Share this post:

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

You can listen to this article — The Echo Chamber of Cardiology — narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

Just days ago, something remarkable happened.

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary stood at a podium and said what would’ve once been unthinkable.

“That dogma still lives large,” he declared, referring to America’s decades-long war on saturated fat. “You see remnants of it in the food guidelines that we are now revising.”

It wasn’t just a revision. It was a rebuke.

Makary didn’t mince words. He called the foundational science behind decades of dietary advice—especially Ancel Keys’ Seven Countries Study—“incomplete and methodologically flawed.” He accused the medical establishment of “locking arms and walking off a cliff,” chasing a seductive theory about fat while ignoring the more insidious drivers of cardiovascular disease: sugar, refined carbohydrates, and the inflammation they unleash.

Makary is not a cardiologist or a nutrition scientist—he’s a surgeon and a professor of health policy at Johns Hopkins. His surgical achievements include advances in minimally invasive pancreatic procedures and innovations in patient safety. Some see his outsider status as a liability. Others view it as a strength: someone unbound by decades of institutional orthodoxy, willing to question what others won’t. Either way, the weight of his critique is impossible to ignore.

What Makary said wasn’t new. But the fact that he said it—publicly, as head of the FDA—was.

And it brings us to an uncomfortable truth:

The war over dietary fat never really ended. It just went quiet.

To understand why we’re still fighting, we have to go back to where it started—when heart disease surged unexpectedly and the scientific world scrambled to explain it. That’s when diet became the focus, and the stakes became global.

Was it fat? Was it sugar? Was it both—or neither?

Answering that question led into uncertain territory, where urgent questions met limited evidence, and bold hypotheses quickly became public doctrine. This wasn’t just a scientific disagreement. It became a war of beliefs, reputations, policies, and consequences we’re still living with today.

And so often, science turns on character. Today, it’s Makary. Decades ago, it was two men who defined the argument—and each other. To truly understand how this all began, I will revisit the lives, views, and interactions of two deeply influential figures from the last century: Ancel Keys and George Mann.

The Epidemic No One Saw Coming

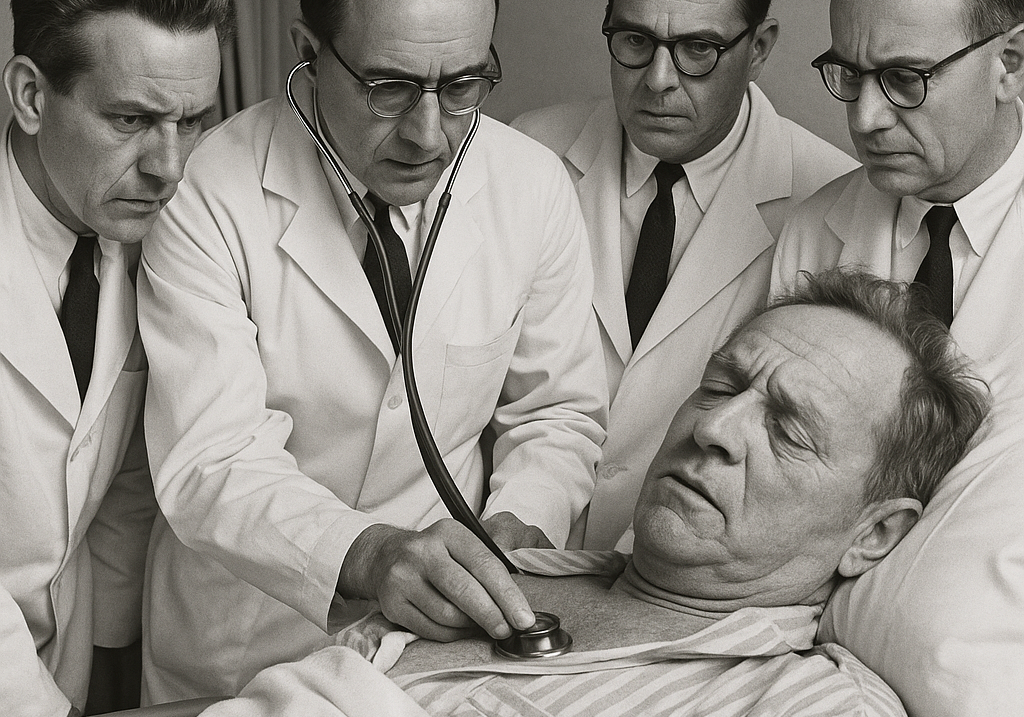

It began quietly. Middle-aged men—fathers, workers—were collapsing without warning. Not from infection, trauma, or old age. This was something new. A tightness in the chest. Shortness of breath on the stairs. A numb arm at midnight. Then, sometimes, nothing at all, just sudden death.

In the decades after World War II, coronary heart disease emerged as the leading cause of death in the Western world. And no one was prepared.

There were no statins. No stents. No CT scans or preventive clinics. Cardiologists were rare. Most heart attacks were either missed or diagnosed too late. It was an epidemic unfolding in real time—under the radar of a profession trained to think in terms of infection and injury.

Autopsies told a chilling story: arteries narrowed and scarred, choked with pale yellow plaques like wax lining a pipe. But what caused the buildup? Why now? Why here, in the most affluent societies on earth?

Was it lifestyle? Stress? Industrial food?

One thing was clear: something in the modern environment had changed.

Into that moment of fear and confusion stepped two men with two very different answers.

Ancel Keys, the driven physiologist from Minnesota, believed he saw the pattern. The culprit, he argued, was saturated fat—especially from meat, butter, and cheese. These foods raised blood cholesterol. Elevated cholesterol led to plaque. Plaque led to heart attacks.

George Mann, the maverick biochemist from Vanderbilt, saw something else. To him, the problem wasn’t fat at all. It was sugar, starch, and the hormonal chaos triggered by insulin. Keys, he believed, had the science wrong—and worse, the power to make his mistake global.

What followed wasn’t just a disagreement. It was a war of ideas—one that reshaped how the world eats and how millions live—or die.

Despite shaping decades of policy and public perception, Keys and Mann never sat across from each other on a stage or debated face-to-face.

Their conflict played out through journals, interviews, and rival studies—a war waged not with dialogue, but with data and defiance.

Yet even in silence, their clash changed everything.

They didn’t just shape the diet-heart debate. They became it—two starkly different visions of the same unfolding crisis.

And while neither man would fully win, their collision lit a fuse that would burn through decades of science, policy, and public belief.

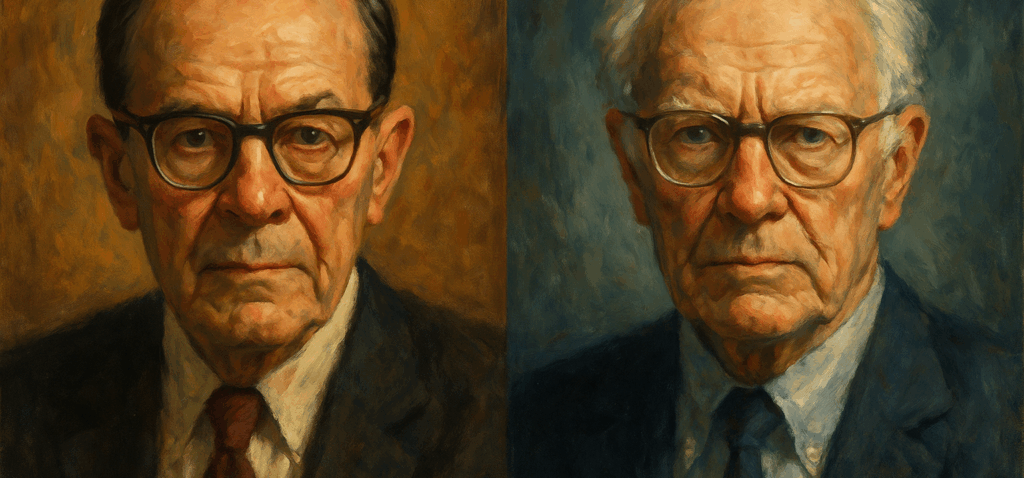

Despite their shared scientific stature and fierce convictions, Keys and Mann could hardly have been more different in character.

Ancel Keys was methodical, image-conscious, and deeply pragmatic. He was adept at navigating institutions, confident in front of cameras, and persuasive to policymakers. He built his arguments on broad patterns, long-term studies, and public messaging. Although forceful, he was often measured, more likely to dismiss critics than to engage in debate with them.

George Mann, on the other hand, was combative, blunt, and unfiltered. He distrusted consensus, challenged authority, and often blurred the line between scientific critique and personal attack. To many, he came across as brilliant but abrasive—a whistleblower to some, a heretic to others. Where Keys sought public health reform, Mann sought to blow the whole thing open.

And yet, both men lived long enough to see the scientific tide shift around them.

Ancel Keys died in 2004 at the age of 100. George Mann died in 2013 at the age of 96.

They didn’t just shape the diet-heart debate. They outlived it—each convinced, to the end, that history would vindicate their view.

This is the story of The Fat Wars: the scientific clash between Keys and Mann that launched dietary guidelines, shaped public health, and sparked a debate still raging in headlines, textbooks, and clinical practice.

Why tell it now?

Because the stakes remain. Cardiovascular disease is still the world’s leading killer. Nutrition science is still fractured. And in an age of ultra-processed foods, obesity, and public mistrust, one question still haunts us:

What if the original debate was never truly settled?

Round 1: Ancel Keys and the Urgency of Prevention

Ancel Keys wasn’t a cardiologist. He was a physiologist by training, a wartime scientist by experience—and a man obsessed with patterns.

In the postwar decades, Keys noticed something strange. Countries like the U.S. and Finland had soaring rates of heart disease. But in southern Italy, Crete, and Japan, the disease was rare.

What was different?

He believed the answer lay on the plate. The high-risk countries consumed more saturated fat from meat, butter, and lard. The low-risk ones consumed less.

To prove the link, Keys launched the Seven Countries Study, which tracked nearly 13,000 men over time. The results reinforced his suspicion: more saturated fat meant higher cholesterol and more heart disease.

From this, he built the diet-heart hypothesis:

Saturated fat raises blood cholesterol. Elevated cholesterol causes atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis causes heart attacks.

Critics balked. Keys doubled down.

“There’s no connection whatsoever between dietary fat and heart disease? That’s simply nonsense,” he said in 1961.

He wasn’t alone. Several studies in the 1960s and 70s appeared to back him:

- The Framingham Heart Study demonstrated that higher cholesterol levels are associated with an increased risk of coronary disease.

- The Oslo Diet-Heart Study found fewer recurrent heart events with a low-fat, high-polyunsaturated diet.

- The LA Veterans Study showed a reduction in heart events when saturated fat was replaced with vegetable oil.

- The Finnish Mental Hospital Study demonstrated a reduction in mortality associated with lower intake of saturated fats.

In 1961, Time magazine put Keys on the cover. He championed a Mediterranean-style diet, long before it became popular.

“We’ve never said all fat is bad,” he clarified. “But too much saturated fat raises cholesterol, which leads to heart disease.”

To Keys, this wasn’t theory—it was triage. He believed the evidence was strong enough to act, and delay was a risk the public couldn’t afford.

But for others, Keys had gone too far, drawing bold conclusions from uncertain ground.

Round 2: George Mann and the Case Against Consensus

George Mann wasn’t convinced.

A biochemist-physician and Framingham collaborator, Mann respected the urgency. He just didn’t trust the logic. The diet-heart hypothesis, he argued, leaned on correlations, not causation.

“The diet-heart idea is the greatest scientific deception of our times.”

Mann ran his own studies. He investigated the Maasai of Kenya, whose diet was rich in meat and milk, yet they had low cholesterol and almost no heart disease. He extended this work to Inuit and other high-fat-consuming populations with similar results.

To Mann, this was a direct refutation of Keys. The real issue wasn’t fat—it was refined carbohydrates and the metabolic havoc of insulin.

“Keys wants to believe it’s fat. He’s built his career on that. But science doesn’t move forward by clinging to dogma.”

Mann had evidence, too:

He pointed to the Minnesota Coronary Survey, a large, randomized controlled trial conducted in the late 1960s and early ’70s. It showed that replacing saturated fat with vegetable oil did lower cholesterol, but made no difference in heart attacks or deaths. To Mann, that was fatal to the hypothesis.

He also cited autopsy studies from the Korean War. Young American soldiers—some just 18 or 19 years old—already had signs of arterial plaque. This suggested that heart disease wasn’t simply the result of diet or lifestyle but might begin far earlier, driven by deeper metabolic or developmental factors.

And above all, Mann attacked the logic of the diet-heart hypothesis. Correlation, he argued, was not causation. Keys was cherry-picking countries, ignoring populations that didn’t fit the narrative, and using epidemiologic data to drive public health policy prematurely.

“Science advances through dissent. But in this case, dissenters are treated as heretics.”

Mann’s tone was combative. It cost him. He was sidelined—but never silenced.

In 1977, Mann published a scathing editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine titled “Diet-Heart: End of an Era.” In it, he called the diet-heart hypothesis a “public health experiment based on flimsy evidence,” and predicted it would ultimately collapse under the weight of better science.

“The hypothesis is not only unsupported by evidence but is often contradicted by it,” Mann wrote. “It has delayed the development of more promising approaches.”

The editorial sparked immediate backlash. For some, it was heresy; for others, a necessary correction. But Mann’s tone—direct, accusatory, and often personal—undermined its reception. As one historian put it:

“He typically ignored the tenets of good diplomacy by speaking loudly and carrying a big stick, and usually distinguished poorly between personal attack on colleagues and scientific criticism.”

Still, his fieldwork had impressed even his detractors. His studies among the Maasai and Mau Mau herders—populations with high-fat diets, low serum cholesterol, and rare heart disease—posed real questions that conventional epidemiology struggled to answer.

But Mann was no epidemiologist. He distrusted large observational data sets, favored direct biological evidence, and rejected what he saw as ideological groupthink. In that, he was both a thorn in the side of public health orthodoxy and a reminder of the value of dissent in science.

Mann didn’t rewrite the guidelines. He didn’t build a consensus. But he never stopped warning that the wrong convictions, held too tightly, could lead science astray.

To many, he was a crank. To others, a prophet.

And if he was loud, it’s because he believed the silence was more dangerous.

George Mann strongly challenged the diet-heart hypothesis. He believed the science was weak, the conclusions rushed, and the public misled. His style was confrontational, but his warnings about flawed evidence and premature consensus still matter today.

Round 3: Policy, Panic, and the Fat-Free Era

By the mid-1970s, a hypothesis had become a headline—and then a directive.

In 1977, the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, chaired by Senator George McGovern, released the first Dietary Goals for the United States. For the first time, the federal government wasn’t just warning about individual nutrients—it was telling Americans how to eat.

The message was clear: cut back on fat, especially saturated fat. Choose lean meats. Avoid butter. Replace whole milk with skim. Eat more grains and vegetables. Cholesterol-lowering, low-fat diets were no longer experimental; they were official.

McGovern acknowledged the evidence wasn’t perfect. But, he argued, public health couldn’t afford to wait.

“Senators don’t have the luxury that a research scientist does of waiting until every last shred of evidence is in,” he said.

That urgency carried weight. Heart disease remained the country’s leading killer. The image of middle-aged men keeling over at work or in their living rooms lingered in the public consciousness. Action was felt to be necessary, even if the science was still evolving.

However, translating theory into guidance is never a straightforward process. Behind the seemingly straightforward language of dietary goals lay a complex web of assumptions, substitutions, and compromises.

The food industry didn’t simply pivot overnight. It adapted strategically. Butter was demonized, so margarine was fortified and promoted as an alternative. Eggs became suspect, so breakfast cereal was positioned as a heart-healthy option. Full-fat dairy declined; shelf-stable low-fat yogurt and cheese products surged. But these weren’t simple swaps—they were engineered alternatives, often packed with emulsifiers, thickeners, and sweeteners to compensate for what had been removed.

It wasn’t a conspiracy. It was the natural logic of industrial food production: meet demand, cut costs, claim health. Manufacturers weren’t acting in bad faith. They were responding to cues, many of which were provided by official guidance and reinforced by the media.

“Low-fat” became a label not just of health, but of virtue. Entire product lines emerged to match the new aesthetic: SnackWell’s cookies, fat-free salad dressings, pasta with “no added fat.” Yet the fat that was removed was often replaced with sugar, starch, or synthetic fillers. What began as a public health directive evolved into a commercial movement—and then a cultural identity.

And the public followed. Not blindly, but earnestly. People wanted to eat better, live longer, and do the right thing. They bought margarine instead of butter. They skipped the yolk. They feared fat because they’d been told it was dangerous.

What they weren’t told was what would replace it.

The unintended consequences began to surface by the late 1980s. As fat intake declined across the population, carbohydrate consumption surged, especially in the form of refined grains and added sugars. Breakfasts once based on eggs and bacon gave way to orange juice and boxed cereal. Lunches skipped cheese and meat for low-fat yogurts, bagels, and pretzels. Calories stayed high. Satiety dropped. Glycemic loads soared.

And as the population dutifully followed the low-fat script, obesity rates began to climb. So did type 2 diabetes. Paradoxically, even as heart disease mortality fell—thanks in large part to better emergency care and advances in pharmacology—the metabolic foundations of cardiovascular risk worsened.

Mann and others like him had warned of this outcome. However, their concerns had been drowned out—not only by political consensus, but also by a public health culture that had come to fear dietary fat more than processed food itself.

Nutrition became ideology. Disagreement, even from credible scientists, was cast as irresponsibility. And the complexity of diet and disease was reduced to a single villain: saturated fat.

“We are conducting a nationwide diet experiment,” one critic later wrote, “but it wasn’t tested in clinical trials—it was tested on the public.”

At the same time, it would be unfair to claim the dietary shift had no positive effect. Public health efforts to reduce saturated fat consumption, combined with declining smoking rates and improved hypertension control, coincided with a significant decline in CHD mortality in the U.S., the U.K., and other high-income countries from the late 1970s onward.

Population-wide reductions in blood cholesterol levels have been documented in several countries, and modeling studies have estimated that dietary improvements have contributed significantly to the decline in cardiovascular deaths. In this light, the “experiment” was not without success, but its benefits were uneven, and its collateral effects on metabolic health were often overlooked.

The fat-free era had begun with a clear directive and a noble intent. However, it unfolded as a series of trade-offs—many of which were poorly understood, and some of which were potentially harmful.

And once public perception was shaped, it became difficult to undo. The damage wasn’t just metabolic—it was epistemological. Trust in nutrition science fractured. The space between public health and personal experience widened. And into that void rushed a thousand new diets, gurus, and counter-narratives.

The food pyramid may have been drawn in Washington. But its legacy was written across supermarket aisles, dinner tables, and medical charts for decades to come

Key Takeaway:

The low-fat guidelines of the 1970s were a well-intentioned public health response to a growing crisis. While they likely contributed to reductions in heart disease, they also helped reshape the food supply in ways that were not fully understood, replacing fat with refined carbs and sparking decades of nutritional confusion.

Round 4: Science Evolves, but Consensus Hardens

By the 1990s, the conversation began to shift—not with an admission of guilt, but with advancements in science.

The statin era delivered some of the most dramatic clinical evidence to date. Trials such as 4S, WOSCOPS, and LIPID demonstrated that lowering LDL cholesterol with statins reduces cardiovascular events and saves lives. But these were primarily secondary prevention trials—treating patients who had already been diagnosed with heart disease. For supporters of Keys, they still offered powerful validation: lowering cholesterol worked.

As Dr. William C. Roberts—longtime editor of The American Journal of Cardiology and a tireless proponent of the LDL hypothesis—famously put it: “It’s the cholesterol, stupid.”

With characteristically blunt clarity, Roberts meant that while diet debates swirl and methodologies evolve, the core mechanism remains: atherosclerosis is driven by elevated levels of apoB-containing lipoproteins, especially LDL. The biology was sound—even if the dietary roadmap that led us there had been flawed.

But critics pointed out an important caveat—these were drug trials, not dietary ones. They argued that the evidence didn’t necessarily support dietary fat reduction in the general population—especially as a preventive measure. The findings confirmed that LDL mattered, but they didn’t confirm that saturated fat was the cause, or that cutting fat alone could prevent disease.

Then came the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)—a massive, government-funded dietary intervention involving nearly 49,000 postmenopausal women. It was, in many ways, the dietary test Keys had long called for. But after nearly a decade, the results were sobering: the low-fat diet did not significantly reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, or overall mortality. The findings raised serious doubts about the strength of the diet-heart hypothesis and gave new weight to longstanding critiques.

Meanwhile, new epidemiologic tools began to reshape the landscape. A 2010 meta-analysis in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition challenged the link between saturated fat and coronary disease.

The PURE study, spanning 18 countries and more than 130,000 individuals, found that high carbohydrate intake—not fat—was associated with increased mortality, especially in low-income populations. The narrative had shifted.

No longer was it “fat bad, carbs good.”

Now, it was: context matters. Which fats? Which carbs? Which populations?

The simplifications that had once driven policy were unraveling in the face of better data.

And the most consequential chapter of the debate—how this conflict shapes the way we eat today—was just beginning.

By the early 2000s, the pillars of the old consensus were showing cracks—but no one quite knew what to replace them with.

Key Takeaway:

As science advanced, cracks began to appear in the old consensus. Statin trials proved that lowering LDL saves lives—but mostly in people who already had heart disease. Meanwhile, large diet studies failed to confirm that cutting fat alone prevents it. The message was no longer simple. Fat wasn’t always the enemy. Context, food quality, and metabolic nuance now mattered more than macronutrient dogma.

Epilogue: The Debate That Won’t Die

There was no final ruling. No victory parade. No scientific armistice.

The Fat Wars didn’t end. They faded—into habits, labels, guidelines, and assumptions. Into breakfast aisles and cholesterol panels. Into the quiet unease of patients still afraid of eggs and doctors still trained to count fat grams.

Ancel Keys changed the world. He was right about many things—that lifestyle matters, that food affects disease, that public health can’t afford to wait forever. But in boiling heart disease down to a single nutrient, he oversimplified a complex truth. His hypothesis became policy before it was fully proven. And once policy hardens, it resists correction.

George Mann was no savior. His critiques were often bombastic, his tone combative. But beneath the fire was a warning science should have heeded: that premature consensus can blind, that evidence must lead—not politics, not personalities, not the noise of institutional momentum.

What followed was not just a battle over nutrients—but a lesson in how medicine moves forward, and how easily it can get stuck.

Today, we know more. We know that atherosclerosis is driven by ApoB-containing particles. That insulin resistance worsens it. That inflammation, metabolic health, and food context matter far more than macronutrient purity. We understand heart disease as a network of forces—biology, behavior, environment—not a simple cause-and-effect.

And yet, the ghosts of the old war still haunt us.

Science has moved on, but messaging lags. Labels still carry the baggage of outdated fears. Policies still echo the compromises of the 1970s. And public trust—battered by decades of shifting advice—isn’t easily rebuilt.

That’s the real damage of dogma: not just that it may be wrong, but that it makes correction feel like betrayal.

So no, the debate didn’t die. But it did evolve.

Not into certainty—but into something better: a slower, messier, humbler conversation. One that asks more questions than it answers. One that no longer seeks heroes or villains—but evidence, context, and truth.

Because in the end, science must lead.

Not ego.

Not consensus.

Not the ghosts of a good story told too soon.

Only then can we hope to learn from the past—without repeating it.

🔎 Related Reading on DocsOpinion

References and Further Reading

- Keys A. Seven Countries: A Multivariate Analysis of Death and Coronary Heart Disease. Harvard University Press; 1980. Link

- Keys A, Menotti A, Aravanis C et al. The seven countries study: 2,289 deaths in 15 years. Prev Med. 1984 Mar;13(2):141-54. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(84)90047-1. PMID: 6739443. Link

- Jeremiah Stamler, David M. Berkson, Quentin D. Young, Howard A. Lindberg, Yolanda Hall, Louise Mojonnier, Samuel L. Andelman, Diet and Serum Lipids in Atherosclerotic Coronary Heart Disease: Etiologic and Preventive Considerations, Medical Clinics of North America, Volume 47, Issue 1,1963,Pages 3-31,

ISSN 0025-7125, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-7125(16)33615-X. Link - Framingham Heart Study. Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1951;41(3):279–281. Link

- Leren P. The Oslo diet-heart study. Eleven-year report. Circulation. 1970 Nov;42(5):935-42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.42.5.935. PMID: 5477261. Link

- The Los Angeles Veterans Administration Study. Dayton S, Pearce ML, Hashimoto S, Dixon WJ, Tomiyasu U. A controlled clinical trial of a diet high in unsaturated fat in preventing complications of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1969;40(1 Suppl):II1–II63. Link

- Finnish Mental Hospital Study. Turpeinen O, Karvonen MJ, Pekkarinen M, et al. Dietary prevention of coronary heart disease: the Finnish Mental Hospital Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1979;8(2):99–118. Link

- Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Leelarthaepin B, et al. Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from the Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968–73). BMJ. 2016;353:i1246. Link

- Skeaff CM, Miller J. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: summary of evidence from prospective cohort and randomized controlled trials. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55(1-3):173–201. Link

- Enos WF, Holmes RH, Beyer J. Coronary disease among United States soldiers killed in action in Korea: preliminary report. JAMA. 1953;152(12):1090–1093. doi:10.1001/jama.1953.03690120012004. Link

- University of Minnesota CVD Epidemiology Group. George Mann’s Editorial on Diet-Heart: “End of an Era” — A Reply. CVD History Archive. http://www.epi.umn.edu/cvdepi/essay/george-manns-editorial-on-diet-heart-end-of-an-era-a-reply/. Accessed July 20, 2025.

- De Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h3978. Link

- Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295(6):655–666. Link

- PURE Study. Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, et al. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390(10107):2050–2062. Link

- Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Pedersen TR, et al. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1383–1389. Link

- West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group (WOSCOPS). Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(20):1301–1307. Link

- Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(19):1349–1357. Link

- Roberts WC. The cause of atherosclerosis: the cholesterol hypothesis. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(4):426–432.

- Mann GV. Diet-heart: end of an era. N Engl J Med. 1977;297(12):644–650. Link

- McGovern G. Dietary Goals for the United States. Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, U.S. Senate; 1977. Link

- Ludwig DS, Willett WC, Volek JS, Neuhouser ML. Dietary fat: from foe to friend? Science. 2018;362(6416):764–770. Link

- Taubes G. Good Calories, Bad Calories: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom on Diet, Weight Control, and Disease. Knopf; 2007.

- Teicholz N. The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet. Simon & Schuster; 2014.

- Mozaffarian D, Ludwig DS. The 2015 US Dietary Guidelines: lifting the ban on total dietary fat. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2421–2422. Link

Some portions of this article were developed with support from ChatGPT, an AI tool created by OpenAI. It was used to assist with research synthesis, narrative structure, and language refinement.

Great article. Never heard of George Mann before. Amazing that those studies that revealed some pretty solid evidence were ignored. Now 50 years later, science is coming around. Mann did say truth would eventually win out.

Humans have had millions of years to acclimate to eating meat, eggs, milk, and thousands of years for whole grains. Now the body has to figure out how to live off of white flour, sugar, processed vegetable oils and huge amounts of salt.

People focus on feeding their pets much better food than they eat themselves.

Dr. Makary also has an opinion on statins. From his book “Blind Spots: What medicine gets wrong, and what it means for our health.”

“Several studies have shown that statins can lower one’s mortally. But why? It’s been assumed because it’s because they lower lipid levels. That may be true, but in reality we don’t know if it’s due to their lipid-lowering effect or their anti-inflammatory effect. It’s like the latter because statins have been shown to improve survival in people with normal lipoprotein levels.”

My comment: Note that some drugs that were quite effective at lowering cholesterol were found to have negative, or no effect, on total mortality risk.

Professor Abramson, a Harvard Medical School professor and physician:

“You can lower cholesterol levels with a drug, yet provide no health benefits whatsoever,” Abramson says. “And dying with a corrected cholesterol level is not a successful outcome in my book.”

Inflammation May Be the Root of Our Maladies (September, 2024)

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/16/opinion/inflammation-theory-of-disease.html?unlocked_article_code=1.Lk4.Vi7B.4LHRMYy0Thl7&smid=url-share

Excerpt:

Dr. Ridker is one of the scientists credited with building a new understanding of inflammation, specifically how it can lead to heart disease. In the mid-1990s, he noticed many of his patients had suffered strokes and heart attacks despite having normal levels of cholesterol — which was thought to be the primary cause of heart disease. He and his colleagues also noticed these patients had elevated markers of inflammation in their blood, and he began to wonder if the inflammation wasn’t a side effect but actually came first.

To parse out cause and effect, chicken and egg, Dr. Ridker and his team analyzed blood samples from healthy men who had agreed to be tracked over time. Their findings “changed the whole game,” Dr. Ridker said. Seemingly healthy people with elevated levels of inflammation went on to have heart attacks and strokes at much higher rates than their less inflamed counterparts. The inflammation indeed came first, meaning it wasn’t only a consequence of heart disease but also a risk factor for developing it.