Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, Medicating Appetite: The GLP-1 Dilemma, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

At first, they were diabetes drugs.

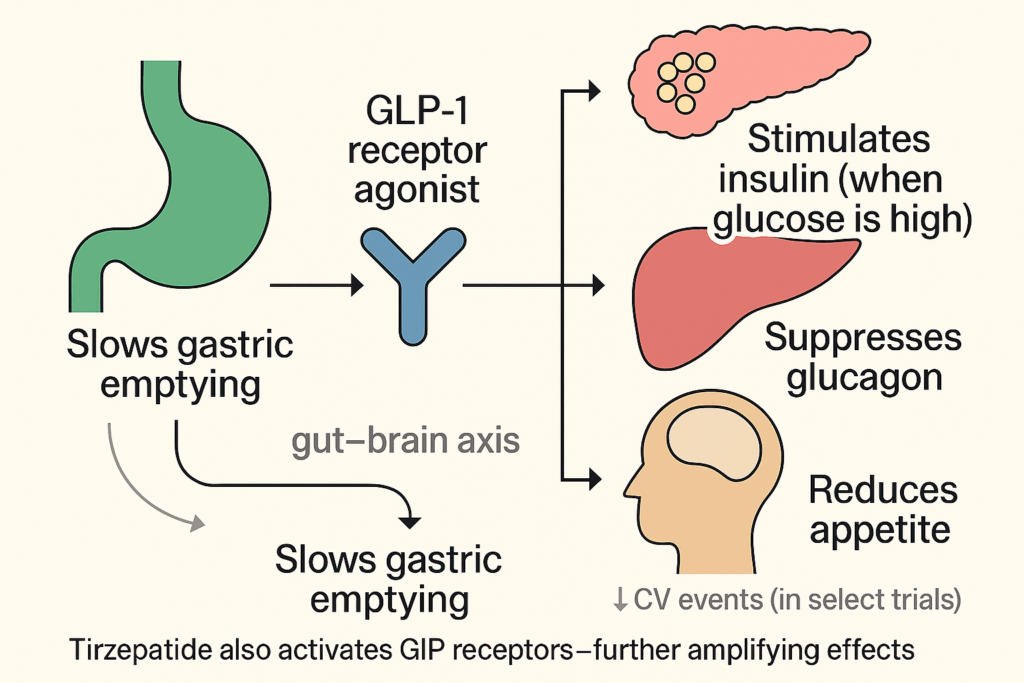

GLP-1 receptor agonists—liraglutide, semaglutide, and later tirzepatide—were developed to help patients with type 2 diabetes regulate blood sugar. They mimicked a gut hormone, GLP-1, that modulates insulin, glucagon, and gastric emptying. They also acted on the brain.

Appetite went down.

Weight came off.

And people noticed.

Ozempic (semaglutide) became a household name—mocked on late-night TV, trending on TikTok, hailed by investors as the next statin, and requested by patients everywhere.

By 2021, semaglutide was approved again—this time as Wegovy, for chronic weight management. It wasn’t just a rebranding. It was a signal.

A drug that silences hunger had gone viral.

Soon came tirzepatide—Mounjaro, then Zepbound. Even greater weight loss. More demand. A full-blown boom.

GLP-1s had moved beyond endocrinology. Into lifestyle clinics, wellness spas, gym locker rooms. Into a marketplace that sells control.

And for many, they delivered:

- 10%, 15%, or even 20% body weight lost

- Lower glucose, blood pressure, and inflammation

- Fewer heart attacks, as seen in the SELECT trial

It felt like medicine had cracked the metabolic code.

But with speed comes risk.

We are now prescribing these drugs to millions of people—some with diabetes, others without. Some with obesity, others merely uncomfortable with their bodies. Some for medical necessity, others for self-improvement.

What we don’t yet know is what this means long-term.

- What happens when hunger is pharmacologically muted, year after year?

- What is the cost of using a powerful metabolic signal as a tool of aesthetic control?

- And are we ready for a future where appetite itself is considered a chronic condition?

This is not a rejection of GLP-1s. It’s a call for clarity.

This article will explore:

- What these drugs do—and what they don’t

- Where the science is solid—and where it isn’t

- How cultural euphoria can outpace clinical understanding

- And what it really means to lose weight when hunger is no longer part of the story

Because in the end, this isn’t just about one drug or one disease. It’s about the kind of healthcare system we’re building—one where long-term metabolic risk is managed through lifelong pharmacology.

That may be progress.

But it may also be a signal that something deeper is being left untreated.

“The pursuit of health is never entirely innocent.”

— Ivan Illich

A Timeline of Trials

It began quietly in 2005 with exenatide—the first GLP-1 receptor agonist. Initially, it was a modest tool in the diabetes arsenal: enhanced insulin release, suppressed glucagon, slowed gastric emptying. Useful, yes. Game-changing? Not yet.

Then came the surprise: patients began to lose weight. More than expected. More than predicted. That “side effect” would soon become the headline.

2010–2016: From Glucose Control to Cardiac Benefit

Liraglutide (Victoza) arrived in 2010. At first, another glucose-lowering option. But in 2016, the LEADER trial revealed a new dimension: fewer cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Suddenly, GLP-1s were contenders in heart disease prevention.

2021: STEP Changes the Game

The STEP trials brought semaglutide into the spotlight. In STEP 1, patients with obesity (without diabetes) lost nearly 15% of body weight on weekly semaglutide. STEP 2, 3, and 4 confirmed and extended the findings. Patients didn’t just weigh less—they functioned better.

2022–2023: Tirzepatide and the SURMOUNT Trials

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) raised the bar. In SURMOUNT-1, non-diabetic patients lost up to 21% of body weight. For some metrics, it rivaled bariatric surgery.

2023: SELECT Changes the Landscape

The SELECT trial enrolled over 17,000 patients with obesity or overweight—but no diabetes—all with cardiovascular disease. Semaglutide reduced heart attacks, strokes, and cardiovascular death by 20%. This was no longer a glucose drug. It was preventive cardiology.

The Bottom Line

In under two decades, GLP-1 agonists moved from niche diabetes drugs to pillars of cardiometabolic care—lowering glucose, reducing weight, and, as SELECT showed, preventing heart attacks.

That isn’t marketing. It’s robust evidence. But the story has moved quickly. Too quickly, perhaps.

The Price: What If the Bill Comes Later?

Every medical breakthrough has a bill. The GLP-1 story is still unfolding, but the early receipts are in. The trials were well-designed, the results compelling. But they had limitations: short timelines, selective populations, and controlled conditions.

Now, the real-world use is broader, messier—and more revealing. Millions of people—many without diabetes or severe obesity—are now on GLP-1s. Not all are monitored. Not all are informed.

The Negatives: What the Trials Showed

Across programs like STEP, SURMOUNT, and SELECT, side effects were largely gastrointestinal: Nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea.

Early satiety, bloating, and abdominal discomfort. These were dose-dependent and typically transient. Still, 5–12% of participants discontinued the drug, and the rate was higher at maximum doses.

Other findings included:

- Gallbladder issues (especially with rapid weight loss)

- Pancreatitis (rare, with unclear causality)

- Thyroid C-cell hyperplasia (in animals, not seen in humans)

- Lean mass loss—up to 40% of weight lost may be muscle in older adults

None of these derailed regulatory approvals. But they added shadows to the spotlight.

What’s Emerging in Practice Outside of Trials

GLP-1s live in the wild—prescribed broadly, dosed variably, and sometimes obtained without medical oversight.

Gastroparesis. Emergency departments have noted rising cases of delayed gastric emptying. Severe nausea. Vomiting that persists. Feeding tubes, even hospitalizations.

GLP-1s should slow digestion. That’s part of the therapeutic mechanism. But when does “slowed” become “stopped”?

Emotional Dulling. A quieter trend: people saying they feel… flat. Not just less hungry. Less motivated. Less emotionally responsive. Are we silencing hunger alone—or something deeper in the reward system?

The Off-Ramp Problem. Almost universally, stopping the drug leads to weight regain. That’s not a moral failure. It’s physiology. Appetite rebounds. Ghrelin rises. Fat mass returns. Which means the drug may need to be continued indefinitely.

So what happens after 10 years? Does the efficacy hold? Does tolerance develop? Do long-term side effects accumulate? We don’t know.

The trials gave us a start. But the rest of the road is unpaved. And while we shouldn’t reject a therapy just because it’s potent, we also shouldn’t race ahead without asking: potent enough for what—and for how long?

The Growing Conversation

At first, the headlines were breathless. Miracle drug. Skinny shot. A revolution in weight loss. But as these injections have spread, the tone has shifted. Excitement hasn’t vanished—but it now shares space with unease.

The key question is no longer just does it work? It’s what does it mean?

As The New Yorker has observed, the rise of GLP-1s marks a shift not only in medicine but in culture—as appetite-modulating drugs move from treating diabetes toward shaping body ideals, identity, and social aspiration.

In The Atlantic, Sarah Zhang called them “powerful modulators of appetite,” acting not only through the gut but on the brain itself. This, she argued, reframes hunger from a signal of survival into something medicine can mute at will—forcing us to ask what it means to pharmacologically control desire.

And then there are the voices of patients themselves. Beyond nausea and weight loss, many describe emotional blunting—less joy, less drive, even altered sexuality. A 2024 analysis of online communities found recurring reports of diminished pleasure and libido. A 2025 Kinsey Institute survey revealed that more than half of GLP-1 users said the drugs had changed their sex and dating lives—sometimes for the worse.

These aren’t just side effects. They are reflections of meaning. Are we treating a medical problem, or rewriting the experience of appetite itself? What happens to our sense of self when hunger can be turned off like a switch?

The Boom: From Treatment to Trend

If The Growing Conversation is about meaning, The Boom is about momentum. And the numbers are staggering.

In the U.S., GLP-1 prescriptions more than doubled in just 18 months, topping nine million by early 2024. Demand outstripped supply. Pharmacies ran dry. Compounding labs and gray-market sellers stepped in. Oversight evaporated. Appetite was now a commodity, and the market couldn’t move fast enough.

The approved lanes—type 2 diabetes and obesity—blurred almost instantly. Executives, athletes, and casual dieters joined in. Some clinics skipped labs altogether; telehealth startups promised effortless access; influencers became unpaid brand ambassadors, amplifying demand faster than regulators could respond.

Meanwhile, Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly surged into the ranks of the world’s most valuable companies, pipelines swelling with oral formulations, dual and triple agonists, and weight-loss hybrids that fold in amylin and other pathways. Rivals are flooding in, with dozens of compounds already in mid- to late-stage trials.

Over the next five years, the marketplace will only grow more crowded: cheaper generics, oral pills replacing injections, and an escalating marketing war as companies expand indications from diabetes and obesity into sleep apnea, fatty liver disease, even addiction.

But this boom has a cost. The drugs run $800 to $1,500 a month, with patchy insurance coverage. Those with means can buy marginal benefit. Those with medical need often struggle for access. Others turn to risky knockoffs. Equity is eroding even as markets expand.

What began as a breakthrough in metabolic care has become an arms race of pharmacology and finance. The question is not whether this market will keep growing—it will. The question is who it will serve, and whether the ultimate prize is treatment, profit, or ownership of hunger itself.

Silencing Hunger

The world didn’t just adopt GLP-1s. It embraced them.

What began as a treatment for diabetes became something bigger—faster than anyone expected. These drugs leapt from clinics to culture, from endocrinology to aspiration. Hunger was no longer just managed. It was optional.

But that raises a deeper question: What, exactly, are we changing?

Hunger is not just a nuisance. It is one of the body’s oldest regulators. It shifts with sleep, memory, glucose, inflammation—even emotion and love. It reminds us we are alive. That we want. That we need.

Now, for millions, that signal is being switched off.

For patients with severe obesity and metabolic disease, this is a gift—life-extending, even lifesaving. But once use moves from need to want, from clinic to culture, the ground shifts.

What happens to our relationship with food when hunger is no longer a guide?

What messages do children absorb when appetite suppression is normalized?

How do we define body image in an era when biology can be modulated on demand?

These are not questions of side effects. They are questions of meaning.

And Then What?

The trials lasted two, maybe three years. The weight loss lingered a while. The headlines? Gone in six months.

But what happens after that?

No one knows what ten or twenty years on GLP-1s will look like—in real bodies, in everyday lives.

What we don’t yet know matters:

- Muscle and bone — will long-term lean mass loss leave people weaker, more fragile?

- Cognition and mood — does chronic appetite suppression alter dopamine tone, motivation, or emotional range?

- Reproductive health — what happens to fertility, pregnancy, or hormone balance after decades of use?

- The gut — how does a digestive system slowed for years adapt, or fail to adapt?

Imagine someone who starts semaglutide at 32 and stays on it until 50.

Will the drug still work? Will hunger return—stronger, or stranger? Will subtle scars appear that today’s short trials are unable to reveal?

Long-term safety isn’t a headline. It’s a question of time. And time, so far, hasn’t answered.

Epilogue – The Hunger That Remains

No drug is neutral. Especially not one that tamps down something as ancient as hunger.

GLP-1 agonists have earned their place in modern medicine. For patients with severe obesity and metabolic disease, they save lives. That is real, and it should not be dismissed.

But millions are now taking these drugs far beyond those boundaries. We are running a global experiment at scale, with no long-term map. And experiments have consequences.

So the question is not only what happens if something goes wrong? It is who answers for it?

If decades from now we discover hidden costs—fractured bone, blunted emotion, reproductive harm, cognitive change—who carries the blame?

- The patient who asked for help?

- The doctor who prescribed?

- The regulators who approved?

- Or the companies that turned hunger into a gold mine?

Progress is real. But responsibility is real, too.

Because when medicine expands this quickly, it is easy for celebration to drown out caution. Easy for accountability to dissolve in the boom. Easy to forget that the appetite we are silencing is not only biological—it is human.

So we should pause. Not to reject progress, but to claim ownership of its risks.

Otherwise, we may wake up years from now with a thinner population, a richer industry, and a silent hunger that has left its own scars.

“Medical science has made such tremendous progress that there is hardly a healthy human left.”

— Aldous Huxley

✅ GLP-1 Agonists at a Glance

First-Generation (Short-Acting)

• Exenatide – Byetta

• Lixisenatide – Adlyxin / Lyxumia

Second-Generation (Long-Acting)

• Exenatide ER – Bydureon (weekly, now discontinued in some markets)

• Liraglutide – Victoza (diabetes), Saxenda (obesity)

• Dulaglutide – Trulicity

• Semaglutide – Ozempic (diabetes), Wegovy (obesity), Rybelsus (oral)

Dual Agonist (GIP + GLP-1)

• Tirzepatide – Mounjaro (diabetes), Zepbound (obesity)

Triple or Combination Agonists (In Development)

• Retatrutide – Triple agonist (GLP-1 + GIP + glucagon)

• CagriSema – Combination of cagrilintide + semaglutide (GLP-1 + amylin analog)

• Orforglipron – Oral, non-peptide GLP-1 receptor agonist (Eli Lilly)

• Danuglipron – Oral small-molecule GLP-1 agonist (Pfizer)

• Efinopegdutide – GLP-1/glucagon dual agonist (Merck/Biocon)

• AMG133 – GLP-1 + GIP receptor modulator (Amgen)

I think you give too much credit to Peter Attia, who has been wrong about many things over the years.

Thanks for your comment. Just to clarify — Peter Attia isn’t actually mentioned in the article. My aim was to focus on the broader science and cultural implications of GLP-1 drugs, rather than any individual’s views.

I appreciate you taking the time to read and share your perspective.

Great review with important unanswered questions raised, applicable to new drugs in general that have been studied for short time periods.

Thanks Bob— you’re right. It’s the same story with many new drugs: we get short-term data, but the long-term picture takes years to unfold.

I hope this doesn’t happen: Marketing machines target physicians and citizens so it becomes normalized. Huge portion of the population start taking it, including many children. See it get on “approved list” of insurance companies, raising insurance rates and costing the government a fortune. Sounds like people will be on it for life, so they may need to add new drugs for side effects: bone strengthening drugs, dopamine for cognition and mood, reproductive drugs, and gut drugs. Someone who starts taking Semaglutide at 32 may not need to at 50, because all these drugs may destroy their liver and put them in an early grave. I hope physicians encourage, and citizens try, the more difficult route of diet and exercise which has the side effects of better mood and more energy.

One bright spot is city planning. New designs for housing tracts encourage people to get outside, walk and socialize. These have trails, and common areas with benches, tables and landscaping. In my city, they are adding new bike paths and converted part of the main shopping street to pedestrian only. Most of the new approved housing is downtown where many businesses are located. New condominiums and apartments. Instead of a driving commute, your morning commute will be walking a few blocks. No need to drive to entertainment, or a restaurant, it’s all right there.

Thank you for sharing these concerns Andy. You highlight a real tension: the pull of quick pharmacological fixes versus the harder, but often more sustainable, path of lifestyle change. If GLP-1s become normalized too quickly, we risk creating new problems while only partially addressing old ones. I also appreciate your point about city planning — environments that make activity and social connection easier may prove just as powerful for long-term health as any drug.

As you well know, the GLP-1 drugs are being used prophylactically (way off label) for a wide variety of possible ailments. Your readers can type “GLP-1 for everything” in a google search.

For the most part, it is not understood why a small dose of a GLP-1 drug would help prevent (or even treat) these ailments but there is a lot of evidence that it does.

But one writer commented that rather than everyone start shooting up a GLP-1 drug, it would be best if we study why/how GLP-1 drugs work in these “off label” ways which would add to our understanding of physiology and perhaps aid in the development of more specifically focused drugs.

Thank again for all you do.

Philip Thackray

Thank you, Philip — I think you raise a very important point.

GLP-1 drugs are indeed being explored for a long list of conditions far beyond diabetes and obesity. The enthusiasm is understandable, but as you suggest, it’s one thing to observe benefit, and another to understand why. Until we grasp the underlying mechanisms, we risk running far ahead of the science.

I think that studying these off-label signals could teach us much about physiology and metabolism — perhaps even open the door to safer, more targeted therapies down the road. That kind of work is less glamorous than prescribing what “seems” to help, but ultimately it’s what medicine needs.

Thanks again for adding this perspective to the discussion.

Thank you for your insightful articles. I always enjoy soaking up new information.