Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

He knew it was coming.

The way a storm announces itself in the bones.

The way a man knows the land he’ll die on.

Lyndon Baines Johnson had already faced the thing most men spend their lives avoiding: death. It had gripped his chest, dropped him to the bedroom floor of his Texas ranch, and whispered its terms.

He survived.

But not without consequence.

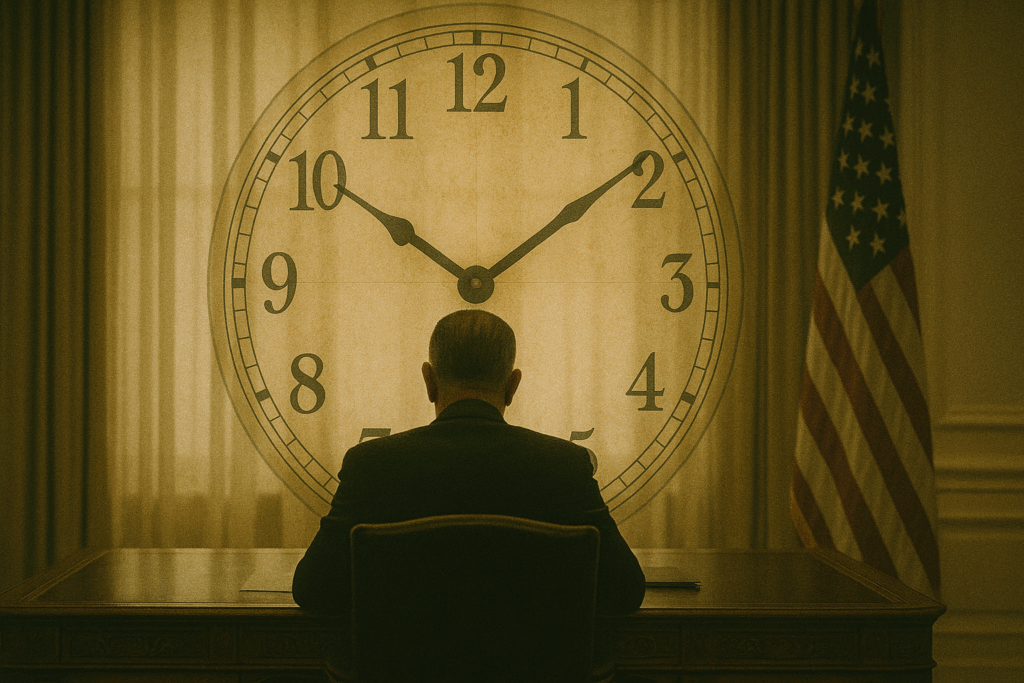

From that morning on, he ruled with the urgency of a man racing the clock. Not metaphorically — literally. A damaged heart beat beneath his ribs, erratic and scarred, every contraction a roll of the dice. He could feel it. Hear it. Sometimes, fear it.

And the world didn’t know.

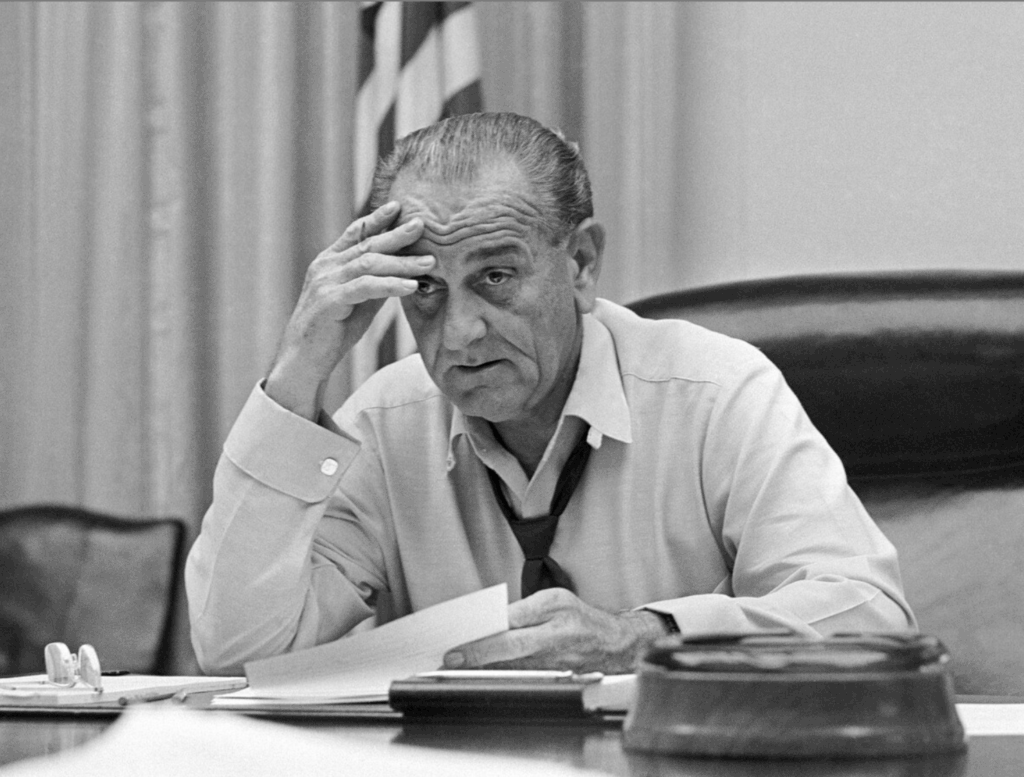

What they saw was the legend: the towering Texan who passed the Civil Rights Act, launched the Great Society, escalated Vietnam. The man who bent senators with a stare, signed bills with a flourish, and filled a room like a thunderhead.

But behind closed doors, he wheezed. He paced. He woke in the middle of the night convinced he was dying. He called his doctors at three in the morning, whispering fears they were not allowed to repeat.

He governed from behind a curtain of power — and a veil of denial.

And somewhere in the wings, a small cadre of physicians played their part. Not just treating the President, but preserving the illusion that nothing was wrong.

This is the story of Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidency.

But also the story of his heart.

And the men who kept it beating — until they couldn’t.

Chapter 1 – The Day the Clock Started Ticking

A Damaged Heart

The scream never came.

Just a sharp, involuntary gasp — the kind that seemed to rip loose from somewhere beneath the sternum — and then silence.

It was August 2, 1955, and the Texas morning was already pressing its heat against the walls. In the bedroom of the ranch house, ceiling fan turning slow as an old clock, Lyndon Baines Johnson reached for another paper from the stack on his bed — and froze. The words blurred. A deep, vise-like pain clamped across his chest, as if the air itself had turned to iron. His left hand went to his breastbone — not in thought, but in reflex — and stayed there.

Then his knees buckled.

The fall was sudden but heavy, like timber giving way. Bare feet slapped the carpet once before he crumpled. The lamp on the nightstand rattled. A half-finished Camel tipped in the ashtray, trailing a thin column of smoke toward the ceiling. Papers slid from the bed and fanned across the floor.

Lady Bird heard the thud, a sound that didn’t belong in the rhythm of a quiet house. She ran in and stopped short. Her husband was sprawled on the floor, lips edged in blue, a smear of blood where he’d bitten his tongue. She dropped to her knees, calling his name, one hand on his shoulder as if she could shake him back.

The ambulance swallowed him, the doors clanging shut on the hot white morning. Inside, the air smelled of metal, sweat, and gasoline. The siren began to wail, its rising pitch the only proof they were moving.

Johnson’s breathing came in ragged bursts, as if each inhale was an argument. The medic leaned close, cuff at the ready, eyes on the pale rise and fall of the man’s ribs. Johnson turned his head, his voice a scrape of gravel:

“Don’t let them pronounce me dead on the side of the road.”

The medic said nothing, only kept one hand near the cuff, the other near the morphine.

The siren cut through the heat, pulling them toward Waco, toward a hospital that had no cath labs, no troponin tests, no telemetry — only oxygen, morphine, ice packs, and the thin hope that the damage wasn’t already beyond repair.

By the time the ambulance doors swung open, the heat outside was a wall. Nurses rushed forward, their starched whites almost blinding in the glare. Johnson was lifted, the stretcher legs snapping open as they rolled him inside.

The air in the emergency bay was cooler, but thick with disinfectant and the faint tang of ether. Somewhere in the corner, a clock ticked with the kind of authority only a man fresh from death notices. A doctor leaned over him, listening hard to the rasp of each breath, one eye on the second hand. Leads were clipped to damp skin; paper began to curl out of the ECG machine.

The waveform was jagged, unmistakable — tall, tombstone-shaped peaks blazing across the paper. It told its own story: a heart under siege, muscle dying in real time, and a man who would never be quite the same again.

The ECG showed sharp ST-segment elevation across the anterior chest leads — the classic pattern of a large anterior myocardial infarction. The culprit was almost certainly a complete blockage of the left anterior descending artery, the “widow-maker,” cutting off blood supply to the front wall of his heart. The damage was extensive, irreversible, and in 1955 untreatable except with rest, morphine, oxygen, digitalis, and hope. Without reperfusion therapy, the prognosis for such an anterior MI was grim. Johnson survived, but his heart would never be whole again — and every doctor in that room knew it.

The Long Silence

For six months, Lyndon B. Johnson all but vanished.

The man who once ran the Senate like a live wire—every call answered, every favor collected—was now a patient. His world had shrunk to pill bottles, pulse counts, and the slow drone of a ceiling fan.

August 25, 1955 – Washington, D.C.

Two weeks after the collapse, a leaner Johnson faced the cameras. The late-summer heat shimmered, microphones jutted forward like bayonets.

Reporters said he was “recovering nicely.”

Johnson said little. In truth, he felt entombed.“I feel like I’ve been buried alive,” he told an aide. “I’m breathing dirt.”

He counted his heartbeats until the numbers blurred, fixated on his father’s death at sixty, underlined grim medical articles about recurrent infarcts. His doctors — Crismon, Hurst, and consultants like Paul Dudley White — fed him digitalis, sedatives, and the cold counsel of rest.

The ranch had been his exile, but exile sharpened him. He read reports in bed, scribbled notes in margins, and kept his ambition under a blanket of quiet. Visitors left thinking he was fragile. He wanted it that way.

One night, watching the ceiling fan turn its lazy circles, he told Lady Bird:

“Sixty-four. That’s all I’ve got.”

It wasn’t just a number. It was a deadline.

The plotting would last for months. The comeback would last for years.

And when he finally walked back onto the Senate floor, it wasn’t as a survivor.

It was as a man who intended to spend the rest of his borrowed time like it was stolen.

Back to the Hill

By 1957, he wasn’t just back in Washington.

He came in like a weather front.

The first Civil Rights Act since Reconstruction — carved, sanded, and muscled through a Senate that had buried such bills for decades. Johnson counted votes the way a card sharp counts chips, never losing track of the pile. He didn’t waste persuasion where arithmetic would do.

In committee rooms, he loomed. In hallways, he blocked the light. He carried digitalis in one pocket, sedatives in another, and still checked his pulse in mid-conversation, as if daring his heart to keep up.

“That’s where they almost got me,” he’d say, tapping his chest. “But not yet.”

The years between his heart attack and 1960 had turned him harder. The convalescent had learned patience — not the gentle kind, but the kind a hunter learns lying in tall grass. He cultivated alliances, settled scores, and kept his name in the column of “serious men” in every political conversation.

Then came the 1960 Democratic Convention.

John F. Kennedy — young, northern, Catholic — needed a southern Protestant with influence in Congress and strong support in the South. Johnson understood this before Kennedy even asked. He also knew the vice presidency was a limited role, but it was the only path that could take him directly to the Oval Office.

He took it. Told himself it was the surest path to the only job worth dying for.

Three years later, the motorcade would slow in Dallas’s Dealey Plaza, and gunfire would split the air

Chapter 2 – Borrowed Minutes

The Oath

November 22, 1963. The clock found him in Dallas.

On the tarmac at Love Field, the air was bright and brittle. By the time they reached Air Force One, it had turned stale with shock. The cabin was crowded, the hum of the engines muffled by the press of bodies and the gravity of what had just happened.

Johnson’s hand rose; beside him, Jackie Kennedy stood in her blood-stained suit, silent witness to the transfer of power. The oath came low and grave, each word caught between duty and disbelief.

Rear Admiral George Burkley stood just off Johnson’s shoulder, eyes fixed not on the Bible but on the man holding it. He knew Johnson’s heart had failed once before, and the strain of this day was testing it again.

When the ceremony ended, the plane lifted, Texas shrinking to a brown quilt beneath them. Burkley wrapped the cuff around Johnson’s arm. The numbers climbed.

Johnson grinned. “Told you, Doc — my ticker’s still running.”

Burkley didn’t smile back.

Contact Sport

Back in Washington, Johnson moved like a man with borrowed minutes and a country to spend them on.

The “Johnson Treatment” wasn’t a story; it was an anatomy lesson. Torso leaning in, breath on the cheek, baritone filling the air. He didn’t persuade; he surrounded.

The Civil Rights Act bent to his will. The filibuster broke. Then came Medicare. Medicaid. Education reform. Laws fell like dominoes in a legislative blitz that felt more like battlefield triage than politics.

The price showed in his chest. His heart was already slowing him down, but Johnson treated each day like a bill that had to pass before midnight. Some nights, he left the Capitol with a win in his pocket and a fist pressed under his ribs, leaning back in the car seat as if trying to push the pain away.

Still, the next morning, he was back — jacket off, tie loose, eyes locked on the next piece of history to drag across the finish line.

Funerals Without Caskets

His early political kills as President didn’t need bullets. They happened under buzzing fluorescents, the air sour with burnt coffee and the faint metallic tang of paperclips and filing cabinets.

A chairman who crossed him saw his highway bill disappear overnight — no explanation, just a polite smile the next time Johnson walked past him in the corridor. A Southern ally who hesitated on civil rights found his federal contracts suddenly gone.

Johnson buried opponents in the quiet paperwork of power — hearings never scheduled, nominations left to yellow in folders, phone calls that simply stopped being returned.

He knew the choreography: a pat on the back, a friendly grin, and then the political equivalent of a slow burial in wet cement. The victim always realized it too late.

Funerals without caskets.

At night, another Johnson emerged — stripped of tie and jacket, sock-footed, pacing the residence with a Scotch in one hand and antacids in the other. Sometimes the phone to Burkley was about chest tightness. Sometimes, about a headline, he couldn’t stop rereading. Sometimes both.

More than once, after a day of quietly gutting a rival’s career, he would stand alone in the Oval Office, thumb pressed into his sternum as if testing the hinge on a door. He’d count the beats, slow at first, then faster, until the rhythm seemed wrong. That was when he’d reach for the little brown bottle in his desk drawer.

The fear was real, and the numbers never lied.

The Prince and the Texan

Bobby Kennedy watched from down the hall — Attorney General, keeper of his brother’s legend, and Johnson’s most intimate enemy.

Their relationship was a duel fought entirely indoors.

Bobby thought Johnson crude, opportunistic, unworthy of the office he now occupied.

Johnson thought Bobby a sanctimonious prince who had inherited his power, never paid the price of earning it, and understood politics only in the abstract, never in the blood.

Their meetings were brittle theater. Bobby spoke in clipped, lawyerly sentences. Johnson responded in long, rolling drawls that could sound like warmth but were often a trap.

“Mr. President,” Bobby once said, “the country needs less force and more faith.”

“The country,” Johnson replied evenly, “needs results. Faith doesn’t pave a road.”

Sometimes, after those exchanges, Johnson would step into the hallway and rub his chest — slow, as if testing for tenderness. Burkley noticed it more than once: the faint wince, the subtle reach for the inside pocket where the nitroglycerin lived.

The friction was personal, but it had a cost in policy. Allies had to choose sides, and the White House corridors seemed to hum with whispered loyalties. Johnson did not forgive easily; Bobby did not forget at all.

Meanwhile, Burkley, Hurst, and Crismon formed a quiet medical cordon around the President. Digitalis in the desk drawer. Reserpine in the nightstand. Nitroglycerin within arm’s reach at all times. Sedatives when sleep refused him.

BP on bad days: 190/110.

Resting pulse: triple digits when the news was bad — and Bobby’s visits always seemed to make the news bad.

Weight: climbing with each banquet and midnight bowl of chili.

“Slow down,” Hurst urged.

“What for?” Johnson said. “The country’s not slowing.”

The Daisy Ad

In the 1964 presidential election, Johnson crushed Barry Goldwater in one of the most lopsided victories in American history. He won 61% of the popular vote, 486 electoral votes, and left Goldwater with only six states.

The “Daisy” ad aired once and never needed to again; its shadow lingered over every ballot cast.

On September 7, 1964, the Johnson campaign aired a single television commercial that became the most infamous in American political history. A young girl counts the petals of a daisy in a sunny field — her voice replaced by a missile launch countdown. The screen fills with a nuclear explosion as Lyndon Johnson warns of the stakes in the upcoming election. It never mentioned Barry Goldwater by name, but the message was clear: vote for Johnson, or risk annihilation.

The mandate was undeniable, and Johnson spent it fast. The Voting Rights Act was signed within months, locking his name into the new civil rights era. Then came the Great Society — Medicare, Medicaid, education aid, housing reform — legislation fired off like artillery from a desk where nitroglycerin was always within reach.

But as the laws stacked up, so did the briefings. At first, Vietnam was just a folder on the edge of the desk — a few clipped lines about troop counts, air strikes, casualties. Then the folder grew thick. The maps grew darker. The jungle inched closer, winding its way into Situation Room meetings, into late-night calls, into the pulse in his neck.

And somewhere in Southeast Asia, a calendar page turned — toward Tet, and the offensive that would tear through everything.

Chapter 3 – The War Inside Out

The Shattering

Tet didn’t just hit cities; it hit certainties.

The maps in the Situation Room were supposed to contain the war. Lines drawn in grease pencil, arrows showing where the enemy would go — where they were allowed to go. But in the last days of January 1968, the maps stopped making sense. Viet Cong fighters were in Saigon, in Hue, in the U.S. Embassy compound. The arrows no longer matched the reality on the ground.

The morning briefings were brittle affairs. Johnson leaned over the table, hands braced on its edge, staring at photographs so grainy they looked like bad memories. Walter Cronkite went on television and told America the war couldn’t be won. In the Cabinet Room, no one said it that plainly — but Johnson could see it in their eyes.

The war was no longer an abstraction in briefing papers. It was a shadow in the room, growing thicker every day.

That shadow followed him home. The pain behind his sternum came more often now, sometimes sharp, sometimes a slow press that made him loosen his tie. The nitroglycerin tablets dissolved under his tongue with a bitter taste he no longer noticed. He could still work the phones deep into the night, but when he finally set the receiver down, the silence felt heavier than the war itself.

The Second Body Count

By ’67, Washington had its own casualty list — political, not military.

A governor who questioned troop levels found his federal funding “temporarily suspended.” A party donor who flirted with Bobby Kennedy saw his pet legislation vanish in markup. Johnson tracked these as closely as casualty numbers from the field, each defeat or removal another entry in a ledger he kept in his head.

The same precision he once used to count votes for the Civil Rights Act now went into counting who had crossed him and what it would cost them.

But the strain was no longer invisible. He’d pause mid-sentence in a meeting, thumb pressed to his breastbone, waiting for the moment to pass. Sometimes he’d light a cigarette he shouldn’t have touched, draw in one drag, and stub it out before anyone could comment. The taste of metal lingered anyway.

At night, the phone calls to Burkley grew more frequent. “Feels tight,” he’d say. Burkley would listen, weigh the risk, and tell him to rest — knowing Johnson would be in the Oval Office by morning.

Collision Course

Bobby Kennedy stopped circling and stepped into the open. First as conscience, then as contender.

Their encounters were no longer whispers in hallways; they were staged duels. Cameras caught the angles — Bobby upright, chin tilted; Johnson looming, eyes narrowed, voice low enough that only Bobby could hear.

“Mr. President,” Bobby said during one tense exchange, “the country needs less force and more faith.”

“The country,” Johnson replied evenly, “needs results. Faith doesn’t pave a road.”

These weren’t debates; they were skirmishes in a war of succession neither could win outright without destroying the other. Staffers learned to read the aftermath — Bobby walking out fast, jaw tight; Johnson rubbing his chest in small circles, breathing through his nose.

Behind closed doors, Burkley kept the Librium and nitroglycerin close. The mornings brought angina on the stairs; the nights brought arguments with ghosts — JFK’s shadow at the head of the table, the war ledger open in front of him.

The Folded Decision

By early ’68, even victories felt hollow. The solitude after meetings stretched longer; the pauses between sentences widened. Johnson still knew every lever of power, but the machinery was grinding down — in Congress, in the war, and in his own body.

March 31. The speech began with troop ceilings and bombing halts. On the desk in front of him lay a sheet of paper folded once, the words inside known only to him and Lady Bird.

She could hear it in his breathing before he reached the final page — a slow, deliberate cadence that wasn’t fatigue but something closer to resolve.

“Accordingly…”

He looked down at the folded paper, then out toward the camera’s dark glass.

Chapter 4 – The Last Card

“…I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

For a moment, there was only the whir of the television cameras and the faint rustle of paper. Then the sound hit — a low collective exhale across the country, from kitchen tables to bar counters to dorm rooms where students had been chanting outside the White House only hours before.

In living rooms, people turned to one another and asked, Did he just quit?

In hospital lounges, doctors and nurses nodded to themselves. They’d been watching him age in real time. They knew what it meant.

In the West Wing, aides stared at one another, unsure whether to clap or to start packing. The president had dropped his own future into a single sentence, then folded his hands as though nothing unusual had happened.

Bobby Kennedy heard it while campaigning in Indiana. No smile, no gloating — just a subtle narrowing of the eyes. For Bobby, Johnson’s decision didn’t erase the animosity; it simply moved the battlefield.

The speech had been the public face of the decision. The private one had been building for months — chest tightness that came sooner with each set of stairs, headaches blooming after minor confrontations, blood pressure that could crack glass. Burkley had warned him: Sir, the strain is writing its own ending.

The presidency wasn’t done with him, even if the campaign trail was. Outside, the streets were still burning. Half a world away, the jungle war was still chewing through lives and headlines.

And in the quiet of that night, Johnson knew one thing: the last card he’d just played would not be the last move he’d make.

Moments after announcing he would not seek re-election, Johnson sat for a brief photograph in the Oval Office. Shoulders squared, tie slightly loosened, the lines around his mouth deeper than they had been just an hour earlier. Reporters noted the strange mix in his expression — not triumph, not defeat, but something quieter. Relief, perhaps. Or simply the look of a man who had decided to stop racing the clock, at least in public.“I will leave this job, but I will not leave my country.”

Epilogue – The Ticking Man

History would remember the night he stepped away as an act of politics. Medicine knew better.

The 1955 heart attack had carved a line through his life, and everything afterward was lived on borrowed minutes. Each major bill, each foreign crisis, each bare-knuckle fight on the Hill had been paid for in silent currency — a racing pulse, a spike in blood pressure, a breath taken a little too late.

He had pushed past every warning, convinced that power, once in hand, should never be set down. Yet in the end, it was not an opponent or an election that made him fold. It was the quiet arithmetic of a body that had been warning him for years.

When Johnson left Washington in January 1969, the war still burned, the streets still roiled, and the Great Society was still half-built. At the ranch, away from the cameras, he slowed only in appearance. He chain-smoked, put on weight, and confessed to friends that he could feel the “hitchhiker” — his name for the damaged heart — keeping pace with him.

Four years later, on January 22, 1973, at the age of 64, the hitchhiker caught up. Lyndon Baines Johnson was found on his bedroom floor, a phone in his hand, trying to call for help. The heart that had outlasted political enemies, global crises, and its own massive injury finally stopped.

In the end, the clock that had started ticking in 1955 didn’t explode or shatter — it simply wound down, one final click in an empty Texas room.

Next in the Series

He was there when Johnson clutched his chest in ’55 — and when the oath was taken beside Jackie Kennedy’s blood-stained suit.

He’d checked the pulse of two presidents, one felled by an assassin’s bullet, the other racing a damaged heart.

Rear Admiral George Burkley knew the limits of medicine — and the danger of what happened when those limits met the demands of power.

The Heart of Power – George Burkley: The Doctor Who Knew Too Much

Previous:

Episode 1. The Heart of Power: When Metabolic Disease Entered the Oval Office – William Howard Taft

Episode 2. The Heart of Power: The Golf Course Heart Attack – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Episode 3. The Heart of Power: The Stroke That Silenced a Dream – Woodrow Wilson

Episode 4. The Heart of Power: Built To Stand, Bound To Fall – John F Kennedy

Episode 5. The Heart of Power: Where Strength Sat Still – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Episode 6. The Heart of Power: The Ride Into the Sunset – Ronald Reagan

Episode 7. The Heart of Power: The Enemy Inside – Richard M Nixon

📚 Sources & Further Reading

Biographies & Histories

- Caro, Robert A. The Years of Lyndon Johnson series. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. — Especially The Passage of Power and Master of the Senate for detailed accounts of LBJ’s political ascension and White House years.

- Dallek, Robert. Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961–1973. Oxford University Press, 1998. — Insightful on LBJ’s presidency, health issues, and personal struggles.

- Beschloss, Michael R. Taking Charge: The Johnson White House Tapes, 1963–1964. Simon & Schuster, 1997. — First-hand look into LBJ’s private conversations after assuming the presidency.

Medical Context

- Braunwald, Eugene Evolution of the management of acute myocardial infarction: a 20th century saga. The Lancet, Volume 352, Issue 9142, 1771 – 1774. Link

Archival Material

- Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library — Oral histories, medical notes, and staff recollections related to the 1955 heart attack and presidential health. Link

- The Miller Center, University of Virginia — Transcripts of LBJ’s recorded phone calls and public addresses. Link

- National Archives and Records Administration — Photographs, flight manifests, and medical records where available.

Multimedia & Primary Footage

- The “Daisy” Ad (1964 Johnson Campaign).

- WFAA-TV Dallas. “Air Force One Swearing-In Ceremony.” Archival coverage of November 22, 1963.

Some portions of this article were developed with support from ChatGPT, an AI tool created by OpenAI. It was used to assist with research synthesis, narrative structure, and language refinement. All medical content, historical analysis, and editorial decisions were independently reviewed and finalized by the author.