Estimated reading time: 19 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, Episode 10: When the Moon and Stars Fell on One Man, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

This is the 10th episode in The Heart of Power: Medical Histories from the White House, a series exploring the hidden and not-so-hidden health struggles of U.S. presidents.

Harry S. Truman is not the most talked-about president in American history. And unlike many of the others I’ve written about, he was remarkably healthy. No paralytic illness like Franklin Roosevelt. No massive heart attack like Dwight D. Eisenhower or Lyndon B. Johnson. No Addison’s disease hidden behind a tanned smile like John F. Kennedy.

For a time, I wondered if I should write about him at all. What is there to say about a man whose body never betrayed him?

But the more I read, the more I realized: Truman’s story is not about hidden disease. It is about something else entirely — the weight of decisions, the physiology of stress, and the ordinary heart that carried the dawn of the atomic age.

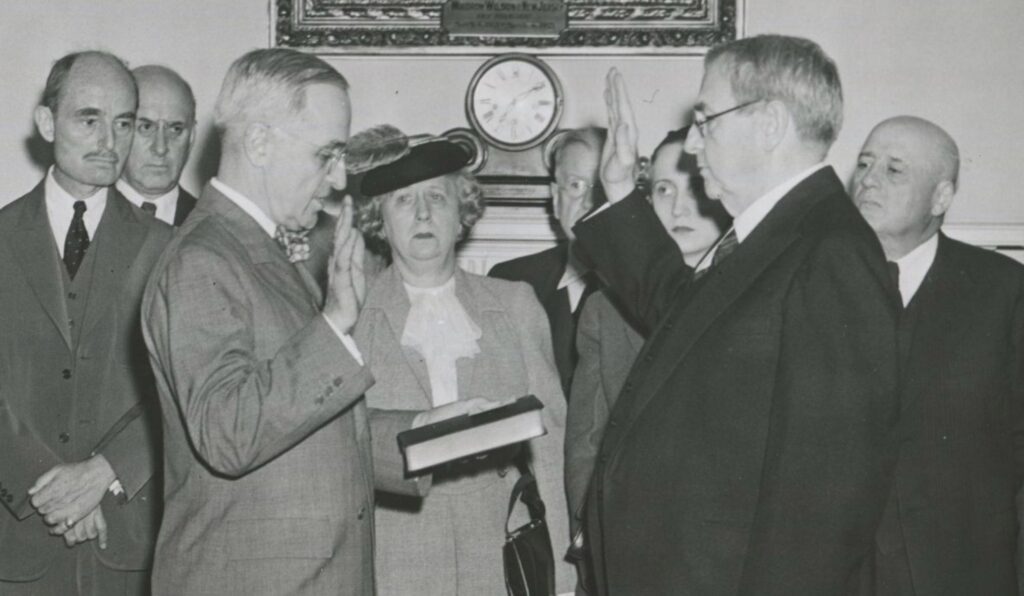

It was late afternoon, April 12, 1945. Harry Truman had just settled into his Senate office when the phone rang. He was told to come to the White House at once.

When he arrived, Eleanor Roosevelt was waiting. Her face was pale, her words simple: “Harry, the President is dead.”

Truman staggered. “Is there anything I can do for you?” he asked.

Eleanor shook her head. “Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.”

The words hit harder than any diagnosis. Truman was sixty years old, a failed haberdasher turned senator, vice president for just eighty-two days, and suddenly commander-in-chief in the final, brutal months of World War II.

Unknown to him until that moment, Roosevelt had never told Truman about the Manhattan Project. Only after he was sworn in did Secretary of War Henry Stimson and General Leslie Groves reveal the secret: America possessed a weapon so destructive it could end the war — and redefine humanity’s future.

Truman later wrote, “It seemed to me that the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.”

Doctors might have called it nervous strain. Today, we’d say adrenaline, cortisol, and blood pressure spiking. But this was not a case for medicine. It was history pressing down on the chest of an ordinary man.

And within weeks, he would face the most terrible decision any president had ever faced.

A Man of Flesh and Glasses

Harry Truman never looked like destiny. He was born in a farmhouse near Lamar, Missouri, in 1884 — the son of a mule trader and a farmer’s daughter. Poor eyesight plagued him from childhood; by age ten he was squinting so badly he needed the thick round spectacles that became his lifelong trademark. They magnified his eyes and gave him the look of a bookish clerk rather than a future commander-in-chief.

But behind the glasses was discipline. He rose at dawn to work the farm, memorized long passages of history and scripture, and read by the dim light of a kerosene lamp. He was no natural athlete, no soldier’s soldier, but he was persistent.

His health was, for the most part, unremarkable. He didn’t smoke heavily. He drank modestly — bourbon in the evenings, but rarely to excess. He walked briskly, sometimes almost trotting, through the streets of Washington with his bowler hat tipped and his cane tapping against the pavement. His White House physician, Dr. Wallace Graham, described him as a man of “sturdy constitution.”

Unlike Roosevelt, Eisenhower, or Kennedy, Truman’s file held no dramatic diagnosis. His vulnerability was not in his body but in his plainness.

And yet, that plainness was the paradox. Because this seemingly ordinary man — whose only visible frailty was a pair of thick spectacles — now carried the secret of the most terrible weapon in history.

The Briefing: A New Weapon

On his second day as president, Harry Truman sat in the Oval Office with Secretary of War Henry Stimson and a broad-shouldered general named Leslie Groves. The men carried a file that looked ordinary enough, but its contents were anything but.

They told Truman about a project so secret even he, the vice president of the United States, had been excluded from it. “For three years, scientists worked in hidden labs and fenced company towns — cut off from the world — to build a weapon no one had ever seen.

The terms were technical: uranium, plutonium, fission. But the meaning was unmistakable. A single bomb, they said, could destroy an entire city. One plane, one bomb, one city — gone.

He listened without interrupting, hands folded, glasses perched low on his nose. Later he would confess the revelation left him reeling.

That night, in his diary, he wrote: “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world. It may be the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley Era, after Noah and his fabulous Ark.”

He was only days into the job, and suddenly the steward of a weapon that seemed torn from the Book of Revelation.

And before long, he would have to decide whether to use it.

The Decision to Drop the Bomb

By the summer of 1945, the war in Europe was over. Hitler was dead, Berlin in ruins. But Japan fought on — with kamikaze pilots, suicidal defenses on tiny islands, soldiers who chose death over surrender. American generals came to Truman with projections: an invasion of the Japanese mainland might cost half a million American lives, maybe more.

The meetings were heavy with cigarette smoke, ashtrays overflowing as men bent over maps and casualty charts. They spoke in the flat language of war planners — “operations,” “objectives,” “estimates” — but the numbers they laid down were human lives.

There were alternatives. Some scientists urged a demonstration: detonate the bomb on an empty island, invite Japanese observers, show them what awaited if they resisted. Others warned it would waste the only two bombs ready for use — and what if the demonstration fizzled? Wouldn’t that embolden Tokyo to keep fighting?

Truman listened. He was not a scientist. He was a man of instinct, raised on a Missouri farm, now asked to choose between a bloody invasion and a weapon that might end the war in a single stroke.

In the margins, the civilian cost flickered but did not dominate. How many would die if an atomic bomb leveled a city? Tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands. But against the ledger of American boys who would never come home if the war dragged on, the balance tilted.

On July 25, Truman recorded in his diary that he had ordered the bomb used against “a purely military target.” But the reality was different. Hiroshima was a city of soldiers and civilians alike — families, schoolchildren, the elderly — none of whom had been given a say.

The decision was made. A farm boy from Missouri, in office less than four months, had just unleashed a weapon that would change the nature of war and peace forever.

And on a quiet Pacific morning in August, the world would see what his decision meant.

Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Aftermath

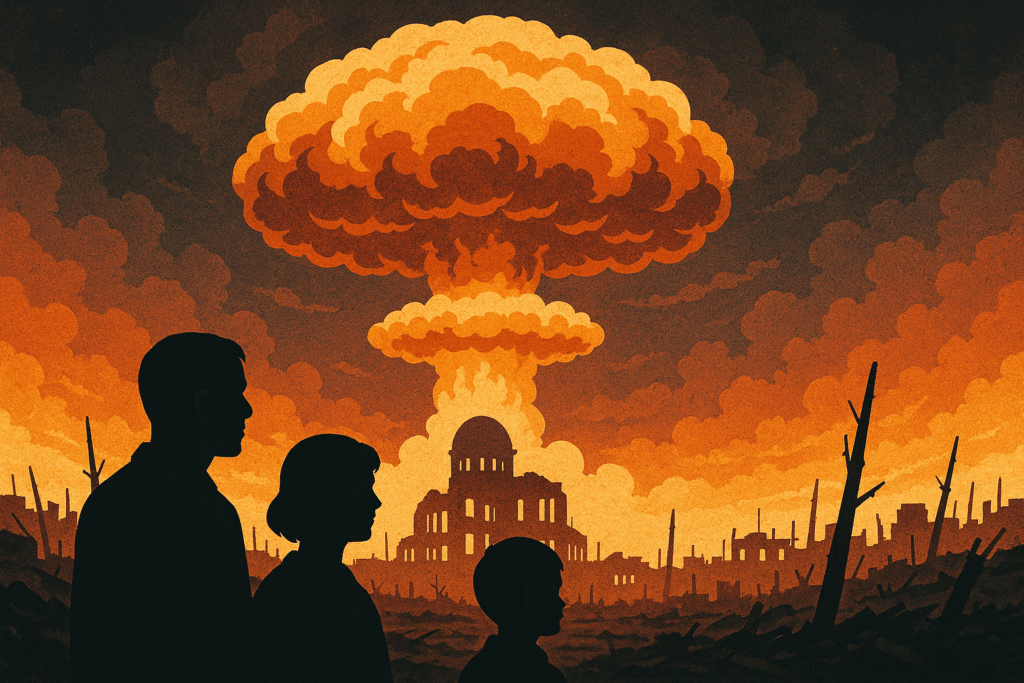

August 6, 1945. The sky over Hiroshima was a perfect blue. Another summer morning. At 8:15 a.m., the Enola Gay dropped a single bomb.

It fell for 43 seconds. Then the world split open.

A flash brighter than the sun. Shadows of men, women, and children burned into steps and walls. At the center, people vanished — no body, only a dark outline left behind. Houses burst into flames. The city was fire.

Seventy thousand dead before nightfall. Survivors stumbling, skin peeling off in sheets. Eyes sealed shut. Throats scorched, voices rasping only one word: water. Children wandering alone, calling for mothers who would never answer.

Three days later came Nagasaki. The target was Kokura, but smoke covered it. By chance, the bomb turned south. “Kokura’s luck,” they called it later. Nagasaki had none. Forty thousand gone in seconds. By year’s end, seventy thousand more.

And then the sickness. Not from fire. From something invisible. Hair falling out in clumps. Mouths bleeding. People who had walked away collapsed days later, burning with fever, bleeding inside. Doctors had no name for it. They had never seen the body consumed this way.

By December, more than 200,000 Japanese were dead from the two bombs. In the years that followed, the cancers came. Leukemia. Tumors. A shadow across generations.

The weapon didn’t just kill cities. It rewrote medicine.

The world reacted with awe and horror. American newspapers hailed the bomb as a miracle that ended the war, saving untold American lives. Winston Churchill called it “the Second Coming in Wrath.” Pope Pius XII denounced it as “a weapon against humanity itself.” Across the globe, the mushroom cloud became both a symbol of victory and a harbinger of annihilation.

Two months later, a visitor came to the Oval Office: J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who had directed the scientific core of the Manhattan Project. The newspapers had already called him the “father of the atomic bomb.”

But when he faced Truman in October 1945, Oppenheimer looked less like a father of triumph than a man undone by his creation. His face was gaunt, his voice subdued.

“Mr. President,” he said quietly, “I feel I have blood on my hands.”

Truman’s jaw tightened. The words infuriated him. Later he snapped to an aide, “Never bring that crybaby in here again.” The blood, Truman insisted, was his responsibility alone. He had made the call.

And in making it, he bound the human heart to the nuclear age.

The Man Who Carried the Buck

Harry Truman was never supposed to be here. He was the compromise choice for Roosevelt’s fourth-term ticket, picked because the party bosses thought he was safe and ordinary. They were right — and wrong. He was no patrician statesman, no soaring orator. He was a farm boy from Missouri who once went bankrupt selling men’s shirts and neckties.

He carried himself with a neatness that bordered on stiff. Crisp suits, a bow tie just so, a brisk walk with his cane tapping the sidewalk. But beneath the tidy exterior was a man who swore easily, lost his temper quickly, and never pretended to be anything he wasn’t. Once, when a critic mocked his daughter Margaret’s singing, Truman fired off a letter promising, “I have never met you, but if I do, you’ll need a new nose.” That was Truman — proud, volcanic, unvarnished.

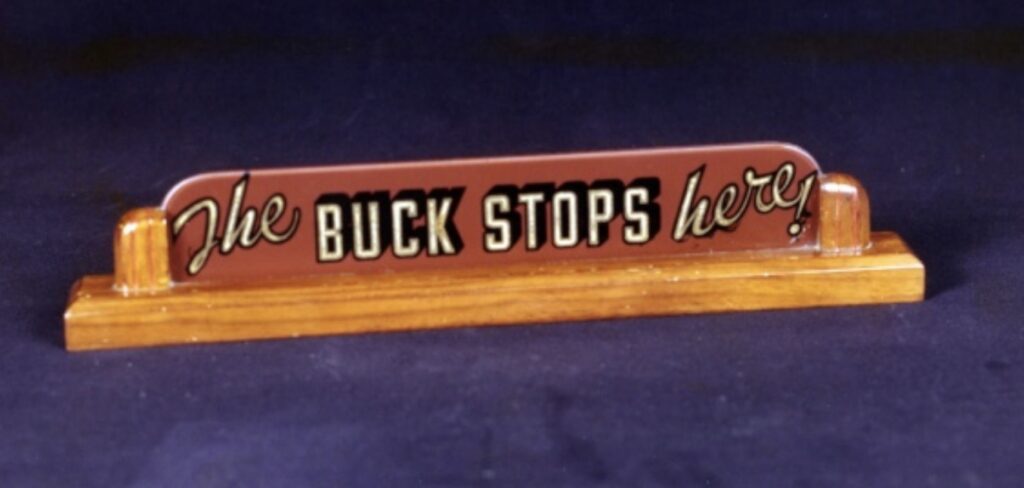

On his desk sat a small sign: “The buck stops here.” It was not decoration. It was the whole of his political philosophy in four words. No commissions, no passing the blame. Once a problem reached him, he owned it — for better or worse.

That creed made him decisive, even brutal. He ordered the atomic strikes and never apologized. He fired Douglas MacArthur, the most celebrated general in America, because he would not tolerate insubordination. He recognized Israel against the advice of nearly everyone around him. When Truman made up his mind, there was no shifting him.

Unlike Roosevelt, he did not rule from a wheelchair. Unlike Eisenhower, he did not live with a damaged heart. His body never betrayed him. What defined Truman was the edge of his character — blunt, irritable, sometimes crude, but anchored by a stubborn certainty that he could carry whatever history put on his desk.

An ordinary man, yes. But ordinary men are not supposed to carry the fate of continents in their breast pocket. Truman did, and he never flinched.

The war was over, but peace was already unraveling. The next confrontation would not be fought with bombs dropped from silver planes. It would begin at a long wooden table, across from a mustached man who never blinked.

And his name was Joseph Stalin.

Facing Stalin at Potsdam

In July 1945, just a few weeks before the Hiroshima bombing, Truman boarded a plane to Germany for his first summit as president. The destination was Potsdam, a suburb of Berlin that still smelled of smoke and rubble. Whole blocks of the city were flattened, streets turned to gravel, bricks stacked like broken teeth.

Across the table sat Joseph Stalin. Stocky, mustached, expression carved from stone. He smoked his pipe slowly, as if every puff was a warning. Roosevelt had charmed him, Churchill had sparred with him. Truman had neither the pedigree nor the practice. He was the new man at the table, and everyone knew it.

But Truman had something Roosevelt never lived to see: the bomb. Just days earlier, in the desert of New Mexico, the Trinity Test had lit the night sky with a fireball that turned sand into glass. Oppenheimer quoted the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Truman didn’t quote scripture. He just knew America now had a card no one else could play.

He leaned toward Stalin and mentioned, almost casually, that the United States possessed “a new weapon of unusual destructive force.” Stalin nodded, puffed his pipe, and said little. Truman thought he had startled him. In truth, Stalin already knew. His spies had been inside the Manhattan Project for months.

After that exchange he carried himself differently—quicker step, firmer voice. What medicine calls adrenaline did the rest, tightening muscles across from Stalin.

But if he thought it gave him the upper hand, he was wrong. Stalin wasn’t shaken. He was already preparing to build his own. The Cold War didn’t begin with speeches or treaties. It began here, in a half-bombed German villa, where two men eyed each other across a table and each understood that the other would not back down.

The war was over. The standoff had begun.

The Cold War Presidency

The war ended with mushroom clouds, but peace never came. Truman barely had time to catch his breath before the next fight began.

In March 1947 he stood before Congress and announced what became the Truman Doctrine: America would defend “free peoples” against communism everywhere. The words were lofty, the meaning blunt. The United States had appointed itself the world’s policeman.

A year later came the Marshall Plan. Billions of dollars flowed into Western Europe — food, fuel, steel — enough to keep factories humming and lights on in cities still scarred by war. It was aid, but it was also strategy: hungry nations drift toward extremism. Truman wanted them anchored to the West.

Then came Berlin. In June 1948, Stalin cut off the city, sealing the roads and rails that fed two million people. Truman answered with planes, not tanks. For nearly a year, American and British pilots dropped food and coal from the sky, nearly 300,000 flights in all.

Stalin blinked first. The blockade ended.

But the months of tension — watching day after day whether the flights would fail, whether Berlin would starve — weighed heavily. For most men, chronic stress means ulcers, sleepless nights, blood pressure creeping higher. For Truman, it became routine. His physicians noted no breakdown, but no chart can capture the strain of waiting for a city to suffocate.

Victories never held long. In 1949, the Soviets tested their own atomic bomb. The monopoly was over. Months later, Mao’s revolution in China placed a quarter of humanity under communist rule.

And then came Korea.

June 1950: North Korean tanks smashed across the 38th parallel, swallowing Seoul in days. Truman called it a “police action,” but it was war — the first of the nuclear age. American soldiers froze and died in the hills. When Chinese troops poured across the Yalu River, the conflict became a nightmare.

General Douglas MacArthur demanded escalation, even nuclear strikes. Truman refused. When the general pressed on, Truman fired him. The country erupted. Veterans booed, newspapers howled, politicians called him weak. To fire America’s most celebrated commander felt like betrayal.

Truman never flinched in public, but the anger cut deep. Letters poured into the White House, some praising him, most damning him. He carried on, stubborn as ever, shoulders squared against the storm.

At night, his staff noticed the signs: fatigue, irritability, bursts of temper. What we would now call stress-induced insomnia. Doctors still called it a sturdy constitution. But the nervous system tells its own story, whether or not the physician writes it down.

And even as he stared down Stalin abroad, a new enemy was rising at home — one armed not with bombs, but with accusations.

McCarthyism: The Cancer Within

While Truman stared down Stalin abroad, another battle was brewing at home. This one had no tanks, no bombers, no front lines. It had a microphone and a name: Joseph McCarthy.

In February 1950, the little-known senator from Wisconsin stood in Wheeling, West Virginia, and waved a sheet of paper. He claimed it held the names of 205 communists working inside the State Department. The number shifted by the week — 205, 81, 57 — but precision didn’t matter. Fear did.

The accusations spread like wildfire. Professors, teachers, civil servants, screenwriters — all dragged under suspicion. Careers ended overnight. Hollywood actors were blacklisted. Even generals weren’t safe. People whispered in offices and neighborhoods, wondering who might be next.

Truman despised McCarthy. He called him a “ballyhoo artist,” a con man feeding on paranoia. But the senator had tapped into something darker — the fear that communists were not just out there, in Moscow or Beijing, but right here at home. To question McCarthy was to risk being labeled a traitor yourself.

For the nation, it was like an autoimmune disease: the body turning on itself, mistaking its own cells for enemies. Democracy consuming its own trust.

Even the men who had built the bomb were not spared. J. Robert Oppenheimer — who had once stood in Truman’s office and whispered about blood on his hands — found himself accused of disloyalty. In 1954, his security clearance was revoked after a humiliating public hearing. The father of the atomic bomb was cast out by the country he had armed.

Truman tried to stand above it, but the poison seeped everywhere. Loyalty oaths spread through government. The FBI swelled with files. Neighbors eyed each other with suspicion. McCarthy’s star rose as Truman’s presidency sank under the weight of war in Korea and the politics of fear at home.

When Truman left office in 1953, his approval rating hovered at 22 percent — lower than Nixon’s at the end. He walked out of Washington battered, unpopular, nearly broke.

Yet he was intact. The country he left behind was less so.

The Cold War would go on for decades, but Truman’s fight with McCarthy showed how fear could wound a democracy from the inside out.

The Ordinary Longevity of an Extraordinary Life

When Truman left Washington in January 1953, there were no parades. No victory lap. His approval rating was in the gutter. He boarded a train back to Missouri with Bess at his side, their luggage modest, their bank account nearly empty.

He went home to Independence and slipped back into ordinary life. He took morning walks through town, waved to neighbors, wrote letters in longhand, and cursed the new White House occupant under his breath. He had no Secret Service protection for years. Tourists sometimes showed up at his front door; Bess would open it herself.

Age came for him slowly. His eyesight dimmed, his steps shortened, but the man kept moving. He lived simply, ate plainly, and never pretended he wanted more. A bourbon in the evening. A book before bed. He liked history, especially the parts where men had to make hard choices.

By the 1960s, the world had changed again. Eisenhower had his heart attacks. Kennedy was assassinated. Johnson drowned in Vietnam. Nixon unraveled on live television. And Truman, the accidental president, just kept going. Ordinary meals, ordinary days, stubborn as ever.

He lived almost to eighty-nine. In December 1972, pneumonia finally pinned him down. His organs failed. The man who had carried the decision to drop the bomb, who had stared down Stalin, who had outlasted McCarthy — slipped away quietly in a Kansas City hospital.

He was buried in Independence, not in Arlington. Just another American grave. No grandeur, no marble rotunda. A plain marker for a plain man.

Harry Truman didn’t outlive history. He carried it. His body held. His conscience never wavered.

That was his diagnosis. That was his legacy.

If you enjoy DocsOpinion’s articles, you may also like my Substack newsletter — shorter reflections, serialized essays, and behind-the-scenes notes on medicine, history, and science.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Next in The Heart of Power

He ruled from a broken body.

She performed through pills and pain.

Their lives touched in secret — and the rumors never died.

John F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe — two fragile icons, both unwell, both doomed.

Previous:

Episode 1. The Heart of Power: When Metabolic Disease Entered the Oval Office – William Howard Taft

Episode 2. The Heart of Power: The Golf Course Heart Attack – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Episode 3. The Heart of Power: The Stroke That Silenced a Dream – Woodrow Wilson

Episode 4. The Heart of Power: Built To Stand, Bound To Fall – John F Kennedy

Episode 5. The Heart of Power: Where Strength Sat Still – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Episode 6. The Heart of Power: The Ride Into the Sunset – Ronald Reagan

Episode 7. The Heart of Power: The Enemy Inside – Richard M Nixon

Episode 8. The Heart of Power: The Ticking Man – Lyndon B Johnson

Episode 9. The Heart of Power: The Doctor Who Knew Too Much – George G Burkley

📚 Sources & Further Reading

-

- Truman, H.S. Memoirs: Year of Decisions, 1945. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1955.

- Ferrell, R.H. Harry S. Truman: A Life. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1994.

- McCullough, D. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- Alperovitz, G. The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

- Sherwin, M.J. & Bird, K. American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

- Bernstein, B.J. “Truman and the A-Bomb: Targeting Noncombatants, Using the Bomb, and His Defending the Decision.” Journal of Military History. 1995;59(1):119–150.

- Hasegawa, T. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

- Walker, J.S. Prompt & Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

- Hamby, A.L. Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Offner, A.A. Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War, 1945–1953. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002.

- McCullough, D. The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

- Fried, R.M. Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Griffith, R. The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1987.

- Graham, W. “Medical Observations on President Harry S. Truman.” In: Ferrell RH, ed. Dear Bess: The Letters from Harry to Bess Truman, 1910–1959. New York: W.W. Norton, 1983.

- Sapolsky, R.M. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. 3rd ed. New York: Henry Holt, 2004. (for physiological discussion of stress hormones, cardiovascular strain).

Some portions of this article were developed with support from ChatGPT, an AI tool created by OpenAI. It was used to assist with research synthesis, narrative structure, and language refinement. All medical content, historical analysis, and editorial decisions were independently reviewed and finalized by the author.