Share this post:

Estimated reading time: 18 minutes

Smoke still curled from the wreckage at Pearl Harbor.

Across the Pacific, the dead were still being counted—some drowned in burning ships, others incinerated before they could lift a rifle.

In Washington, phones rang without rest. Advisers swarmed. The White House throbbed with urgency.

Through it all, Franklin Delano Roosevelt sat at his desk, calm but electrified. He had barely slept. He had smoked incessantly—through briefings, through silence, through sleep-deprived hours where every drag seemed to hold back the flood. One cigarette melted into the next, a slow-burning ritual of tension and resolve. The long ivory holder rarely left his mouth. He puffed in silence, exhaled strategy. He was already composing history.

Now it was morning.

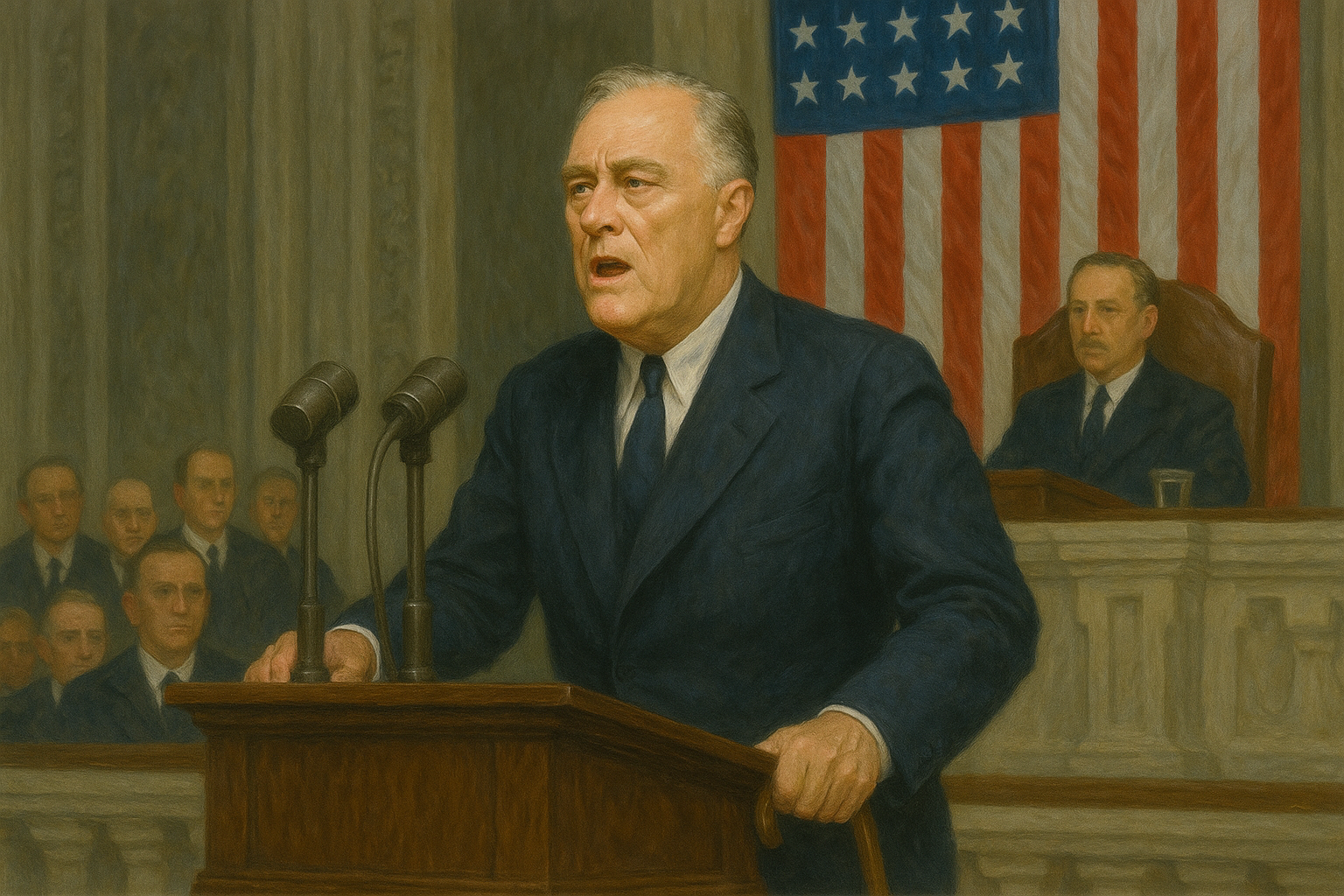

He entered the House chamber—packed with lawmakers, reporters, and the gravity of a world suddenly at war—slowly, methodically, as he always did. An aide at his side. His legs, stiff and lifeless, encased in ten-pound steel braces, swung forward with each pivot of the hips. He gripped a cane in one hand, the arm of his son James in the other. Every step was a battle between dignity and gravity.

He reached the lectern, pulled himself upright, and paused. The room fell silent. He leaned forward, inhaled quietly, and began:

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy…”

His voice was steady, deliberate, resolute. It echoed through the Capitol and across the nation’s radios, sinking deep into the marrow of an anxious public.

War had arrived on two fronts. The world was unraveling. But the president—though unable to stand unassisted—stood.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt had long ago lost the use of his legs, the result of a paralyzing illness at 39. But his authority, his voice, and his unshakable calm only grew. What the public didn’t see—or chose not to—was the deeper cost. Beneath the public strength was a private, slow-motion collapse. He smoked constantly. His blood pressure climbed year after year. The arteries that fed his heart and brain were thickening, stiffening, narrowing. The man who steadied a nation was, himself, running out of time.

This is the story of how he endured—not by denying his burdens, but by outpacing them. How a man governed through illness, pressure, and concealment, yet never let his faltering body diminish the authority he wielded or the faith he inspired.

And yet, in the end, the toll could no longer be hidden. In his final months, the disease was winning. His voice grew thinner. His face gaunter. The arteries he had pushed beyond their limits for years were quietly closing in.

To understand how a man so outwardly strong could slowly unravel from within, we must return to the beginning—before the presidency, before the war—back to a summer on Campobello Island, and the illness that nearly ended his life before it truly began.

The Illness That Struck a Rising Star

The summer of 1921 should have been a season of triumph.

At 39, Franklin Roosevelt was politically ascendant. After serving as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in World War I, he was eyeing higher office. He had charisma, pedigree, and an unshakable belief that his future was assured.

But his personal life was strained. His marriage to Eleanor Roosevelt had been shaken by his affair with her social secretary, Lucy Mercer. Eleanor discovered the relationship in 1918 and threatened divorce. Franklin chose politics. The marriage endured—but its emotional foundation cracked. They remained partners, but in name and duty more than intimacy.

Years later, Lucy would quietly return, visiting him in private, even in his final days at Warm Springs. Eleanor tolerated it, but never truly forgave it.

Still, Roosevelt brimmed with energy that summer. He sailed. He swam. He chased his children along the cliffs of Campobello Island. Until, suddenly, he couldn’t.

One evening, after a day on the water, he felt a chill. By the next morning, one leg was weak. Within two days, both were immobile. Pain surged through his back. His bladder stopped working. He could no longer stand. The man who had moved so effortlessly through the world was trapped inside his body. Doctors cycled through explanations: a spinal clot, then lumbago, then finally—poliomyelitis.

Polio. The diagnosis was grim. His lower body was paralyzed. Recovery, if any, would be partial. The world he had built—of motion, power, and political ascent—seemed to vanish overnight.

Friends fell silent. Colleagues offered kind words, then stepped back. A disabled man in public life? It was unthinkable. Roosevelt was devastated. He wept, raged, denied. But beneath the despair, something in him hardened. He would not be left behind.

Eleanor watched closely. She later said her husband had faced two great trials: the loss of his legs, and the decision to rise again. She encouraged him, shielded him—and in doing so, began discovering her own voice. Much of that transformation unfolded not on windswept Campobello, where illness first struck, but at Hyde Park—their family estate in upstate New York. There, in the quiet months of convalescence, her public activism, her moral clarity, and her political confidence began to take shape.

Roosevelt began intensive rehabilitation. At home, he endured massage, stretching, and painful daily exercises. Later, in Warm Springs, Georgia, the buoyant waters allowed him to mimic walking. He believed—perhaps irrationally—in recovery. He learned to crawl, to transfer, to swing his legs forward with his hips. His body did not return. But his will never left. And neither, in time, did Eleanor.

Yet even the illness that redefined his life would, decades later, come under scrutiny. It shaped his path to power, but what if the doctors had been wrong?

As Roosevelt pressed forward, one quiet question remained: what, exactly, had happened to him that summer?

Polio—or Was It?

In 1921, the doctors said it was polio. And for more than eighty years, no one seriously questioned them. But in 2003, a team of researchers took another look—and came to a startling conclusion: Franklin D. Roosevelt might not have had polio at all.

Their review, published in the Journal of Medical Biography, pointed to a different culprit: Guillain–Barré syndrome, or GBS.

So what’s the difference? Polio is a viral assassin. It invades the body, targets the spinal cord, and destroys motor neurons—often in a patchy, uneven way. One limb might be limp while another stays strong. Pain is rare. Sensation is usually preserved. And in 1921, polio was infamous—a disease that haunted summer camps, schoolyards, and swimming holes.

Guillain–Barré, by contrast, is an autoimmune ambush. It usually follows an infection. The body turns against its own nerves. Weakness starts in the legs and climbs upward. Both sides are hit. Pain is common. So is numbness. It’s rare, unpredictable—and far less well known at the time.

Now consider Roosevelt. His paralysis was symmetric—both legs went, and his upper body was affected too. That’s GBS. He had severe pain and sensory changes—again, classic GBS, not typical polio. His fever disappeared before the paralysis worsened—strange for polio, but not for GBS. And he was 39 years old—well past the usual age for first-time polio.

But there’s no smoking gun. No spinal tap. No nerve studies. Just a timeline and a list of symptoms. So was it polio? Maybe. It was the best guess in 1921. The doctors did what they could with what they had.

But if the 2003 paper is right—and it might be—then history’s most famous polio patient may not have had polio at all.

Whatever the name of the disease, the damage was done. Roosevelt would never walk unaided again. But he could rise—and that became the next chapter. What followed wasn’t recovery in the medical sense. It was something harder, something rarer: reinvention.

Rebuilt, Not Restored

What polio destroyed, Roosevelt rebuilt by sheer force of will. At Warm Springs, he wasn’t just a patient—he became a benefactor and community builder. He bought the facility, invited others with paralysis, and created a sanctuary of resilience.

His personal routine was rigorous. In the pool, he could simulate walking. On land, he trained his upper body to perform the work of his legs. He practiced using a cane and swinging his hips with locked knees—a painstaking technique that allowed him to move short distances. It was never effortless. It was never painless. But it looked, from a distance, like movement.

And so began his second ascent.

In 1928, Roosevelt accepted the Democratic nomination for Governor of New York—a bold and risky move. It wasn’t just a return to politics; it was a reintroduction to a nation that hadn’t seen him in public life since illness had struck. He understood the stakes. Every appearance was meticulously planned. With braces hidden beneath tailored suits and aides discreetly supporting him, he stepped back into the spotlight—smiling, composed, and determined to control the narrative.

He won the election. Narrowly, but unmistakably. As governor, Roosevelt leaned into progressive reform. He confronted labor issues, expanded social services, and proved himself a pragmatic and creative leader. More importantly, he returned to public life with a renewed empathy for those who struggled—whether from poverty, disability, or despair. His time in the political wilderness had reshaped him.

Then came 1929. The crash. The panic. The unraveling. As the Great Depression swept across the country, Roosevelt’s star began to rise. By 1932, with Herbert Hoover’s administration paralyzed and breadlines growing by the day, Democrats turned to Roosevelt as the man who could lead from the ashes.

He campaigned for president on “a New Deal for the American people,” and the country listened. He traveled by train, delivering fiery speeches from the rear platforms. Always standing—always gripping something—always smiling. He projected energy and hope. The details of how he moved from car to podium were never discussed.

The illusion held. He won in a landslide.

In the spring of 1933, he arrived in Washington as the 32nd President of the United States—only the second to serve in a wheelchair, though the public was rarely shown that reality. The banks were collapsing. Farmers were destitute. The nation was afraid. And yet here was this man, smiling through the radio, declaring:

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

His presidency had begun.

The Illusion of Strength

Franklin Roosevelt understood the power of an image—and the danger of the wrong one.

Once, he had been tall and athletic, striding confidently through crowds, sailing, riding, shaking hands from railcars. After paralysis, motion became a risk. A stumble, a pause too long, the wrong angle—any of it could shatter the illusion. So he rebuilt his public life not just on policy, but on choreography. He didn’t hide the fact that he’d had polio. He even joked about it sometimes. But he never let the country see what it had done to him.

Photographers were warned not to capture him walking—or being helped to walk. The few who tried were intercepted by Secret Service agents who didn’t just guard the president—they guarded the image of strength. Of the thousands of photos taken during his presidency, only a few show him in a wheelchair. Most were snapped in defiance, or by accident.

Roosevelt knew that Americans—still reeling from economic collapse—couldn’t afford to see their leader as frail. They needed certainty, not struggle. So he gave them strength in silhouette: the broad shoulders, the confident wave, the beaming smile. The legs weren’t shown. The effort wasn’t visible. Only the outcome mattered. This wasn’t vanity. It was discipline.

He waved from train cars. He held press conferences with his trademark cigarette holder tilted at a jaunty angle. He radiated cheer, even when exhausted. Reporters who traveled with him sometimes glimpsed the reality—the naps between stops, the strain beneath the smile—but they didn’t write about it. Not because they were deceived, but because they understood the unspoken rules. It was a different time. The presidency still had a private side. Illness didn’t make headlines. Appearances mattered, but they weren’t dissected. And Roosevelt used that to full advantage.

In 1933, when FDR took office as the economy was in ruins. Banks were closing. Families were hungry and afraid. He met the moment not with spectacle, but with sound. His fireside chats, broadcast from the White House into homes across the nation, brought reassurance where none had existed. He explained complex policy in plain language. He offered calm amid panic. His physical presence was absent—but his voice filled the silence of every living room.

While others might pace the floor, Roosevelt sat and planned. He was methodical, intense, unshakable. His New Deal reshaped the country. Social Security, financial reform, jobs programs—each born from the mind of a man who had learned to wait, adapt, and endure.

In 1941, after Pearl Harbor, the war president emerged.

The War He Didn’t Want—And the World He Tried to Save

Franklin D. Roosevelt did not come to office as a war president. Quite the opposite—he promised to keep America out of war. Throughout the late 1930s and into his 1940 re-election campaign, he walked a political tightrope.

Hitler marched through Europe. Japan carved its empire across Asia. But the American public, haunted by World War I, wanted no part of another foreign war. Roosevelt reassured them: “Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.”

But privately, he prepared. He expanded the Navy, approved the Lend-Lease Act, and traded destroyers for bases with the British. He answered Winston Churchill’s calls for help. Together, before the U.S. had fired a shot, they were already plotting the architecture of Allied victory.

Roosevelt admired Churchill’s defiance. Churchill respected Roosevelt’s restraint. Their alliance—equal parts strategy and friendship—would shape the course of history.

And then came Pearl Harbor. In a single day, isolationism collapsed.

Roosevelt declared war on Japan. Days later, Hitler declared war on the United States. The tightrope was gone. Now FDA led a global crusade. Despite his failing health and paralyzed legs, Roosevelt traveled to meet the men who would decide the world’s future: Churchill and Stalin. At Casablanca, Tehran, and Yalta, he appeared gaunt but composed—wrapped in his cape, seated but commanding.

With Stalin, Roosevelt’s instincts were hopeful. He believed the Soviet leader could be tempered—woven into a cooperative postwar order. Some called that naïve. Others, necessary.

Hitler saw it differently. To him, Roosevelt wasn’t just another Allied leader—he was the ideological architect of Germany’s destruction. In private rants, Hitler spat venom, calling him “the crippled Jew-lover,” “a devil in a wheelchair,” and “the real brains behind the Allied conspiracy.”

By 1942, reports of mass executions were reaching Washington with growing clarity. Jewish leaders pleaded for action—for the bombing of rail lines to Auschwitz, for looser immigration quotas, for the creation of safe havens. But the administration hesitated. Caution prevailed over conscience.

Domestic politics, antisemitism, and fears of being seen as fighting “a Jewish war” shaped policy more than moral urgency. Refugee ships were turned away. Visas languished in bureaucratic limbo. The quotas remained shamefully underfilled. It wasn’t until 1944, under mounting internal pressure, that the War Refugee Board was established—too little, too late for millions.

Roosevelt spoke often of freedom, human dignity, and the evils of Nazism. But on this front, his actions fell short of his ideals.

Still, he looked beyond the war. He envisioned a postwar order built on cooperation, not conquest—a world governed not by empires, but by law. He helped lay the foundation for the United Nations: an imperfect but enduring attempt to bind nations together in peace.

It was a dream he would not live to see.

By early 1945, victory was in sight—but Roosevelt was fading. At Yalta, he appeared gaunt and frail, his voice barely carrying the weight of his words. The toll of war, unrelenting stress, and years of silent disease had caught up with him. He was leading the final push against fascism while fighting a quieter battle of his own—one his body was losing. He died two months later, before Germany’s surrender, leaving behind a world he had helped remake, but would never see reborn.

The Final Campaign

By 1944, Franklin D. Roosevelt had been president for over 11 years. No American had ever served so long. No president had carried so much weight—economic collapse, war across two oceans, and the burden of being the world’s democratic anchor.

And by now, it showed. He had grown thin. His cheeks were hollow. The eyes that once dazzled a nation had dulled. Friends whispered that he looked like a ghost. Aides spoke of his fatigue in guarded tones. His doctors, though alarmed, said little publicly. He was dying—and almost no one knew.

Roosevelt suffered from severe, long-standing hypertension. His blood pressure routinely soared above 200. He had periods of breathlessness, swelling, and growing fatigue. But these signs were hidden from the public, and even many in his own administration.

Admiral Ross McIntire, the president’s physician, repeated a calming line: “The President is in excellent condition for a man of his age.” It was far from true.

By 1944, his heart was failing. He showed signs of congestive heart failure and likely small strokes—his speech sometimes slurred, his energy faltering.

Dr. Howard Bruenn, a cardiologist quietly added to the team, understood how grave it was. But secrecy held. And still, Roosevelt smoked. The cigarette holder rarely left his hand. Despite warnings, despite labored breathing and declining function, he continued—lighting one cigarette with the embers of the last. Whether habit, comfort, or quiet rebellion, it became a signature of his decline.

Yet Roosevelt pressed forward. The Democratic Party was uneasy. Could he survive a fourth term? Could he even finish it? Roosevelt dismissed their doubts. “I owe this to the country,” he said. “I owe it to the boys over there.”

And so he ran again—carefully, sparingly, leaning on Eleanor, radio, and reputation. He won handily. To voters, he still represented stability. They saw the familiar voice, the steady hand. What they didn’t see—what no one was allowed to see—was how close he was to collapse.

At Yalta in February 1945, it became undeniable. Roosevelt looked drawn, his head bobbing under its own weight. Churchill worried aloud. Stalin, ever blunt, reportedly said: “Roosevelt will not live long.”

Still, he led the meetings—drafting the postwar world between naps and failing pulses. Two months later, at Warm Springs—the place where he had once rebuilt himself—Roosevelt sat for a portrait. Halfway through, he raised his hand and murmured, “I have a terrific headache.” Moments later, he collapsed.

At 3:35 p.m. on April 12, 1945, Franklin Delano Roosevelt died of a massive cerebral hemorrhage. He was just 63 years old—not elderly by modern standards, but his cardiovascular system was decades older, worn down by relentless hypertension and years of heavy smoking.

Eleanor was in Washington. When the news came, she flew to Georgia. A reporter asked what the nation should do now. She answered softly: “The story is over.” But she knew it wasn’t. She would carry it forward, in grief and in purpose. Across the country, silence followed. Radios paused. Shops closed.

For many Americans, Roosevelt was the only president they had ever known. His death felt not like the loss of a man—but the end of an era.

Vice President Harry Truman took the oath that evening. And the unfinished portrait remained on the easel. But even as he passed, the question lingered: What, exactly, had Roosevelt shown us about strength?

Strength Redefined

He never stood unaided. He never walked the White House lawn. He never marched beside his generals. But Franklin Delano Roosevelt redefined what it meant to lead—not through motion, but through momentum.

In an age that worshipped strength, he governed from a chair. His power wasn’t in posture—it was in presence. His voice reached where his body could not: into kitchens, across oceans, into the hearts of people grasping for hope.

He didn’t dominate rooms. He anchored them.

The illusion of vitality wasn’t vanity. It was protection. He hid his paralysis to preserve public confidence. He knew symbols mattered. So he became one. But the illusion wasn’t the source of his strength. The cost was. He governed through pain, pressure, and decline.

His blood pressure soared. His heart weakened. His body gave way. But he pressed forward—not for pride, but because the work demanded it.

Through depression and war, through four terms and mounting illness, he absorbed blows—political, personal, physical—and kept going. When he died, America didn’t just lose a president. It lost its anchor. Roosevelt’s legs failed him. But he showed a nation how to stand—through fear, through fire, through silence.

Strength, he proved, isn’t stride. It’s direction.

Next in Series

He built a presidency on performance and poise. But the clarity behind his gaze began to dim long before the world was ready to see it.

In Episode 6, we turn to Ronald Reagan — a leader who radiated optimism and command, even as memory quietly unraveled behind the scenes.

With charm, instinct, and carefully managed appearances, he held the stage — while the script slowly slipped from view.

Coming soon:

The Heart of Power – Ronald Reagan: The Ride Into the Sunset.

Previous:

Episode 1. The Heart of Power: When Metabolic Disease Entered the Oval Office – William Howard Taft

Episode 2. The Heart of Power: The Golf Course Heart Attack – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Episode 3. The Heart of Power: The Stroke That Silenced a Dream – Woodrow Wilson

Episode 4. The Heart of Power: Built To Stand, Bound To Fall – John F Kennedy

Sources & Further Reading

- Goldman AS, Schmalstieg EJ, Freeman DH Jr, Goldman DA, Schmalstieg FC Jr. What was the cause of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s paralytic illness? J Med Biogr. 2003 Nov;11(4):232-40. doi: 10.1177/096777200301100412. PMID: 14562158.

- Smith JE. FDR. Random House, 2007.

- Dallek R. Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Political Life. Viking, 2017.

- Freidel F. Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny. Little, Brown, 1990.

- Ward G. The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. Knopf, 2014.

- Winik J. 1944: FDR and the Year That Changed History. Simon & Schuster, 2015.

- Beschloss M. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler’s Germany, 1941–1945. Simon & Schuster, 2002.

- Black C. Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. PublicAffairs, 2003.

- Kershaw I. Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions That Changed the World, 1940–1941. Penguin, 2007.

- Noakes L, Pattinson J (eds.). British Cultural Memory and the Second World War. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Portions of this article were developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model by OpenAI, to help refine structure, language, and clarity while preserving the author’s voice and scientific integrity