Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, The Heart of Power – Episode 9: The Doctor Who Knew Too Much, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

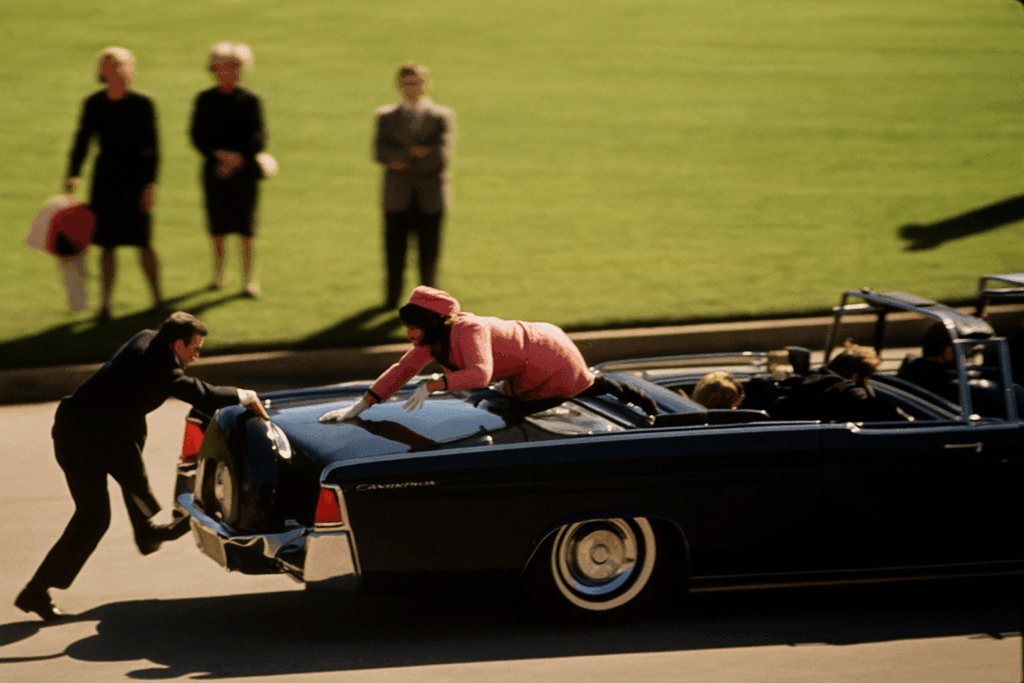

The sirens were still wailing as the limousine skidded to a halt at Parkland Hospital. Secret Service agents leapt out, blood on their sleeves, shouting for help. A stretcher rattled through the emergency doors with the President’s broken body.

Moments later, from another car in the motorcade, came his doctor. George Gregory Burkley walked quickly behind the chaos, face set like stone.

He had seen heart attacks, strokes, bullets, blood. But never this. John F. Kennedy’s body — pale, motionless, a head wound too devastating to disguise — was wheeled into Trauma Room One. The room filled with doctors barking orders, nurses rushing instruments, agents blocking the door.

Burkley didn’t shout. He didn’t push forward. He stood just inside the doorway, arms folded, watching. His eyes flicked from wound to wound, from monitor to face. He wasn’t just a witness. He was the man who had known Kennedy’s secrets long before this day — the Addison’s, the cortisone, the fragile spine, the medications. The world saw vigor; Burkley saw a body held together by chemistry and willpower.

Now, on this November afternoon in Dallas, all of that was over.

The doctors fought anyway, because that’s what doctors do. Tubes were placed. Blood was pushed. Hands pressed down on a chest already gone. A priest was summoned. Outside the door, Jacqueline Kennedy waited, dazed, her pink suit soaked and drying to brown. Burkley remained still. His job was no longer to save the president. It was to decide what would be remembered — and what would be hidden.

Later, at Bethesda, at the autopsy, his notes would raise questions that never went away. He would hint, years later, that the truth of Kennedy’s death was never fully told.

But in that moment, in the hospital corridor thick with sirens and whispers, Burkley already knew:

he was the keeper of secrets.

And secrets are heavier than bullets.

The Doctor Presidents Trusted

George Burkley never ran for office. He never gave speeches. Most Americans couldn’t have picked him out of a crowd.

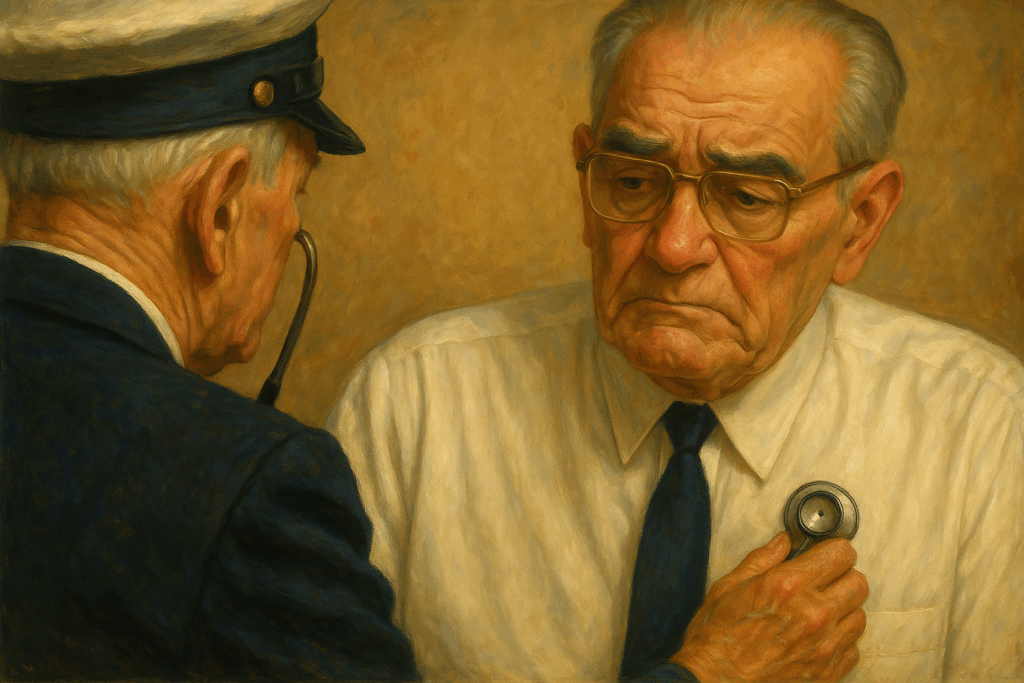

He was a Navy doctor, trained at the University of Pittsburgh, who had spent decades in uniform tending to sailors and admirals. By the mid-1950s he was a Captain, running the Naval Dispensary in Washington, a post that quietly linked him to the White House. Whenever Eisenhower retreated to Camp David — a Navy installation — Burkley was often sent along as a standby physician.

He wasn’t the man at Eisenhower’s bedside during the President’s 1955 heart attack — that drama belonged to Howard Snyder and Paul Dudley White. But Burkley saw the machinery around it: the guarded medical bulletins, the careful phrasing, the way a single diagnosis could shake Wall Street and stir fears in Moscow.

It was his apprenticeship in presidential medicine. A lesson that illness in the White House was never just illness. It was vulnerability. It was strategy. It was power.

When Kennedy took office in 1961, Burkley was already known, cleared, and trusted. The new President’s naval aide recommended him. He was steady, discreet, politically safe. Not a famous specialist who might seek headlines — but a career officer who knew how to keep things quiet.

At first, George Burkley bore the quiet title of Assistant Physician to the President, working in the shadow of Janet Travell, the trailblazing internist Kennedy had installed in 1961 as his personal doctor. For more than two years they operated side by side—Travell, the civilian pioneer, tending to Kennedy’s battered back with her unorthodox therapies; Burkley, the Navy admiral, steady and discreet, covering the daily grind of travel, emergencies, and official duties.

Kennedy’s Fragile Vigor

The cameras showed a golden boy — tanned, athletic, the youngest president ever elected. He jogged on beaches, played touch football, sailed with ease. The world saw vigor.

George Burkley saw something else.

Behind the image lay a body under siege: Addison’s disease, a spine fused by surgery, chronic infections, and a pharmacy’s worth of steroids, narcotics, and stimulants. By 1961, Kennedy was taking more medication than most patients twice his age.

Burkley was no longer the quiet assistant. By 1963, he had become the indispensable physician at Kennedy’s side — the Navy doctor who tracked the cortisone, stimulants, and painkillers that kept the President moving. He carried emergency vials on every trip abroad, adjusted regimens when fatigue or pain broke through, and kept a meticulous eye on the balance of drugs.

Travell still held the title of personal physician in Washington, but her experimental therapies and complicated routines were increasingly sidelined. In the day-to-day life of the presidency, it was Burkley who stood guard over the fragile machinery of Kennedy’s health.

The paradox was stark. Kennedy projected vitality while his body betrayed weakness. And Burkley was the architect of that illusion.

Years later, when asked, Burkley still refused to puncture the myth:

“President Kennedy was an essentially normal, healthy male, who had all the vigor and vitality, and much more so than the average male.”

The Addison’s? He dismissed it.

“The question of adrenal insufficiency… it was never a problem with the President.”

The heavy back brace Kennedy wore? Burkley downplayed it as trivial.

“It was just a small support rather than any actual brace.”

Burkley’s words preserved the illusion. Even four years after Dallas, he was still guarding Kennedy’s image.

The truth did not emerge until long after Burkley was gone.

For decades, Kennedy’s medical records were a locked vault, sealed tight by the family. Rumors swirled, journalists guessed, but hard proof never surfaced. The files sat hidden in the Kennedy Library until 1992, and even then access was tightly policed. It took another ten years before the seal was truly broken. In 2002, historian Robert Dallek was finally granted entry — and what he found confirmed the whispers: Addison’s disease, a spine racked by chronic pain, and a daily pharmacopoeia of steroids, narcotics, and stimulants that kept a young president upright.

The myth of vigor gave way to the reality of a body stitched together by medicine.

It had taken forty years for the world to learn what George Burkley had known all along — that the youthful vigor on camera was an illusion held together by medicine, secrecy, and willpower.

But in 1963, the cameras kept rolling. Kennedy kept smiling. And Burkley kept the secret.

Previous:

Episode 1. The Heart of Power: When Metabolic Disease Entered the Oval Office – William Howard Taft

Episode 2. The Heart of Power: The Golf Course Heart Attack – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Episode 3. The Heart of Power: The Stroke That Silenced a Dream – Woodrow Wilson

Episode 4. The Heart of Power: Built To Stand, Bound To Fall – John F Kennedy

Episode 5. The Heart of Power: Where Strength Sat Still – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Episode 6. The Heart of Power: The Ride Into the Sunset – Ronald Reagan

Episode 7. The Heart of Power: The Enemy Inside – Richard M Nixon

Episode 8 The Heart of Power: The Ticking Man – Lyndon B Johnson

📚 Sources & Further Reading

This article draws on official testimony, government archives, and published historical accounts to reconstruct Burkley’s role and the enduring mystery surrounding his silence.

-

William Manchester, The Death of a President (1967) — A dramatic, detailed account of the week of Kennedy’s assassination, written with access to many insiders.

-

Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History (2007) — A massive, modern investigation of the assassination and its controversies, including medical evidence.

-

Robert N. McClelland, Witness to History (2013) — Firsthand reflections from the Parkland surgeon who treated Kennedy.

-

National Archives: JFK Assassination Records Collection — The official archive, including autopsy files, testimony, and HSCA materials

Some portions of this article were developed with support from ChatGPT, an AI tool created by OpenAI. It was used to assist with research synthesis, narrative structure, and language refinement. All medical content, historical analysis, and editorial decisions were independently reviewed and finalized by the author.

These stories always motivate me to eat healthy, exercise, and get to sleep on time. I would rather be healthy than have a stack of money, a mansion, and a private jet. It’s a shame that Buckley remained quiet in his later years and that his daughter didn’t release his notes. It would have been very useful to see if Oswald acted alone.

I have a hard time seeing how any shots came from the front. If the throat wound was an entrance wound, where did it exit and why didn’t it hit someone in the secret service car 5 feet behind the presidential limousine? How did a shooter from the front thread the needle and shoot between the secret service agents in the front seat, the Connollys in the jump seats to hit JFK?

The attending physicians gave a press conference at Parkland Hospital that afternoon. One described the head wound as “tangential”. I take that to mean that it went along the right side of JFK’s head like a plough. And that is what the (undeveloped only later that day) Zapruder film shows. At the time of the head shot, JFK was slumped to the left , his head oriented left and slightly downward. A shot entering the right temple from the most often sited source, the “grassy knoll”, would have had to have made a 70 degree left turn to exit out the right-rear of the skull. Yet there was no damage to the left side of the skull that the reaction forces to such a turn would have generated. If the bullet and ejected brain matter exited the right-rear of the skull, why were only the motorcycle escorts on the left side of the limousine splattered with debris? Why was a large skull fragment found in front of and to the left of where the limousine was located at the time of the head shot?

I suspect there was a conspiracy in the planning and the cover up. And there may well have been a second shooter. A reenactment of the throat shot shows it exiting from JFK’s chest rather than throat, implying a shot from an elevation much lower than the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository.

I think all shooters were firing from behind, especially if they planned to pin it on a lone nut firing from behind. Otherwise, you need a cast of thousands to alter all the evidence.