Share this post:

Estimated reading time: 21 minutes

In the summer of 1921, in a dim and dusty laboratory at the University of Toronto, a young surgeon with failing prospects and a second-year medical student began tying off the pancreatic ducts of dogs. What they were after was elusive—unseen, unnamed, and possibly imaginary. What they found would change the fate of millions.

They called it “isletin,” an improvised term for a substance that would soon shake the world of medicine.

Over the next hundred years, insulin evolved from a crude pancreatic extract to a high-tech therapy—and from a medical marvel to a global flashpoint. It reshaped diabetes from a death sentence into a chronic condition, gave rise to billion-dollar pharmaceutical empires, and exposed deep fractures in healthcare systems worldwide. At every step, its story raised urgent questions about access, equity, and the meaning of scientific legacy.

The discovery was revolutionary, but the aftermath was anything but harmonious. The acclaim brought turmoil. What unfolded behind lab doors was a storm of fatigue, fractured loyalties, and contested glory.

This is the story of insulin—not just as a hormone, but as a mirror reflecting the best and worst of medicine. A discovery that saved lives—and exposed how fragile our systems can be when ethics collide with ambition.

📌 Summary: The Insulin Wars

- In 1921, a struggling surgeon and a medical student extracted a mysterious substance from dog pancreases. That substance—insulin—transformed diabetes from a death sentence into a manageable condition.

- The discovery was a scientific triumph but triggered years of conflict over credit, ethics, and ownership. The original research team fractured. A Nobel Prize split them permanently.

- The discoverers sold the patent for $1 to ensure universal access. But over the decades, insulin was turned into a multibillion-dollar product—protected by patents, manipulated by pricing strategies, and rationed by policy.

- Today, three companies control over 90% of the global insulin market. More than half the world’s diabetics struggle to afford or access the drug.

- This article explores how insulin became a symbol of medicine’s greatest promise—and its deepest failures.

- The story of insulin is not over. Whether it remains a breakthrough that serves the public—or a product that serves profit—depends on what we do next.

Act I: Discovery and Triumph

“The boy was five when it started. He had always been small for his age, but now he was shrinking—visibly. His cheeks hollowed, his ribs pressed through skin, and he cried at night from hunger.”

Stories like his were tragically common. In the years before insulin, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in a child meant near-certain death—one that unfolded slowly, painfully, and without remedy.

This dire reality drove Banting and Best into their summer lab experiment, chasing a cure through exhaustion and uncertainty.

The pancreas had entered the scientific spotlight decades earlier. In 1889, two German researchers, Minkowski and von Mering, removed it from a dog and observed the onset of polyuria, polydipsia, and glycosuria—the classic signs of diabetes. The connection was undeniable: the pancreas secreted something essential for controlling blood sugar. They didn’t know what it was, but saw what happened without it.

Fast forward to the 1910s, and the only treatment available was radical calorie restriction, a grim protocol championed by Dr. Frederick Allen at the Rockefeller Institute. He called it “the fasting cure,” but it was no cure at all. Allen’s patients were placed on a diet of clear broth, a few ounces of vegetables, and occasionally a bite of dry bread. Many lived a little longer—but barely.

One young girl, Elizabeth Hughes, the daughter of U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, was among Allen’s patients. She survived on fewer than 800 calories a day for over three years. Her weight dropped to 45 pounds (20 kg). She kept a diary describing the days as “quiet, hungry, and cold.”

The diabetic child became a symbol of modern medicine’s failure. Families sold possessions for a few more months. Doctors sent children home to die with dignity. At some clinics, including Joslin’s in Boston, mortality in juvenile diabetics approached 100% within a year of diagnosis.

And yet, behind closed doors in laboratories across Europe and North America, something was stirring. Researchers were chasing that mysterious pancreatic secretion. They didn’t know it yet—but they were closing in on a hormone. One that had been inside the human body all along. Waiting.

The Scribbled Idea That Changed the World

It came to him at 2 a.m. A sleepless night, a scribbled note, and an idea so improbable it seemed more like a fever dream than a scientific plan.

He scrawled the idea into his notebook: tie off the pancreatic ducts of a dog, wait for the exocrine tissue to degenerate, and then extract the residue. The theory was crude. But it was enough to propel him into history.

The handwriting was rough, and the logic was murky, but Dr. Frederick Banting—then an unknown orthopedic surgeon in London, Ontario—believed he had found a path to the cure for diabetes.

Banting wasn’t a diabetes expert. He was barely surviving as a medical lecturer. But something in a journal article had caught his eye: when the pancreatic ducts were tied off, the exocrine (digestive enzyme-producing) tissue degenerated, but the islets of Langerhans—tiny clusters of endocrine cells—remained. Banting believed he could isolate whatever secreted the mysterious sugar-regulating substance that had eluded scientists for decades.

He took his idea to J.J.R. Macleod, a Scottish physiologist at the University of Toronto. Macleod was skeptical. The idea was crude. The approach unrefined. But Macleod, perhaps out of curiosity-or pity—agreed to give Banting a lab, ten dogs, and a summer medical student named Charles Best to help.

From Dog 410 To Toronto General Hospital

That summer of 1921 would become one of the most storied in medical history.

In the steamy, makeshift lab, Banting and Best operated on dog after dog, tying off the pancreatic ducts and waiting for the tissue to degenerate. They harvested what they called “islet residue,” crushed it, and injected it into diabetic dogs.

The early results were chaotic. Infections, technical failures, and primitive equipment made the work grueling. But then came Dog 410.

Despite the dramatic name, Dog 410 wasn’t the 410th animal in the study—just a label, possibly borrowed from earlier numbering at the lab. Banting and Best worked with roughly 10–15 dogs that summer, though the chaos of handwritten logs and sleepless nights made it hard to track.

Dog 410 was diabetic—created by removing its pancreas entirely. It was dying, its blood sugar dangerously high. Banting and Best injected it with their crude pancreatic extract.

The dog perked up. Its blood sugar dropped. It lived.

Word began to spread. Macleod returned from summer break and, seeing the promise in the results, took greater interest. He brought in a biochemist, James Collip, to help purify the extract. The crude concoctions had been causing fevers and abscesses—but they were saving lives.

Then, in January 1922, the team faced their ultimate test: a human patient.

Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old boy with type 1 diabetes, lay dying at Toronto General Hospital. Weighing just 65 pounds (29 kg), he was near comatose when Banting’s team injected him with insulin. The first dose was impure—he developed an abscess. But twelve days later, they tried again, using Collip’s refined version.

It worked. His blood sugar dropped. He stabilized. And for the first time in history, a diabetic patient didn’t starve—he lived.

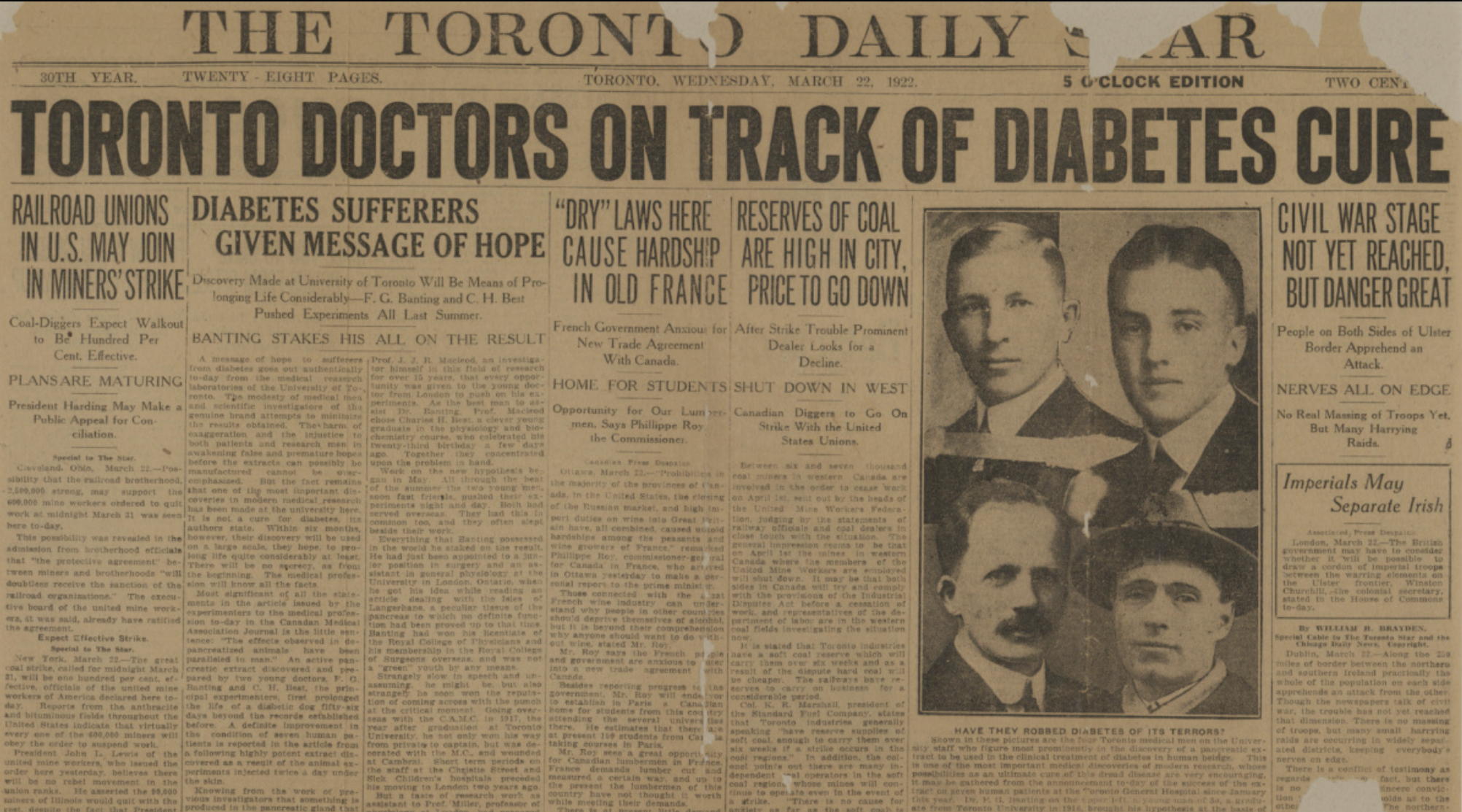

The news spread like wildfire. By year’s end, insulin was distributed across North America and Europe. The discovery was hailed as a resurrection from death, and Banting—introspective, intense, and morally driven—was cast as a national hero.

But behind the glory, tensions were growing. Who truly deserved the credit? Banting and Best for the dog work? Macleod for the lab and scientific oversight? Collip for the crucial purification? The team had succeeded, but their unity did not survive the discovery.

Insulin had been discovered. But the Insulin Wars were just beginning.

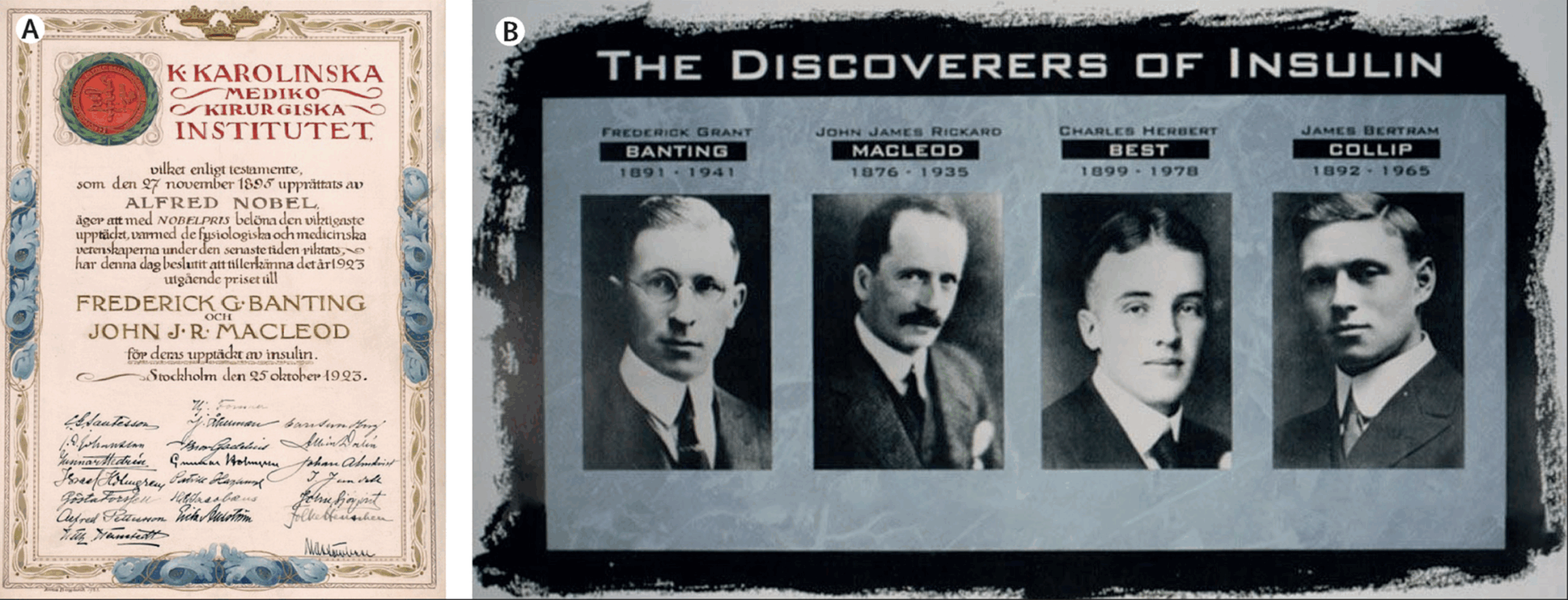

Four Men, One Miracle

Behind the miracle of insulin were four men—each indispensable, flawed, and shaped by the human forces of ego, urgency, and ambition. Together, they changed medical history, but they would not stay together for long.

Frederick Banting: The Reluctant Hero

He was thirty, restless, and nearly broke. Frederick Banting had returned from World War I with physical scars and a gnawing sense of purposelessness. Working part-time as a surgeon and lecturer, he stumbled across a line in a journal article late one October night in 1920. It sparked a crude idea—tie off the pancreatic ducts, wait for the exocrine tissue to degenerate, and extract what remained.

It was barely a hypothesis. But Banting’s conviction was all-consuming. He fed the dogs himself and slept on a cot beside them. He fought with his colleagues and ignored protocol. He wasn’t chasing academic prestige—he was chasing time and the memory of children he’d watched waste away.

When insulin worked, it wasn’t just a triumph. For Banting, it was redemption.

Charles Best: The Steady Hand

Just twenty-two and a second-year medical student, Charles Best joined Banting by coin toss. Where Banting was impulsive, Best was measured, charting data, running tests, cleaning glassware, tending to the dogs with quiet care.

He was the stabilizer. While Banting stormed and agonized, Best recorded the results, adjusted doses, and stayed up late, logging everything they learned. He never asked for credit. But when the Nobel Prize excluded him, even Banting was outraged.

History would eventually remember Best as more than an assistant. But in the moment, he was the essential man left in the shadows.

James Collip: The Quiet Chemist

James Collip joined the team later—but insulin might never have reached a human arm without him.

A skilled biochemist, Collip was brought in when the early extracts caused fevers and abscesses. In just weeks, working alone, he found a way to purify the hormone, remove toxins, stabilize the formulation, and make it suitable for injection.

It was Collip’s version that saved Leonard Thompson in January 1922. But collaboration turned to conflict. Tensions with Banting escalated to the point where Collip reportedly kept his methods secret from the rest of the team.

When honors were handed out, his name was left behind. Yet without his quiet precision, insulin might have remained a crude experiment that worked only in dogs.

J.J.R. Macleod: The Architect in the Background

He never injected a dog or distilled an extract. But he gave the idea its first oxygen.

A Scottish physiologist and department chair, Macleod was skeptical of Banting’s proposal—but curious enough to grant him ten dogs, a student assistant, and a dusty summer lab. When promising results emerged, Macleod stepped in—refining the methods, interpreting data, arranging scientific presentations, and later bringing in Collip to help.

To Banting, Macleod’s growing role felt like intrusion. However, Macleod provided legitimacy and structure to the outside world. He ensured insulin wasn’t just a miracle in a backroom, but a medical discovery the world could trust.

He would share the Nobel Prize with Banting—a decision that ignited resentment and fractured the team permanently.

Act II: Conflict and Division

The team behind insulin fractured almost as quickly as it formed. Fame turned collaborators into rivals. Recognition stirred resentment.

The Nobel That Split the Lab

The official announcement came in October 1923: the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine would be awarded jointly to Frederick Banting and J.J.R. Macleod for the discovery of insulin.

To the world, it was a moment of triumph. To Banting, it was betrayal.

He had fought for every inch of the insulin discovery—through sleepless nights, animal surgeries, and failed experiments. In his eyes, Macleod had done little but supervise. Worse, Charles Best—the young man at his side every hour of that transformative summer—had been left out entirely.

Banting was so incensed that he publicly announced he would share half of his Nobel prize money with Best. Quietly and with far less fanfare, Macleod did the same, giving half his award to James Collip.

But the damage was done. What had once been a team was now a set of factions. Best and Banting grew closer. Macleod drifted away. Collip returned to biochemistry, disillusioned by the infighting.

The Nobel had crowned a discovery. But it had also drawn a line.

Fractures That Never Healed

The Nobel didn’t just divide a team—it shaped their futures.

Banting, catapulted to instant fame, found the spotlight uncomfortable and the scientific community untrustworthy. He struggled with depression and resentment, convinced that Macleod had tried to steal credit and that Best had not always defended him. Though he continued his research and co-directed the Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, he never again made a discovery of similar magnitude. He died in a plane crash in 1941 at the age of 49—a national hero, but a restless one.

Best rose steadily through academic ranks. Though overlooked by the Nobel Committee, he gained recognition over time, becoming a professor, department head, and a respected figure in Canadian medicine. In later years, he sometimes reshaped the story of insulin in ways that favored his own role, which drew criticism from some historians. Still, he outlived them all and remained a symbol of dedication and perseverance.

Collip returned to his work in biochemistry. He rarely spoke publicly about the insulin episode. In the following decades, he helped isolate other hormones and contributed to significant advances in endocrinology. Of all the men involved, he was the least concerned with fame.

Stung by Banting’s hostility and public tension, Macleod left Toronto and returned to Scotland. He became dean of medicine at the University of Aberdeen but never quite escaped the shadow of the insulin feud. His name faded in popular retellings, though modern historians have worked to restore his reputation as the intellectual scaffolding behind the breakthrough.

Insulin had saved lives—but for its discoverers, it had left a trail of fractured friendships and uneasy legacies.

Reconstructing the Story: Michael Bliss and the Insulin Legacy

For decades, the story of insulin was told in fragments—heroic, selective, and often sanitized. Banting was remembered as the brilliant underdog, Macleod as the undeserving supervisor, and Best as the forgotten sidekick. James Collip barely registered at all.

That changed in 1982 with the publication of Michael Bliss’s The Discovery of Insulin. Drawing on lab notebooks, personal letters, and institutional archives, Bliss reconstructed the tangled narrative, revealing the interpersonal fractures, overlooked contributions, and bureaucratic scaffolding that made the discovery possible.

Bliss didn’t diminish Banting’s grit or vision, but he contextualized it. He highlighted how Collip’s biochemistry transformed insulin from an idea into a viable therapy. He rehabilitated Macleod’s image as the architect of order and legitimacy. And he challenged Best’s later efforts to reshape the story in his own favor.

More than four decades later, Bliss’s work remains the definitive history—assigned in medical schools and cited in discussions of ethics, authorship, and scientific teamwork. It turned insulin from a triumphalist myth into a messy and magnificent human story.

It didn’t erase the conflict. It clarified it.

Act III: From Patient to Profit

Insulin was meant to be shared. Instead, it became a product—branded, patented, and priced. As the miracle spread, so too did inequity.

The Dollar That Changed the World

When Frederick Banting, Charles Best, and their collaborators sold the patent for insulin to the University of Toronto for one dollar, the gesture was meant to speak for itself: no one should profit from a life-saving hormone.

They believed the discovery belonged to humanity. “Insulin does not belong to me,” Banting said. “It belongs to the world.”

But the world had other ideas.

To scale production, the university licensed insulin manufacturing to Eli Lilly & Co., a pharmaceutical firm with industrial capacity and commercial muscle. Within a year, insulin was being mass-produced in the United States, and not long after, companies in Europe—Nordisk in Denmark and Hoechst in Germany—joined the effort.

For a time, the balance held. Production expanded. Competition kept prices in check. The molecule was shared—even if imperfectly.

From Hormone to Commodity

Then came the biotechnology revolution.

In the 1980s, animal-derived insulin was replaced by recombinant human insulin, which was made by inserting the human insulin gene into bacteria or yeast. This genuine innovation reduced impurities and improved consistency. But with this breakthrough came new patents, and with new patents came renewed profit.

Soon after, a second transformation began: the rise of insulin analogs—synthetic variants engineered for longer or faster action. Each adjustment brought new exclusivity periods. Each reformulation, however incremental, reset the patent clock.

Delivery devices evolved too—pens replaced syringes, with improved convenience but higher prices. The science had advanced, yes—but the business model had evolved faster.

This strategy, known as evergreening, became the backbone of insulin economics. As the original patent expired, pharmaceutical companies introduced minor tweaks in formulation or device to secure new intellectual property protections—extending their monopolies without significantly changing the drug itself.

By the early 2000s, three companies—Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi—had consolidated control of the global insulin market. Today, they manufacture over 90% of the world’s supply.

A Gift Wrapped in Barbed Wire

What began as an act of altruism was slowly encased in legal armor. Banting had imagined insulin as a public good. A century later, it had become a private asset—defended by armies of patent lawyers and priced for maximum yield.

The science had stabilized. The systems had not.

Critics call it a betrayal of the original spirit. Minor chemical adjustments now justify multi-hundred-dollar price tags. Generic manufacturers face steep barriers to entry, not from biology, but bureaucracy. And patients—millions of them—find themselves caught between necessity and affordability.

It wasn’t the molecule that failed. It was the model.

When the Same Drug Costs Less

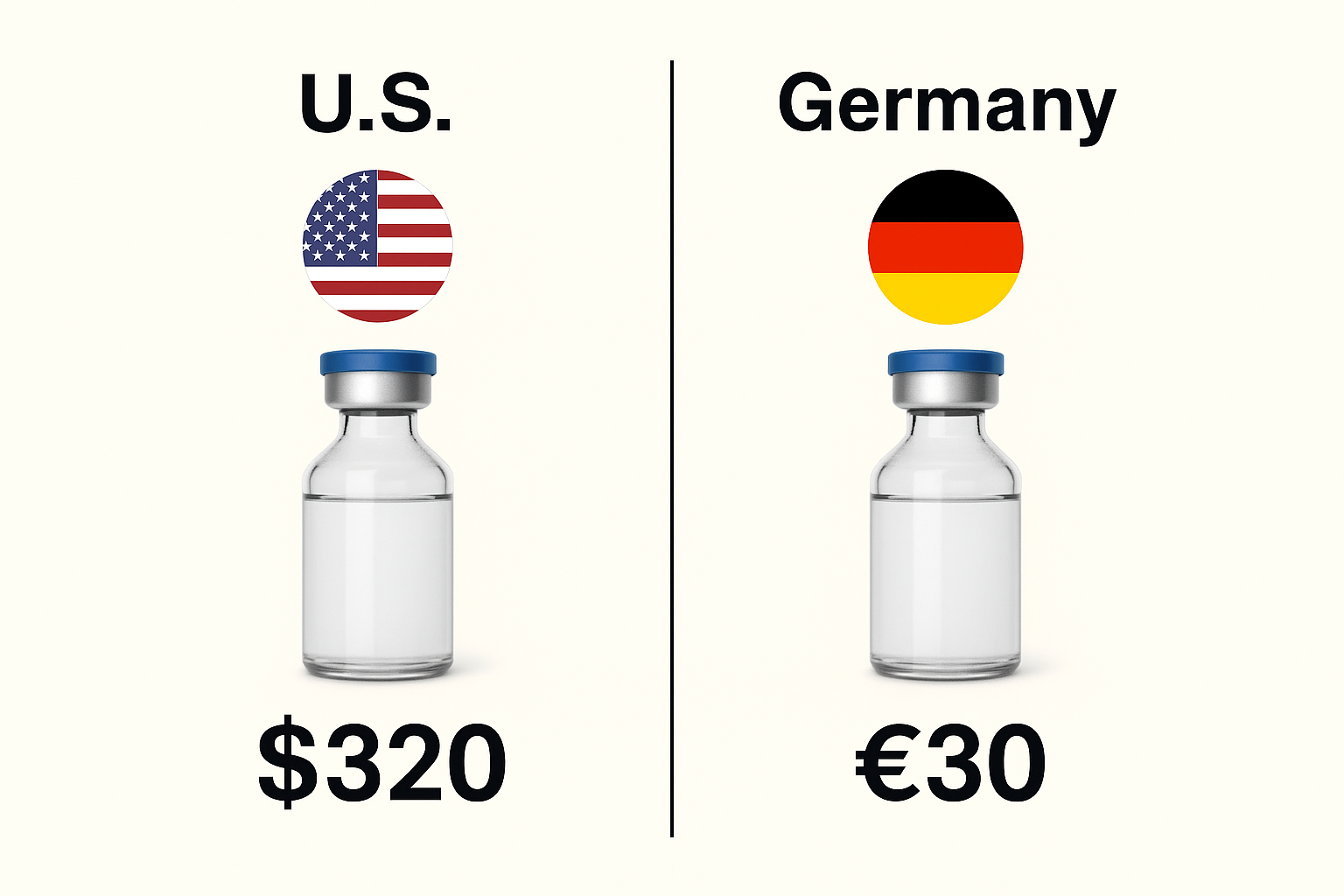

The pricing crisis is not universal. In most European countries, insulin costs a fraction of what it does in the United States. A vial that might cost $300 or more in the U.S. can sell for $30 or less in Germany, France, or the Netherlands. The difference isn’t due to production costs—it’s about policy.

European governments negotiate directly with pharmaceutical companies, using national health systems or price-setting agencies to keep costs in check. Insulin, an essential medicine, is often fully covered or heavily subsidized. There are no pharmacy benefit managers, no hidden rebates, and far less corporate lobbying.

In the U.S., by contrast, Medicare was long prohibited from negotiating drug prices. Insulin prices are shaped by a fragmented system of private insurers, Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), wholesalers, and manufacturers—all adding layers of markup. Even with reforms like the $35 Medicare cap, uninsured and underinsured Americans still face enormous costs.

Same drug. Same manufacturers. Different rules. Different outcomes.

Policy Collisions

Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden tried to lower insulin prices, but they were met with fierce resistance.

Trump’s administration proposed tying Medicare prices to those paid by other wealthy nations, a move that would have slashed insulin costs. Pharmaceutical lobbyists immediately attacked the plan, which was quietly shelved.

Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act finally capped insulin costs at $35 a month for Medicare beneficiaries, but millions of Americans—especially the uninsured or underinsured—remain exposed to full retail prices.

In the background, insulin makers continue to post record profits. Their CEOs testify before Congress. They publicly apologize and promise voluntary price reductions—then raise prices elsewhere, or introduce new analogs just different enough to reset the patent clock.

It’s a game. And patients are losing.

The Price of a Miracle

Alec Smith was twenty-six when he aged out of his mother’s health plan. His insulin now cost him over $1,300 a month. He tried to ration it. He died just days later.

Alec wasn’t reckless. He was working full time as a restaurant manager in Minnesota, living independently, and trying to build a life. But without employer-sponsored insurance and with no affordable individual coverage, he was left to choose between rent and survival. His family later found half-used vials and syringes in his apartment. He had been stretching doses—carefully, quietly, and fatally.

His mother, Nicole Smith-Holt, would become one of the most vocal advocates for insulin affordability in the United States. She has testified before lawmakers, marched with patient groups, and turned her grief into a movement. Alec’s story has since become a symbol of what happens when life-saving medicine is priced beyond reach.

His death wasn’t a medical failure. It was a financial one. And it wasn’t rare.

“Big Pharma should not be allowed to put a price tag on our lives. We need for you to create and pass laws that protect us all from a certain death of corporate greed.”

— Nicole Smith-Holt

The Human Cost

According to the World Health Organization, over half of the people worldwide who need insulin don’t have reliable access to it. And for those who do, the cost can be crushing.

A vial of insulin costs about $3 to manufacture. In some low-income settings, it’s sold for $25—or not at all. Local wages often make that cost insurmountable.

Doctors Without Borders describes this as a “humanitarian failure.” Parents are forced to make impossible choices: buy insulin or buy food. Treat one child or let another go without.

A physician in Uganda recounted seeing a teenage girl die in his clinic after rationing her insulin for weeks. “She didn’t need new science,” he said. “She needed access.”

Even when insulin is donated through aid programs, availability can shift overnight—subject to changing political winds, donor fatigue, or fragile logistics.

Insulin isn’t just a molecule. In much of the world, it’s a measure of health system strength—and a reflection of global inequality.

The Global Divide

Insulin may be essential—but across much of the world, it remains elusive. Access is patchy and precarious in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America. Clinics run out. Refrigerators fail. Families travel for hours only to find nothing.

This isn’t due to lack of science. It’s due to structure.

Most low-income countries cannot produce insulin locally. Instead, they depend on a handful of multinational firms—chiefly Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi—for imports. With just three companies controlling over 90% of the market, pricing and supply are dictated not by need, but by leverage.

Infrastructure only deepens the divide. Cold storage is scarce, and bureaucracy stalls deliveries. Even when donated, insulin can sit idle, stranded by customs paperwork or political gridlock.

A study in The Lancet described it bluntly: “Insulin access in low-income settings is dictated by market power, not medical need.”

In Sudan, shipments arrive spoiled. In India, families reuse boiled syringes. In Venezuela, insulin is traded through underground WhatsApp groups. This isn’t an exception—it’s the pattern.

Even nonprofit efforts face resistance. In 2022, a biosimilar initiative in Kenya aimed to launch low-cost insulin but collapsed due to licensing delays and raw material costs. The market was technically open, but functionally, it was rigged.

The System Isn’t Broken – It’s Built This Way

In Detroit, parents plead for insulin samples on Facebook. In Bangalore, children die waiting for shipments delayed by floods. In refugee camps, aid groups ration doses to the youngest patients.

None of this is necessary.

Insulin is not rare, does not require exotic ingredients, and is not a miracle drug that must be rationed like a rare organ. It is reproducible, scalable, and essential.

What stands in the way is not chemistry, but commerce.

The insulin crisis is not the result of scientific limitations. It is the consequence of a system that places patents above patients, markets above morality. What began as a gift to humanity has become a gate—guarded by bureaucracy, inflated by policy failure, and locked behind the cold arithmetic of quarterly earnings.

And still, the need remains constant. Every minute of every day, someone’s life depends on this molecule. The tragedy is not in its scarcity—but in its mismanagement.

Epilogue: A Molecule Still on Trial

A hundred years ago, a restless surgeon in Toronto helped pull a miracle from obscurity. Insulin didn’t cure diabetes, but it changed the ending. It gave children back their futures, and it gave parents back their hope.

But what began as a gift was slowly absorbed into a system that forgot why it was made.

Today, insulin remains a triumph of science—and a failure of systems. It is rationed in rich countries and missing in poor ones. It is shielded by patents, inflated by policy, and traded as a commodity.

The molecule never changed. What did was everything around it.

And yet, the story isn’t over. Around the world, advocates are pushing back. Countries are rewriting procurement laws. Biosimilars are breaking through patent walls. Families, doctors, and activists are refusing to accept a system that puts price above survival.

“Insulin does not belong to me. It belongs to the world,” Banting said.

That promise has not been kept. But it still can be.

Because the real legacy of insulin will not be measured only in vials or patents. It will be measured in whether we choose to treat medicine as a right or continue to sell it as a privilege.

📚 Sources & Further Reading

- Bliss, Michael. The Discovery of Insulin. University of Chicago Press; 1982 (Reissued 2007).

- Banting FG, Best CH, Collip JB, Campbell WR, Fletcher AA. Pancreatic extracts in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Can Med Assoc J. 1922;12(3):141–6.

- World Health Organization. Improving access to insulin. WHO, 2021. View report

- Beran D, Ewen M, Laing R. Insulin access and affordability: A call to action. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):738–40.

- Gagnon M-A, Lexchin J. The cost of pushing pills: A new estimate of pharmaceutical promotion expenditures in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e1.

- Liu Y, Zhang Y, Vortherms SA, et al. Access to insulin products in the U.S. JAMA. 2022;328(1):44–53.

- Greene JA, Riggs KR. Why is there no generic insulin? N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1171–5.

- Luo J, Kesselheim AS, Greene J, Lipska KJ. Strategies to improve the affordability of insulin in the USA. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(6):405–8.

- McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Dunlay SM, et al. Access and cost barriers to insulin. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):112–4.

- Thomas K. The Human Cost of Insulin in America. The New York Times, January 2019. Read article

- Beaton A, et al. Insulin pricing and distribution in low- and middle-income countries. Health Affairs Blog. 2020. Read post

- Belluz J. The absurdity of modern insulin prices in one chart. Vox. October 2018. View chart

- T1International. #Insulin4All Campaign. Visit the campaign site

- Hirsch IB. Insulin in America: A Right or a Privilege? Diabetes Spectrum. 2020;33(1):1–2.

- Feldman WB, Greene JA. A Century of Insulin: A Story of Innovation and Ambition. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(11):1001–3.

Portions of this article were developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model by OpenAI, to help refine structure, language, and clarity while preserving the author’s voice and scientific integrity

$3 to manufacture and sold at $320. Maybe an altruistic entrepreneur will figure out how to get generic insulin to the public at a far lower price.

Entrepreneur Mark Cuban started a company to enable people to bypass the Pharmaceutical Benefit Managers. It is called Cost Plus Drugs. People can buy drugs at the cost the company buys it for + 15% + $5 pharmacy fee + $5 shipping. He is pursuing legal action against pharmacy benefit managers who are playing hardball with drug manufacturers and hospitals and clinics, so that they can illegally keep their monopoly. There is no need for pharmacy benefit managers in a free market system. I wish him success!