Estimated reading time: 18 minutes

Being a flight attendant is one of the most wanted professions in the world. The association with elegance, confidence, and reliability make it unique – a job to be proud of.

Flight attendants are employed and trained to perform safety functions on aircraft as well as customer service. Hence, being calm, collected, quick thinking, pleasant, and flexible are much-needed characteristics.

Of course, most of the time, the only things you have to do is to put on your uniform, go through the regular security routine, be polite with the passengers and serve food and drinks?

As a bonus, you will probably have a lot of leisure time and flexibility? And you get to see new places and learn about distinctive cultures all the time?

You might even make new friends all over the world.

But let’s be more pragmatic? For every two minutes of glamour, there are eight hours of hard work. And, I’m sorry to say, you might even be gambling with your health.

However, before we dig into the medical issues, let’s explore some history.

Early History

It is almost one hundred years since being a cabin or flight attendant became known as an occupation.

In March 1912, Heinrich Kubis became the first flight attendant in history when he served passengers on the German airline DELAG (1).

Kubis, famous for serving Zeppelin passengers, was in Hindenburg’s dining room when the ship burst into flame at Lakehurst, New Jersey on May 6 1937. He encouraged passengers and crew to jump from the windows and then jumped to safety himself (2).

When passenger air travel began in the early 1920s, flight attendants were called couriers. They were often the sons of businessmen who had financed the airlines (1).

In 1922, the British company “Daimler Airways” hired “cabin boys,” whose job was to assist passengers by handing out leather steamer rugs, hot water bottles, and cotton earplugs. They reassured passengers during the flight and helped them during landing and when disembarking the aircraft (3).

On 15 May 1930 Ellen Church, a registered nurse, was the first appointed American senior flight attendant. She operated a flight with eleven passengers on board an aircraft flying from San Francisco to Cheyenne.

Church’s duties included winding the clock in the cockpit, killing the flies after take-off, and preventing passengers from throwing cigarette stumps out of the windows. She was also supposed to clean passengers’ shoes, if necessary (3).

In 1930 “Boeing Air Transport” hired eight women flight attendants, historically known as the “Original Eight.” By the late 1930s, United airlines hired stewardess or “female helpers.” Initially, these were registered nurses (1).

Back in those days, the airplanes, mostly DC-3, were noisy and uncomfortable compared with today. The idea was that air travelers would feel safer in the hands of the stewardess, whose main job often was to attend those who became airsick.

According to sources, stewardesses were often treated poorly by male passengers, groping, pinching, and padding their butts (1).

Initially, the airlines required the stewardess to take an oath that she would not marry nor have children.

The first in-flight hostesses during the 1930s and 1940s wore military-inspired skirt suits in bland hues with white gloves and matching hats (4).

In the 1940s, the functionality of uniforms improved as “restrained elegance” in the sky became the norm.

At that time, flying was often a unique experience. Passengers wore their most elegant outfits. Hence, airline cabins were full of tailored suits and of course, cigarette smoke.

Post World War II

In 1945, flight attendants founded the present-day Association of Flight Attendants union, formerly known as the Airline Stewardess Association, or “ALSA.”

In the 1950s, more and more airlines added age clauses to contracts for flight attendants and the profession grew into a symbol of sophistication and glamour.

In 1956, flight attendants were grounded at age 32. However, male flight attendants were allowed to fly until they reached their sixties (6).

In the 1960s, high fashion came to the skies. Restrained elegance was replaced by miniskirts and hot pants and stewardesses became a marketing tool for the airline companies.

The words of Braniff hostess Muffet Webb who in the year 1956 won the first Miss Skyway contest (a beauty pageant for flight attendants) certainly reflect the undertone when she said; “Does your wife know you’re flying with us?”

Back in those days, being an air stewardess became an extremely popular job. In 1967, TWA accepted fewer than three percent of its applicants—a lower acceptance rate than Harvard (6).

Modern Day

With the Airline Deregulation Act in 1978, U.S. federal law deregulated the airline industry, removing federal government control over areas such as fares, routes, and market entry of new airlines (7).

Hence, a free market was introduced in the commercial airline industry, leading to an increase in the number of flights, lower fares, increasing number of passengers, and consolidation of carriers.

Consequently, flying became less of a luxury. The word “stewardess” fell out of favor and was replaced by the more gender-neutral “flight attendant.”

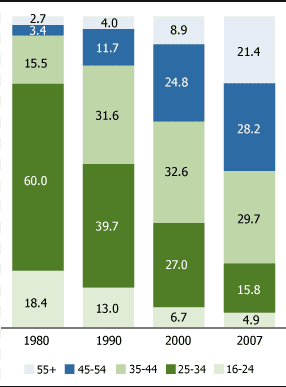

The age structure of flight attendants has changed dramatically since 1980. While flight attendants were younger than the overall U.S. workforce in 1980, they are now older (8).

Today, there are over 100,000 flight attendants in the U.S. (9).

According to the Population Research Bureau, half of all flight attendants are age 45 and older, and nearly 22 percent of them are 55 and older.

Although flight attendants continue to be predominantly female, males have increased their presence in the U.S. between 1980 (19.3 males per 100 females) and 2007 (26.4 males per 100 females) (8).

There has also been a dramatic shift in the earnings of flight attendants in the U.S. since 1980. After adjusting for inflation, the median hourly wages dropped by 26 percent between 1980 and 2007. In contrast, the median hourly wages of all U.S. workers rose by 13 percent during this period (8).

Asian countries still tend to use flight attendants as one of their unique selling points. Flight attendants have to be physically attractive and fit and fall within a stringent requirement of age, height, and weight.

The Health Risks of Being a Flight Attendant

Despite the unique occupational environment, the health consequences of flight attendant work have not been intensively studied.

Flight attendants are continuously exposed to a range of job-related exposures such as poor cabin air quality, cosmic ionizing radiation, elevated ozone levels, pesticides from cabin disinfection, high levels of occupational noise, circadian rhythm disruption, heavy physical job demands, and verbal and sexual harassment (10).

The flight attendant is the only person on an aircraft who is engaged in intense physical activity at reduced oxygen levels (11). Hence their health hazards may differ significantly from those of pilots and passengers

The most recent and reliable information about the health risks of being a flight attendant comes from the Harvard Flight Attendant Health Study (FAHS) (12, 13).

The study began in 2007 and has since then recruited over 12,000 people in 2 waves (14).

The Cabin Environment

The cruising altitude of commercial aircraft is usually maintained between 30.000 to 45.000 feet (9.100 to 13.700 m). Because the low atmospheric pressure at such heights is not compatible with survival, aircraft cabins are pressurized during flight to the equivalent of 5.000 to 8.000 feet (1.500 – 2.400 m) above sea level (15).

Hence, the partial pressure of oxygen in cabin air at cruising altitude is 25-30% lower than at sea level.

A part of the cabin air (40-50%) is recirculated and cleaned with special filters, while the remainder is derived from the outside air (bleed air). The humidity onboard ranges from 6-18% depending on the compartment. Optimal humidity varies between 40-70%. Hence, cabin air is arid (16).

The air conditioning and ventilation system on commercial aircraft maintain low counts of microorganisms in the cabin. However, there are reports of individuals contracting several infectious diseases through airborne transmission (17, 18).

Higher than standard rates of viral gastroenteritis, colds, and flu-like symptoms are reported in-flight attendants than other occupations (19).

While high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters effectively limit the risk of disease transmission, person-to-person transmission in the aircraft cabin may occasionally cause clusters of infections such as SARS, tuberculosis, coryza, influenza, measles, and meningitis. Furthermore, flight attendants may be exposed to infectious disease hazards during a layover.

For decades, flight attendants were exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke. Some of the health conditions caused by secondhand smoke in adults include coronary heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer (20).

Cabin Air Quality

There has been a significant reduction in cabin environment toxicological risks since the elimination of smoking onboard commercial aircraft (21).

Today, general concerns about air quality often focus on air dryness. Prolonged exposure to dry air is reported to cause symptoms of local irritation such nasal stuffiness, sore eyes, nose, throat, and chest wheeziness, or symptoms such as headache, fatigue, and difficulty in concentration.

In a Swedish study of flight attendants published in 2005, the most common complaint about cabin air quality was dry air (53%). Airline crew had more nasal, throat, and hand skin symptoms, than office workers did (22).

However, despite some recent improvements, there are still serious concerns about air quality incidents affecting flight attendants (23).

Flight attendants may be exposed to cabin air contamination by toxic substances from engine bleed air, ozone (in jet airliners not fitted with catalytic converters), or sources within the passenger cabin.

Many cases of severe symptoms from cabin air contamination have been reported.

Although the immediate health effects of exposure to contaminated cabin air have been relatively well documented, the causation, diagnosis, and treatment of long-term effects is still debated. However, why only some cabin occupants are particularly affected, and not others is unclear (24).

According to several data obtained from three U.S. airlines, frequency estimates of bleed air contamination events range from 0.09 to 3.88 incidents per 1,000 flight cycles. Using the lowest estimate of 0.09 events per 1,000 flight cycles, there may be an average of two to three contaminated bleed-air events every day (25).

The term “aerotoxic syndrome” is a phrase used by some experts to describe the short- and long-term health effects caused by contaminated cabin air (26). However, the concept of aerotoxic syndrome as a well-defined entity is still not recognized by the aviation medicine community (27).

Cosmic Ionizing Radiation

Cosmic ionizing radiation is a form of radiation that comes from outer space. A minimal amount of this radiation reaches the earth.

At flight altitudes, passengers and crew members are exposed to higher levels of ionizing radiation.

Cosmic radiation exposures on aircraft include galactic cosmic radiation, which is always present and solar particle events, sometimes called “solar flares (28).”

Evidence suggests that cosmic ionizing radiation causes cancer in humans (29). Ionizing radiation is also known to cause reproductive problems.

The National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements reported that aircrew has the largest average annual effective dose (3.07 mSv) of all U.S. radiation-exposed worker (30).

The European Cockpit Association (ECA) recommends air carriers to inform potential new employees about radiation exposure before recruitment. All employees should be aware that that high altitude flying exposes them to significantly higher ionizing radiation levels with associated health implications (31).

Reducing exposure times by flying fewer hours may help to reduce yearly limits of flight hours in the interest of flight safety.

Similarly, flight crew members may influence their lifelong radiation exposures by making use of their options regarding the selection of aircraft type(s) flown, the types of operation (short haul/ long haul), and their retirement age. Airline operators are encouraged to provide crews with the possibility of such career choices.

Cancer

In 2018, the FAHS reported that flight attendants have higher rates of several types of cancer than the general population (13).

In 2014 and 2015 the FAHS studied 5,300 flight attendants through surveys that were disseminated online, via mail and in person at airports. The surveys asked respondents about flight schedules and cancer diagnoses. The researchers then compared the responses to the health status of 2,729 non-flight attendant adults with similar socioeconomic backgrounds, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

The study revealed higher rates of uterine, cervical, breast, gastrointestinal, thyroid, and melanoma cancers among flight attendants. The gastrointestinal cancers included cancer of the colon, stomach, esophagus, liver, and the pancreas.

The disparity was most pronounced with breast, melanoma, and non-melanoma cancers. Flight attendants had more than double the risk of developing melanoma, and more than quadruple the risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancers. They also had a 51 percent higher risk of developing breast cancer than the general population.

Job tenure was associated with the risk of cancer among both females and males.

It is not clear why flight attendants appear to be at increased risk of several types of cancer. However, factors such as occupational exposure to ionizing radiation, circadian rhythm disruption with resulting sleep disorders, and previous exposure to secondhand smoke may all play a role.

Cabin crew members are also regularly exposed to more UV radiation than the general population

Furthermore, ongoing exposure to several chemical agents from engine leakages, pesticides, and flame retardants may be present. These contain compounds that may increase the risk of some cancers (32).

Obesity, Smoking, High Blood Pressure, and Disease of the Heart and Lungs

Data from the initial wave of the FAHS found about a 3-fold increase in the age-adjusted prevalence of chronic bronchitis among flight attendants despite considerably lower levels of smoking.

In addition, the prevalence of heart disease in female flight attendants was 3.5 times greater than the general population while their prevalence of high blood pressure (hypertension) and being overweight was significantly lower (12). Thus, chronic bronchitis and coronary artery disease were both more common among flight attendants compared to the general population

The more recent second wave of the FAHS found that flight attendants still had lower rates of overweight, obesity, and current smoking compared to the general publication (13). However, they also had a lower rate of heart and lung disease, which contrasts with the results from the first wave of the study.

Chronic bronchitis and coronary artery disease are both severe conditions that might impair the ability of flight attendants to perform their duties. Hence, flight attendants diagnosed with these conditions in 2007 (the first wave of the FAHS) may not have continued to work until the second wave of the study in 2015. This could partly explain the differences in the rates of heart and lung disease between the two waves of the study.

The “healthy worker effect” is a phenomenon explaining why workers usually exhibit lower overall death rates than the general population because the severely ill and chronically disabled are ordinarily excluded from employment (33).

Furthermore, smoking-related bronchitis and heart disease among flight crew presumably become less frequents as more time elapses since smoking bans were instituted on commercial flights.

Fatigue, Sleep, and Mental Health

Studies have indicated that fatigue is a significant problem among flight attendants (34).

The FAHS found an increased prevalence of adverse sleep and mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and alcohol abuse among flight attendants (13).

Fatigue and depression are symptoms that often coexist (35,36). Int the second wave of the FAHS, these conditions were much more common among flight attendants than in the general population.

Risk factors for mental health problems among flight crew may include extended and irregular working hours, sexual harassment, and lack of employer protections for occupational hazards (37).

Another study has reported elevated rates of suicide among cabin crew (38).

Sleep disorders, including circadian rhythm disruption, have been associated with adverse mental outcomes, including suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths (39).

An Italian mortality study on commercial flight crew found an increased risk for death by suicide among female flight attendants. This was also seen in male cockpit crew members but to a lesser extent. However, a lower than expected suicide risk was seen for male flight attendants (40).

It has been shown that job stressors such as mental and psychological demands, an imbalance between job demands and outside obligations, low supervisor support, and job dissatisfaction seem to predict psychological distress (41).

Experts have suggested that interventions aimed at reducing conflicts between work and private life, and at increasing social support for flight attendants may enhance their wellbeing and job satisfaction.

Infertility, Miscarriage, Preterm Birth, and Fetal Abnormalities

Reproductive problems, including adverse pregnancy outcomes, among female flight attendants have been reported since the 1960s (42).

Indeed, the second wave of the FAHS observed an association between job tenure as a flight attendant during a woman’s reproductive years and infertility, miscarriage, preterm birth, and fetal abnormalities (13).

Another study found an association between rates of miscarriages and circadian rhythm disruption, cosmic ionizing radiation exposure, and high physical job demands among flight attendants (43).

It is hugely worrying that cabin crew have the largest annual ionizing radiation dose of all U.S workers (30). Of course, this may be particularly problematic for pregnant flight attendants.

What is even more daunting is that these radiation exposures are not regulated among flight crew.

Musculoskeletal Symptoms

Flight attendants are at risk for musculoskeletal disorders.

Work-related strains and sprains of muscles, tendons, and supporting tissues can be caused by lifting, bending, carrying, reaching, working in confined spaces, and using repetitive motions.

Turbulence or sudden airplane movements are a frequent cause of injury among flight attendants.

Lower‐back musculoskeletal disorders are among the musculoskeletal problems most commonly reported by flight attendants.

Musculoskeletal symptoms may be associated with work-related psychological factors among flight crew, including mental job demands, harassment, and job insecurity (43).

Workplace Harassment and Abuse

Workplace harassment and abuse, especially against women, occur with high frequency worldwide (44).

Estimates suggest that as many as 50% of U.S. women experience sexual harassment during their working lives (45). However, only a minority report it.

A survey of cabin crew working for Australian airlines recently found that 65 percent experienced sexual harassment (46).

The research found that 70 per cent of cabin crew who experienced harassment said they chose not to report the incident because they did not think it would be dealt with appropriately or they were concerned reporting it would make the situation worse.

Incidents ranged from serious sexual assault, groping, passengers exposing themselves, sexualised and degrading remarks, and workers being abused because of their sexual orientation.

A 2018 survey by the U.S. Association of Flight Attendants (AFA) shows that than one-in-three flight attendants have experienced verbal sexual harassment from passengers, and nearly one-in-five have experienced physical sexual harassment from passengers, in the last year alone (47).

Only 7% of the flight attendants who experienced the abuse did report it to their employer.

Despite the high prevalence of abuse and the emergence of the #MeToo movement, 68 percent of flight attendants said they saw no efforts by airlines to address workplace sexual harassment over the last year (47).

Flight attendants may be particularly susceptible to harassment due to employment in a profession that is primarily female and has been previously sexualized by the airline industry. Furthermore, they are expected to suppress and regulate their emotional responses according to employer and passenger expectations (48).

Repeated exposure to sexual harassment, bullying, violence, and threats are related to physical and psychological wellbeing among flight attendants (37).

Another study observed strong associations between all types of abuse and depression, sleep disturbances, fatigue, workplace injuries, and musculoskeletal conditions among cabin crew (49).

The AFA has called on the entire airline industry to step up to combat harassment and recognize the impact it has on safety.

With flight attendants reporting that they often deal with harassment by avoiding further interaction with abusive passengers, airlines must also ensure that staffing levels on flights are sufficient to allow this strategy to work (47).

The Tailpiece

For the past fifteen years, I have, as an Aviation Medical Examiner, interviewed and examined thousands of flight attendants.

They have been females and males, young and older, experienced and inexperienced, confident and disheartened, healthy and sick, happy and unhappy, calm and agitated, smiling and crying. What most of them have in common is that they love their job and they are proud of their profession.

This article is dedicated to all those ambitious and devoted people.

I applaud your professionalism.

However, I can’t stop agonizing over your unpredictable occupational environment.

Nice blog! Very well written in an easy-to-understand manner. I appreciate your sincere efforts you have made in writing this kind of informative blog. Keep sharing!

What a great article – so well researched and presented in such a professional manner. I always wondered about those who take care of us in the air. And friends of mine who travel quite a lot for work by plane.

I wonder about my own health as well when I breathe in that jet engine fume in the cabin. Thank you for this article.

Hi Dr. Mo

Thank you for the kind words.

Appreciate your interest.

Axel

I appreciate the way Mr. Axel has shared such great information. As I’m a frequent traveler and I meet the humble flight attendants. I always wondered how they maintain their health. Finally, someone wrote on such an informative piece of article on them. Such a nice gesture by you Mr. Axel.

Very Good Post Thank You For Sharing Here On This Page

Nice insight.

Most of these are not told to the crew from their respective airlines because of commercial gains.

It is good to know one is at these risks.Also, to remember that flying is just a means to an end.Not a lifetime career.Even if the retirement age has been put, try to get your act together sooner, minimize flying or change to a more ground work and maximize and enjoy the potential you have in you as a crew member.You can do a lot.This was just a starting point.Do not get stuck there!

Then you will improve your health and explore the limitless opportunities that are outside of the Cabin and even those inside.

Great article. I always wanted to be a flight attendant. I still have hope.