Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

There’s a story I want to share. It’s true—but more than that, it’s revealing. It’s about what really shapes the food we eat—not just biology or taste, but something deeper: belief. Sometimes even religious belief, dressed up as personal preference or disguised as science.

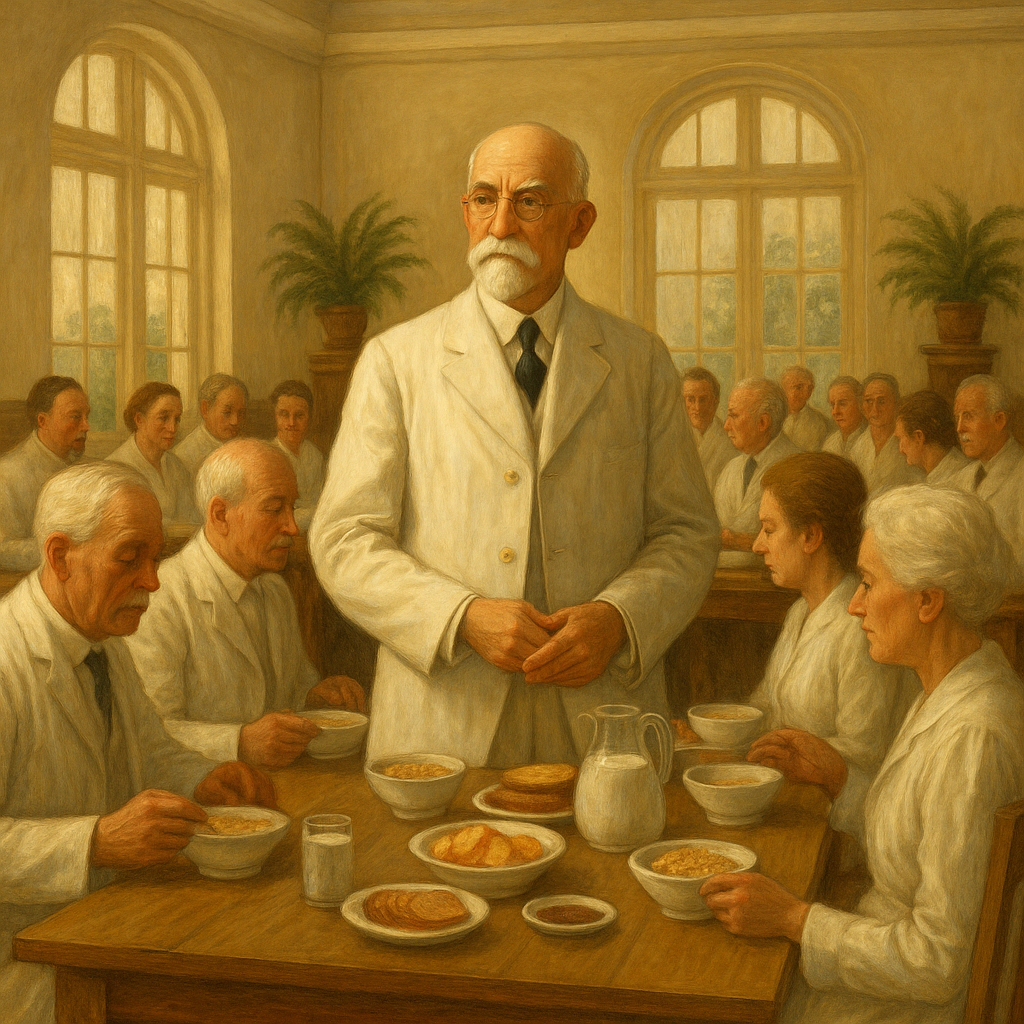

It begins with a doctor, a bowl of cereal, and a crusade against sin.

Why do we eat the way we do? Is it simply biology—our brain’s craving for sugar and fat—or is it learned behavior, shaped by family dinners and cultural rituals? Is it advertising, telling us what’s trendy? Or science, telling us what’s best? Probably all of the above.

And yet, something more elusive also seems to guide us.

Over time, I’ve come to believe that the way we eat is not just a reflection of biology or habit—but a mirror of our values, our identities, and even our belief systems. Some of our food choices are rational. Many are emotional. And a surprising number are, whether we realize it or not, spiritual.

We may no longer bow our heads before meals, or speak aloud to the heavens. But we still believe in “good” foods and “bad” ones. We use language like “clean eating,” “cheat meals,” “guilt-free snacks.” We don’t just eat. We atone, we aspire, we signal.

This idea came into focus for me while reading about Dr. John Harvey Kellogg and the Battle Creek Sanitarium. Here was a doctor who didn’t just believe in healthy eating—he believed in holy eating. In his world, dietary rules weren’t just guidelines. They were commandments. And cereal wasn’t just a health food—it was a sacrament.

This article tells that story. But it also invites a broader question: when we talk about nutrition today, how much are we talking about evidence—and how much are we unconsciously retelling an old gospel about sin, purity, and salvation?

In the world of diet culture, food becomes more than fuel. It becomes a symbol of who we are—or who we wish to be.

This is a story about that transformation. About how, in one strange corner of American history, dietary rules were lifted from scripture, sin was measured in meat, and cereal was cast as salvation.

The Sanitarium Awakens

It’s 6:30 a.m. at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in 1905. Outside, the Michigan morning is cool and gray, but inside, a rigid calm has taken hold. Patients file silently into the breakfast hall—no idle chatter, no clinking cups. Just the hush of discipline and ritual.

The room smells faintly of wet grain and disinfectant. White-robed men and women sit in rows, backs straight, eyes forward. On the tables: bowls of flaked cereal, stewed prunes, and warm water—served without sugar, salt, or joy. There is no coffee. No bacon. No buttered toast. Flavor is temptation. Stimulation is sin.

This isn’t breakfast. It’s penance.

At the head of this temple of abstinence stands Dr. John Harvey Kellogg—part physician, part preacher, all conviction. To Kellogg, food is medicine. But more than that—it is morality made edible. Every bite is a test of restraint. Every skipped indulgence, a victory over the body’s baser instincts.

He isn’t just feeding patients. He’s purifying them.

Where Religion Met Food

The roots of this strange breakfast lie in a spiritual movement: Seventh-day Adventism.

In the mid-19th century, a growing religious group emerged in America preaching the second coming of Christ, bodily purity, and the spiritual dangers of indulgence. Among their central health messages? Total abstinence from meat, alcohol, tobacco, and even spicy foods.

These weren’t just dietary preferences—they were tools of spiritual discipline. To indulge was to regress. To abstain was to elevate.

Enter Sylvester Graham—a Presbyterian minister who believed that lust, gluttony, and disease all sprang from overstimulated senses. To tame these sinful impulses, he preached a gospel of restraint: coarse bread, bland vegetables, and pure water were his antidotes to moral decay. His now-famous Graham cracker wasn’t meant to delight—it was invented to suppress desire.

From these convictions, Graham built more than just a diet. He crafted a full-blown nutritional theology aimed at preserving the purity of body, mind, and society. At its heart was a strict vegetarian regimen anchored by home-baked bread made from coarsely ground whole wheat flour, free from spices or other “stimulants.” He urged people to sleep on hard beds, avoid warm baths, and live according to a disciplined, natural code. For Graham, this wasn’t merely health advice—it was a moral blueprint for how to live.

Kellogg didn’t just admire Graham—he canonized him. Raised in an Adventist household, Kellogg viewed the human body as a battleground between righteousness and temptation. Meat, in his worldview, was not neutral. It stoked dangerous passions. It was fuel for lust and violence. He once warned that meat-eating parents were corrupting their children’s character through the dinner plate.

Food, then, was a tool for sanctification—or degradation. And Kellogg’s medical mission was less about healing disease than about perfecting the soul through dietary submission.

Kellogg’s Crusade

Armed with a medical degree and a zealot’s conviction, Kellogg transformed his beliefs into method.

He developed a strict, plant-based regimen centered on whole grains, fiber, nuts, and water. He banned alcohol, coffee, tea, and all spices, believing they inflamed the senses and triggered what he called “animal instincts.”

Kellogg’s vision of health was both mechanical and moral. The body, to him, was a system to be regulated and purified. Illness wasn’t just unfortunate—it was often seen as self-inflicted, the consequence of dietary sins and weak moral discipline.

He promoted elaborate therapies to correct these perceived faults. Enemas were prescribed daily to cleanse the colon, believed to be the origin of nearly all disease. Patients were subjected to hydrotherapy, phototherapy, electric stimulation, and “sin-fighting” exercises.

One former patient described the experience as “equal parts spa, boot camp, and religious revival.” Another wrote home: “I came here for my stomach, but they are saving my soul.”

Kellogg also waged war on masturbation, which he called the “solitary vice.” He published extensive warnings about its dangers and advocated circumcision without anesthesia for boys and application of carbolic acid for girls—to deter what he viewed as dangerous self-abuse. It was extreme, invasive, and deeply rooted in a fear of the body’s natural impulses.

In his view, health was not just a state—it was a moral achievement. A mark of the disciplined. A sign of spiritual cleanliness.

And his Sanitarium was not just a hospital. It was a sanctum for the saved.

The Sanitarium as Wellness Temple

The Battle Creek Sanitarium began modestly in 1866 as the Western Health Reform Institute—a small operation run by the Adventist Church. Under Kellogg’s leadership, it transformed into a sprawling institution of more than 400 rooms, complete with surgical suites, research labs, solariums, hydrotherapy baths, and its own farm.

It was part hospital, part luxury spa, and part religious retreat. Guests paid handsomely to be purged, prodded, and spiritually scrubbed. Some came for health, some for status, and some—like Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Amelia Earhart, and President William Howard Taft—for a strange mix of both. Even George Bernard Shaw, though skeptical, was drawn into its orbit.

“You don’t go to Battle Creek merely to be cured,” one patient quipped, “you go to be reborn.”

Kellogg treated the body as a divine machine—one that needed regular maintenance, purification, and above all, discipline. Patients adhered to rigid routines: early rising, cold showers, vegetarian meals, electric light baths, lectures on temperance and purity. It was a blueprint for the modern wellness resort, but with a heavy hand of theological overtones.

And at the center of it all was Kellogg, a man who believed he could engineer moral health as much as physical. “A clean colon is a clean conscience,” he was fond of saying—half in jest, but entirely in earnest.

But not everyone shared his vision.

His brother, Will Keith Kellogg, ran the business side of the Sanitarium. More pragmatic, more entrepreneurial—and crucially, more open to compromise. When John Harvey developed a dry, unsweetened flaked cereal to help patients follow their bland diets, Will saw commercial potential. Against his brother’s wishes, he added sugar. Then he branded it. Then he scaled it.

Thus was born Kellogg’s Corn Flakes—a product that quickly swept the nation and seeded the breakfast cereal empire. To John Harvey, it was heresy: his sacred food, corrupted by capitalism and sweetness.

“What Will has done,” he wrote in a bitter letter, “is take the Lord’s work and dip it in molasses.”

The brothers fell out spectacularly. Lawsuits followed. John Harvey clung to his Sanitarium and his principles; Will built a food empire.

In the end, history rewarded sugar. The Sanitarium burned down in 1942 and was never rebuilt. But Kellogg’s Corn Flakes remained.

And with it, an entire industry built on the bones of a spiritual movement.

Though the Battle Creek Sanitarium is long gone, its blueprint quietly lives on. Many of today’s wellness retreats—from luxury detox spas to New Age healing centers—still follow the model Kellogg helped invent: regimented diets, nature immersion, hydrotherapy, and the promise of spiritual renewal.

Just like at Battle Creek, health is often framed not just as a physical state, but as a moral achievement. And while the theology is gone, the structure remains—many modern retreats still mix fringe science, charismatic authority, and ritualized routines that blur the line between healing and belief.

Epilogue: From Sin to Cereal – Then and Now

John Harvey Kellogg may have preached colon cleansing and cereal-based salvation, but he wasn’t a vegan by modern standards. He allowed dairy, promoted yogurt for digestive health, and wasn’t motivated by animal rights. His crusade was about something older—and stranger. He believed dietary purity could stamp out lust, sin, and moral decay.

That theology still echoes today.

Modern nutrition discourse may not mention sin, but it still flirts with the idea of moral failure. We call foods “clean” and “dirty.” We speak of “guilt-free” eating. We demonize ingredients not just for their metabolic effects, but for what they seem to say about us as people. A ribeye becomes suspect. A sugary granola bar—blessed by health halos—passes as virtue.

This is the strange continuity between Kellogg’s sanitarium and today’s Instagram feed. One was a temple of fiber and repentance. The other is a glowing grid of smoothie bowls and self-discipline. But both are animated by the same question: What kind of person are you, based on what you eat?

Though the Sanitarium is gone, its spirit lives on. Our language around food still echoes Kellogg and Graham:

- We praise “clean eating”

- We moralize meat consumption

- We associate vegetarianism with discipline and virtue

- We view processed foods as sinful temptations

We often tell ourselves we’re making science-based choices. And sometimes we are. But other times, we’re echoing the old gospel of dietary salvation: avoid the impure, follow the light, cleanse the body, and you’ll be redeemed.

In truth, science and religion each have their place. The problem arises when we mistake one for the other—or worse, when we smuggle one inside the other, unknowingly.

The next time someone tells you to “eat clean,” ask yourself: Is this nutrition advice—or a sermon?

Portions of this article were developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model by OpenAI, to help refine structure, language, and clarity while preserving the author’s voice and scientific integrity.

Thank you for your article. As someone connected to the Adventist church from whom Dr. Kelllog learned basic principles about healthful living from the writings of a visionary pioneer (Ellen WHite), I feel that your perpective is undestandable and to be expect.

But I fundamentaly disagree on the issue of separation of science and religion as two friendly or unfriendly orbits. Science is ready to discredit the mind, just like psychoneuroimmulogy was at first seen with skepticism by the medical community.

THe biblical view of religion however views science and relgiion as different facets of the diamond. It is exactly this compartmentalization of things that have not let medicine embrace the influence of the body on the brain and mind, and vice versa. Graham was the first one to bring this up. Today with the amount of science that we know we can build a strong case for the idea that any indulgence of uncontrolled appetite reacts on mood. Annedotally this can be seen in the sugar blues and food coma.

Your version of Dr. Kellogg however is a someone deeply religious. But he was not. He was a moralist. And in your test you make it sound like self control is ‘Old school” . Of what? Science? relgiion? Morality? Psychology?

It will be years untill physicians undestand that “all things by immortal power hiddenly liked are, that you cannot stir a flower without troubling a Star”

In that day, medicine will not tell patients: “it’s all in your head” and things will appear with a clarity that will bring on the epiphany. Science is full of biases because it is written and interpreted by biased people.

Hi Wil,

Thank you for your thoughtful comment. I’m still reflecting on it—it touches on a number of ideas, and I’m doing my best to understand the full scope of what you’re saying.

One of the main purposes of the article was to explore how early health movements—like those influenced by Graham and Kellogg—shaped the way we still think and talk about food today, especially the moral language that shows up in modern diet culture.

I appreciate your perspective, especially around the integration of science, religion, and the mind-body connection. These are complex topics, and I value the chance to think more deeply about them.

Warm regards,

Axel