1. What Is Heart Failure?

In medical literature, heart failure is generally not considered to be a disease. Instead, it is a syndrome or a constellation of symptoms, usually resulting from an underlying pathology of the heart.

Controversy has always surrounded the use of the phrase heart failure, partly because advances in physiology have rendered earlier definitions inadequate. Furthermore, the clinical scientist may sometimes use the term differently than the clinical physician (4).

Many attempts have been made to come up with a comprehensive set of criteria that describe heart failure.

In 1950, Dr. Paul Wood defined heart failure as a state in which the heart fails to maintain an adequate circulation for the needs of the body despite a satisfactory filling pressure (5).

In 1980, Dr. Eugene Braunwald defined the condition as a pathophysiological state in which an abnormality of cardiac function is responsible for the failure of the heart to pump blood at a rate commensurate with the requirements of the metabolizing tissues (5).

In 1985, Dr. Phillip Poole Wilson, defined heart failure as a clinical syndrome caused by an abnormality of the heart and recognized by a characteristic pattern of hemodynamic, renal, neural and hormonal responses (5).

According to the current definition by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood (6).

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently defined heart failure as a clinical syndrome characterized by typical symptoms (e.g., breathlessness, ankle swelling, and fatigue) that may be accompanied by signs (e.g. elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary crackles and peripheral edema) caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality, resulting in a reduced cardiac output and/or elevated intracardiac pressures at rest or during stress (7).

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome that results from a structural or functional impairment of the pumping capacity and/or filling of the left ventricle of the heart. It is characterized by shortness of breath, ankle swelling, and fatigue.

2. How Common Is Heart Failure?

During the 1980s, the Framingham study reported that the prevalence of heart failure increased dramatically with increasing age, with an approximate doubling in the prevalence with each decade of aging (8)

The age-adjusted annual incidence was 0.14% in women and 0.23% in men. Survival in the women was generally better than in the men, leading to the same point prevalence.

Since then it is well established that the risk of heart failure increases with advancing age, with an incidence of 0.3 per 1,000 in those <55 years old up to 18 per 1,000 for those ≥85 years (9).

Heart failure is present in 2 percent of persons age 40 to 59 and 5 percent of persons age 60 to 69.

African-Americans are 1.5 times more likely to develop the condition than Caucasians.

During the 1990s, there was a rising trend in the incidence and prevalence of heart failure leading many experts predicted that it would become an epidemic during the first decades of the new millennium. However, the incidence of heart failure-related deaths in the U.S. seemed to decrease between 2000 – 2012.

Recent data shows that heart failure deaths rose again between 2012-2014, particularly among men and non-Hispanic black populations (10).

The risk of heart failure increases with advancing age. Heart failure is present in 2 percent of persons age 40 to 59 and 5 percent of persons age 60 to 69.

3. What Are the Most Common Causes of Heart Failure?

As heart failure in itself is not considered to be a disease, it is imperative to establish the underlying disorder that causes heart failure to occur.

In the 1970s, high blood pressure (hypertension) and coronary artery disease were the primary causes of heart failure in the United States and Europe. Disorders of the heart valves were also considered as common causes.

More recently, hypertension and valve disorders are less often considered to be the underlying cause of heart failure, probably due to improvements in the detection and treatments of these disorders (11).

At the same time, coronary artery disease, obesity, and diabetes mellitus have become increasingly responsible for heart failure.

In fact, multiple risk factors may co-exist and interact with each other in an individual patient. Studies show that the burden of risk factors in patients with established heart failure has increased over time (12). Hence, several disorders, such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, are often present in the same patient.

Smoking is a strong risk factor for heart failure (13).

Several diseases of the heart muscle itself, so-called cardiomyopathies, are relatively common causes of heart failure, particularly among younger people.

Myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle commonly caused by a virus infection are also known underlying causes.

Congenital heart defects may lead to heart failure later in life.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), overconsumption of alcohol, and abnormal heart rhythms, such as atrial fibrillation, may sometimes cause heart failure.may sometimes lead to heart failure.

Lately, exposure to cardiotoxic drugs (e.g., anthracyclines used for the treatment of cancer) have become a relatively common underlying cause of the condition.

It is imperative to establish the underlying cause of heart failure in every patient. Coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, heart valve disorders, obesity, diabetes, heart arrhythmia, and congenital heart defects are the most common causes.

4. What Is Systolic Heart Failure?

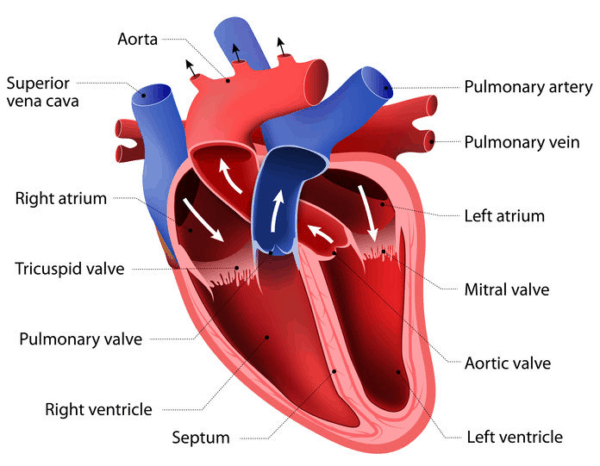

Heart failure is characterized by a dysfunction of the heart muscle, usually the left ventricle.

The left ventricle is responsible for pumping oxygenated blood to all the tissues and organs of the body. By contrast, the right ventricle solely pumps blood through the lungs.

Conditions leading to damage of the heart muscle and reduced pump capacity of the left ventricle commonly lead to heart failure. A typical example is a patient with a history of coronary heart disease and previous heart attack (myocardial infarction).

Systolic heart failure, also called heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, describes a condition caused by the inability of the heart muscle to contract normally. Hence, blood flow to vital organs is limited, leading to many of the symptoms of heart failure.

Systolic heart failure, also called heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, describes heart failure caused by the inability of the heart muscle to contract normally.

5. What Is Ejection Fraction (EF)?

An ejection fraction (EF) is an essential measurement of how well the heart muscle is pumping. Despite some limitations, EF is used to help classify heart failure and guide treatment.

EF is a measurement, expressed as a percentage, of how much blood the left ventricle pumps out with each contraction. An ejection fraction of 60 percent means that 60 percent of the total amount of blood in the left ventricle is pushed out with each heartbeat (14).

In a healthy heart, the EF is 50 percent or more.

- An ejection fraction of 55 percent or higher is considered normal.

- An ejection fraction of 50 percent or lower is considered reduced.

- An ejection fraction between 50 and 55 percent is usually considered “borderline (15).”

The following methods may be used to calculate EF:

- Echocardiogram – the most widely used test

- MUGA scan

- CT scan

- Cardiac catheterization

- Nuclear stress test

Ejection fraction (EF) is a measurement, expressed as a percentage, of how much blood the left ventricle pumps out with each contraction.

6. What Is Heart Failure with a Normal Ejection Fraction (HFNEF)?

In many patients with heart failure, the pumping capacity of the heart muscle is preserved. This has variously been labeled as diastolic heart failure, heart failure with preserved left ventricular function or heart failure with a normal ejection fraction (HFNEF)(16).

Various cutoffs for ejection fraction have been used to define HFNEF, usually ranging from 40 to 50% (17).

Interestingly, approximately 30–50% of patients with heart failure have a normal or near-normal contraction of the left ventricle function (18). Hence, a large fraction of patients with heart failure do not have systolic heart failure.

HFNEF is a major public health problem in the western world, currently representing approximately half of all the patients with heart failure (19). It is especially common in elderly people with comorbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and coronary artery disease.

Heart failure with a normal ejection fraction (HFNEF) describes heart failure where the pumping capacity of the heart muscle is preserved. HFNEF is a major public health problem in the western world, currently representing approximately half of all the patients with heart failure.

7. What Is Diastolic Heart Failure?

In diastolic heart failure, the left ventricle loses its ability to relax normally, usually due to increased stiffness of the heart muscle. Hence, the left ventricular chamber may not fill adequately with blood during the resting period between each heartbeat (diastole).

When the left ventricle becomes stiff, diastolic pressure also called filling pressure, increases. The increased pressure is transported back to the lungs, leading to elevated pressure within the pulmonary circulation. This may cause shortness of breath and even cause congestion of the lungs which, if severe, may lead to pulmonary edema.

Sometimes heart failure with normal ejection fraction (HFNEF) is regarded as diastolic heart failure. However, this is an oversimplification.

Of course, many patients with HFNEF have diastolic dysfunction, but usually, other factors come into the picture. Hence, diastolic dysfunction may not be the sole cause of symptoms in these patients.

Primary diastolic dysfunction is typically seen in patients with hypertension. It is commonly associated with thickening (hypertrophy) of the left ventricle, has a particularly high prevalence in the elderly population and is more common in women than men.

Although diastolic heart failure is regarded as common in clinical practice, its existence has been questioned for several reasons (20).

Firstly, many of these patients may not indeed have heart failure. Instead, their symptoms may be caused by other conditions such as obesity or pulmonary disease that can mimic heart failure (21).

Some patients with HFNEF may even have subtle abnormalities of systolic function although the ventricular ejection fraction is normal (22).

The diagnosis and treatment of diastolic heart failure has lagged behind that of systolic heart failure mainly to the heterogeneity of HFNEF.

However, diastolic heart failure seldom occurs in isolation. Most patients with diastolic heart failure don’t have an entirely preserved systolic function. Thus, the term HFNEF is preferred.

In diastolic heart failure, the left ventricle loses its ability to relax normally, usually due to increased stiffness of the heart muscle. However, diastolic heart failure seldom occurs in isolation. Many other disorders, such as obesity, diabetes, and lung disease, are often present as well and systolic function is not always preserved. Hence, the term heart failure with normal ejection fraction (HFNEF) is generally preferred.

8. What Are The Symptoms of Heart Failure?

Breathlessness (dyspnea), fatigue, and exercise intolerance are key symptoms of heart failure. Initially, breathlessness is mainly present on exertion, but in the later stages, it may be present at rest.

Orthopnea (dyspnea when lying down, usually in the supine position) is typical.

Furthermore, nocturnal episodes of dyspnea (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea) may be present. Then, the patient typically experiences sudden attacks of shortness of breath, which awakens him/her from sleep.

Fatigue and weakness are common features.

Patients with heart failure commonly have a reduced ability to excrete sodium and water through the kidneys leading to what is often called refractory volume overload.

Volume overload can manifest as pulmonary congestion (collection of fluid in the lungs), peripheral edema (swollen legs and ankles), and elevated jugular venous pressure.

Furthermore, swelling of the abdomen may occur if fluid accumulates in the abdominal cavity.

Some patients may experience a persistent cough or wheeze with white or pink blood-tinged phlegm (23)

Unintentional weight loss, sometimes leading to cachexia, is a common complication of advanced heart failure (24).

Signs of inadequate perfusion with low blood pressure (hypotension) cold extremities and mental status changes are also signs of advanced disease. At this stage, renal function often becomes impaired as well.

The most common symptoms of heart failure are breathlessness (dyspnea), fatigue, exercise intolerance, and refractory volume overload leading to edema. Other symptoms include cough, lack of appetite, nausea, and swelling of the abdomen.

9. What Is Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction (ALVSD)?

Many patients with reduced ejection fraction do not have symptoms of heart failure. Because of the absence of symptoms, they are not considered to have heart failure. This condition is called asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ALVSD).

ALVSD is at least as common as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Patients with ALVSD are at risk of progression to symptomatic heart failure (25).

Studies have used a variety of thresholds for ejection fraction, ranging from 30 to 54 percent, to identify left ventricular systolic dysfunction (26).

The causes of ALVSD include coronary heart disease, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, valve disease, hypertension, and exposure to cardiotoxic drugs (e.g., , anthracyclines).

The rationale for early detection of ALVSD is that appropriate pharmacologic therapy can significantly improve outcomes in patients with ALVSD if ejection fraction is ≤35 to 40 percent (27).

Asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ALVSD) is considered present when ejection fraction (EF) is reduced, but no symptoms of heart failure are present.

10. What Are the Stages of Heart Failure?

Heart failure is a chronic long-term condition that tends to gets worse with time.

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association has defined four stages (28). The stages cover a broad spectrum ranging from asymptomatic people risk factors for heart disease to refractory end-stage heart failure.

Stage A: Patients at risk for heart failure who have not yet developed structural heart changes (i.e., those with diabetes or coronary artery disease without prior heart attack)

Stage B: Patients with structural heart disease (i.e., reduced ejection fraction, left ventricular hypertrophy, chamber enlargement) who have not yet developed symptoms of heart failure

Stage C: Patients who have developed clinical heart failure

Stage D: Patients with refractory heart failure requiring advanced intervention.

Stage A is considered pre-heart failure. Patients with stage A have no structural damage to the heart.

Stage A includes patients with known coronary artery disease, individuals with conventional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. It also includes people with a history of alcohol abuse, family history of cardiomyopathy, history of taking drugs that may damage the heart muscle, such as some cancer drugs.

Stage B includes patients with asymptomatic left ventricular function. These patients have signs of structural damage to the heart but have not yet developed symptoms of heart failure.

Stage C and D include patients with symptomatic heart failure with stage D representing end-stage disease.

The four stages of heart failure (A, B, C, and D) cover a broad spectrum ranging from asymptomatic risk factors to refractory end-stage heart failure.

11. What Is the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification of Heart Failure?

The New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class is a subjective estimate of a patient’s functional ability based on symptoms (29)

| Class | Patient Symptoms |

| I | No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea (shortness of breath). |

| II | Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity results in fatigue, palpitation, dyspnea (shortness of breath). |

| III | Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes fatigue, palpitation, or dyspnea. |

| IV | Unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort. Symptoms of heart failure at rest. If any physical activity is undertaken, discomfort increases. |

The New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class is a subjective estimate of a patient’s functional ability based on the severity of symptoms. Patients in Class I have no limitation of physical activity. Patients in Class IV are unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort.

12. What Is the Difference Between Acute and Chronic Heart Failure?

Acute heart failure, sometimes called acute decompensated heart failure, is defined as a gradual or rapid change in signs and symptoms, resulting in a need for urgent therapy (30).

The symptoms are primarily the result of severe pulmonary congestion resulting in sudden shortness of breath.

Acute heart failure encompasses at least three distinct clinical entities (31):

- Worsening chronic heart failure associated with reduced or preserved ejection fraction (70 percent of all admissions)

- New-onset heart failure that may, for example, occur following a large myocardial infarction or a sudden increase in blood pressure superimposed in a stiff, noncompliant left ventricle (25 percent of all admissions).

- Advanced heart failure associated with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and a continually worsening low-output state (5 percent of all admissions).

Acute heart failure is an emergency and needs in-hospital treatment.

Chronic heart failure, also called congestive heart failure, on the other hand, is a long-term condition that can usually be kept stable with adequate treatment. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, problems exercising, fatigue, and swelling of the feet, ankles, and abdomen.

Acute heart failure is defined as a gradual or rapid change in heart failure signs and symptoms, resulting in a need for urgent therapy. The symptoms primarily occur from pulmonary congestion leading to sudden shortness of breath. Chronic heart failure is a long-term condition that can usually be kept stable with adequate treatment.

13. What Is Right-Sided Heart Failure?

The right ventricle of the heart pumps the blood out of the heart, through the pulmonary artery and into the lungs where it is replenished with oxygen.

In most cases, heart failure is caused by dysfunction of the left ventricle. Right-sided or right ventricular heart failure usually occurs as a result of left-sided failure.

When the left ventricle becomes dysfunctional, increased fluid pressure is transferred back through the lungs and ultimately to the right ventricle.

Increased fluid pressure in the lungs is called pulmonary hypertension. Although pulmonary hypertension can occur in isolation, it most commonly results from a dysfunction of the left ventricle.

The right ventricle has a limited capacity to deal with increased resistance caused by a pressure increase in the pulmonary circulation. Consequently, when the right ventricle starts to fail, blood backs up in the body’s veins, causing congestion and swelling of the legs and ankles. Furthermore, the liver may become congested, and fluid may accumulate in the abdominal cavity (ascites).

Right-sided heart failure is caused by dysfunction of the right ventricle. Right ventricular heart failure usually occurs as a result of left-sided failure. Symptoms include congestion and swelling of the legs and ankles and swelling of the abdomen.

14. How Is Heart Failure Diagnosed?

The approach to the patient with suspected heart failure includes the history and physical examination and diagnostic tests to help establish the diagnosis, assess severity, and determine the underlying cause (32).

It is essential to take a blood sample to assess hemoglobin, kidney function (serum creatinine), sodium and potassium, blood sugar, and liver enzymes.

A measurement of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) can help to confirm the diagnosis and severity of heart failure.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) will help to determine the rhythm of the heart. It may also provide information about previous damage to the heart muscle caused by a heart attack (myocardial infarction).

An ultrasound examination, also called echocardiogram, provides essential information about the structure of the heart, the heart valves, the pumping capacity of the heart muscle, the presence of pulmonary hypertension, and the the stiffness of the left ventricle (diastolic function). It is commonly used to calculate the ejection fraction (EF).

A chest X-ray may be used to determine if the heart is enlarged and whether there are signs of congestion of the lungs.

A stress test may be performed to assess how the heart responds to exertion.

A more specific stress test may be used to determine VO2 max, also known as maximal oxygen uptake. It is the measurement of the maximum amount of oxygen a person can utilize during intense exercise and is commonly used to measure cardiovascular fitness.

Computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide essential information about the anatomy and function of the heart muscle and heart valves. These imaging techniques may help determine the underlying cause of heart failure.

Coronary angiography is often performed to study the coronary arteries and whether coronary artery disease is present or not.

The approach to the patient with suspected heart failure includes the history and physical examination, and diagnostic tests to help establish the diagnosis, assess severity, and determine the underlying cause.

15. What Is the Role of Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) and N-Terminal-Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) are peptides (small proteins) produced by heart muscle cells (33).

BNP was initially named brain natriuretic peptide because it was first found in brain tissue. However, BNP is actually produced primarily by cells in the left ventricle of the heart.

Small amounts of a precursor protein, pro-BNP, are continuously produced by the heart muscle. Pro-BNP is then split by to release the active hormone BNP and an inactive fragment, NT-proBNP, into the blood.

BNP has many biologic functions. It increases the excretion of sodium and water through the kidneys (diuretic effect). It also reduces the secretion of aldosterone from the adrenal glands, and it relaxes vascular smooth muscles in arteries and veins (vasodilatation).

The concentrations of BNP and NT-proBNP produced can increase markedly in patients with left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure.

Measurements of plasma BNP are helpful in the evaluation of patients with dyspnea. They are commonly used for the evaluation of suspected heart failure when the diagnosis is uncertain (34). Hence, the main clinical utility of either BNP or NT-proBNP is that a normal level will help to rule out heart failure.

In general, the following cut off values may be employed for patients with acute dyspnea (35):

| BNP | NT-proBNP |

| < 100 pg/mL – heart failure unlikely | < 300 pg/mL – heart failure unlikely |

| >400 pg/mL – heart failure likely | Age < 50 years, NT-proBNP >450 pg/mL – heart failure likely |

| 100-400 pg/mL – use clinical judgment | Age 50-75 years, NT-proBNP >900 pg/mL – heart failure likely |

| Age >75 years, NT-proBNP >1800 pg/mL – heart failure likely |

Plasma BNP also provides prognostic information in patients with chronic heart failure and those with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic LV dysfunction (36)

Measurements of BNP and NT-pro BNP may be used to monitor patients with heart failure, especially those with moderate to severe symptoms. A rise in plasma BNP above the patient’s own baseline value should trigger closer assessment for a possible worsening of the condition.

The main clinical utility of either BNP or NT-proBNP is that a normal level will help to rule out heart failure. Measurements of BNP and NT-pro BNP may also be used to monitor patients with established heart failure.

16. What Is the Prognosis of Patients with Heart Failure?

Unfortunately, the prognosis for patients with advanced heart failure has remained alarmingly poor over the last thirty years. However, long-term mortality rates have improved over time (37).

On the other hand, left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure cover a broad spectrum ranging from minimal symptoms to advanced disease. Hence it is vital to acknowledge that prognosis varies according to the stage of the condition.

The two leading causes of death in patients with heart failure are sudden death and progressive pump failure. Evidence suggests that approximately 30 to 50 percent of all cardiac deaths in patients with heart failure are sudden deaths (38).

There are some data to suggest that heart failure-related mortality is comparable to that of cancer (39). For example, in the original and subsequent Framingham cohort, the probability of someone with a diagnosis of heart failure dying within five years was 62% and 75% in men and 38% and 42% in women, respectively (40). In comparison, five-year survival for all cancers among men and women in the US during the same period was approximately 50%.

The need for hospitalization is an important marker for poor prognosis (41).

The mortality rate in treated patients with heart failure increases with age.

Most studies suggest that the prognosis is better in women than men (42).

A study from the Mayo Clinic showed that for the periods 1979 to 1984 compared with 1996 to 2000, the one-year mortality fell from 30 to 21 percent in men and from 20 to 17 percent in women in patients hospitalized for heart failure. The five-year mortality fell from 65 to 50 percent in men and from 51 to 46 percent in women (43).

Advanced heart failure has a dismal prognosis. The mortality rate increases with age but prognosis is better in women than men. Hospitalization for heart failure is a marker for poor prognosis.

17. How Is Heart Failure Treated?

The treatment of heart failure depends on the underlying cause and the severity of symptoms.

In patients with stage A and B the, main goal is the prevent the occurrence of clinical heart failure.

Patients at risk of heart failure but no structural damage to the heart (stage A) should quit smoking and exercise regularly. High blood pressure and lipid disorders should be treated. Alcohol should be used in moderation or not at all. Underlying conditions, such as diabetes and coronary heart disease, should be addressed.

Patients with heart disease without signs of heart failure (stage B) should be treated according to the underlying condition. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are recommended for patients with left ventricular dysfunction (44).

Acetylsalicylic acid (baby aspirin) and statins are recommended for patients with established coronary artery disease.

Beta-blockers are usually recommended for patients who have suffered a heart attack (myocardial infarction).

Patients with symptomatic heart failure (stage D and E) usually need diuretic drugs to relieve congestive symptoms and restricting dietary sodium intake is generally recommended. Furosemide is the most commonly used loop diuretic for the treatment.

In patients with stage E and D, treatment with ACE inhibitors, ARB’s or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI) is recommended. A beta-blocker should be added if tolerated. Aldosterone antagonists (antimineralocorticoid) should be added on top of this treatment. All these drugs may improve prognosis and reduce the need for hospitalizations, particularly in patients with reduced ejection fraction (EF)(45).

African American patients may benefit from the addition of a hydralazine/nitrate combination (46).

Patients with advanced symptoms should be evaluated for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and the use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

The treatment of heart failure depends on the underlying cause and the severity of symptoms. Prevention is the main target in patients with stage A and B heart failure. Patients with stage D and E should be given multidrug therapy to limit the progression of the disorder and improve prognosis.

18. What Is the Role of Cardiac Resynchronization (Therapy CRT)?

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), also called biventricular pacing, may benefit heart failure patients with moderate to severe symptoms and whose left and right heart chambers do not beat in unison.

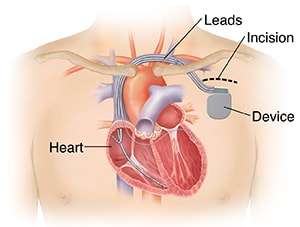

The CRT pacing device is an electronic, battery-powered device that is surgically implanted under the skin.

The device has 2 or 3 leads (wires) that are positioned in the right atrium, right ventricle, and the left ventricle (via the coronary sinus vein) (47). The leads are implanted through a vein.

CRT is not valid for everyone and is not recommended for those with mild symptoms or diastolic heart failure.

Furthermore, CRT is only useful when the left and right heart chambers do not beat synchronously. Whether this is the cased can usually be found out on a regular twelve lead electrocardiogram (ECG).

Most patients who receive a CRT device have a left bundle branch block (LBBB) on the ECG.

There are two types of CRT devices. Depending on your heart failure condition, a Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Pacemaker (CRT-P) or a Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Defibrillator (CRT-D).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), also called biventricular pacing may benefit heart failure patients with moderate to severe symptoms and whose left and right heart chambers do not beat in unison.

19. What Is the Role of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (ICD)?

Studies suggest that approximately 30 to 50 percent of all cardiac deaths in patients with heart failure are sudden deaths (35). These deaths are usually caused by lethal arrhythmia, most often sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation.

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a battery-powered device placed under the skin. The device keeps track of the heart rhythm. Wires connect the ICD to the heart through a vein. If an abnormal, fast heart rhythm is detected, the device will deliver an electric shock to restore a normal heartbeat.

ICDs are useful in preventing sudden death in patients with known, sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation or high risk of such arrhythmias.

Selecting patients for ICD treatment is complicated because the devices do not benefit all patients with heart failure.

The usefulness of ICD depends on the severity of left ventricular systolic dysfunction, the underlying cause of heart failure, and the severity of symptoms (48).

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a battery-powered device placed under the skin that keeps track of the heart rhythm. If an abnormal, fast heart rhythm is detected, the device will deliver an electric shock to restore a normal heartbeat.

20. What Is a Ventricular Assist Device (VAD)?

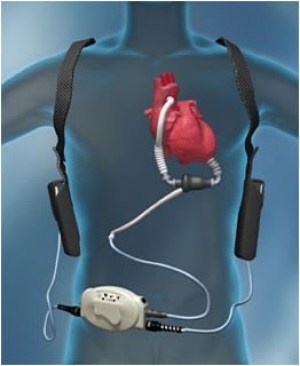

A ventricular assist device (VAD) is an implantable pump that helps pump blood from the ventricles.

A VAD is most frequently used to assist the left ventricle. Hence, the term left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

The devices are only used in patients with advanced, end-stage heart failure.

A VAD can be used both temporarily, for example, while waiting for heart transplantation (bridge to transplantation), or as permanent support.

Interestingly, VAD’s may be quite useful in relieving symptoms (49). Patients may even be able to exercise and return to work.

However, the use of VAD’s is sophisticated, and there is a risk of complications, including infections, neurological events, pump thrombosis blood clotting), and bleeding.

A ventricular assist device (VAD) is an implantable pump that helps pump blood from the ventricles. VAD’s are only used in patients with advanced, end-stage heart failure.

21. What Is the Role of Heart Transplantation?

Heart transplantation is the procedure by which the failing heart is replaced with another heart from a suitable donor.

It is generally reserved for patients with end-stage heart failure who are estimated to have less than one year to live without a transplant and who are not candidates for or have not been helped by conventional medical therapy (50).

Candidates for heart transplantation usually have New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III (moderate) symptoms or class IV (severe) symptoms and en ejection fraction lower than 25 percent.

Immunosuppressive drug therapy is started soon after surgery to prevent rejection of the new organ.

A thorough workup is necessary to decide if a patient is a candidate for heart transplantation.

The upper age limit is generally considered to be 65 years. However, older patients may also be treated under specific circumstances.

Patients with active systemic infection, severe underlying disease (e.g., cancer, collagen-vascular disease), ongoing history of substance abuse (e.g., alcohol, drugs, or tobacco), psychosocial instability or inability to cope with follow-up care are not candidates for heart transplantation.

Heart transplantation is the procedure by which the failing heart is replaced with another heart from a suitable donor. It is generally reserved for patients with end-stage heart failure who are estimated to have less than one year to live without the transplant and who are not candidates for or have not been helped by conventional medical therapy.

Discover more from Doc's Opinion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Heart failure cannot be cured though there is a range of treatment options available to manage and improve quality of life.