Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

Tennis and golf are two of my favorite recreational sports.

Although the purpose of these activities is to provide breathing space and pleasure, nuisance tends to be hard to avoid. Hence, relaxation is frequently overtaken by eagerness, and amusement is replaced by frustration. In my case, this is particularly true for golf.

When I play too much (which is quite common), I often feel pain around the elbow. This can be quite tedious, and most of the time, rest seems to be the only cure.

Unfortunately, the repeated swinging of a tennis racket or a golf club may cause elbow pain, sometimes making it impossible to play. This is frequently due to an inflammatory phenomenon called lateral or medial epicondylitis.

Epicondylitis is a common disorder that affects men and women equally (1).

The Elbow Joint

The elbow joint is formed by the articulation of the distal end of the humerus in the upper arm and the proximal ends of the ulna and radius in the forearm. It allows for the flexion and extension of the forearm relative to the upper arm, as well as rotation of the forearm and wrist.

A network of ligaments surrounding the joint capsule helps the elbow joint maintain its stability and resist mechanical stresses (2).

Many muscles originate and insert near the elbow making it a common site for injury. Repeated strenuous striking against force (as when playing tennis or golf) may cause strain on the tendinous muscle attachments. This may lead to inflammation and pain around the elbow joint.

The epicondyles are bony prominences easily felt on the medial and lateral sites of the distal humerus, above the elbow joint. The tendinous origins of the muscles that flex and extend the fingers are located at the medial and lateral epicondyle respectively (2).

When we extend the elbow with the palm of the hand facing forward, the lateral epicondyle is in line with the thumb, whereas the medial epicondyle is in line with the little finger.

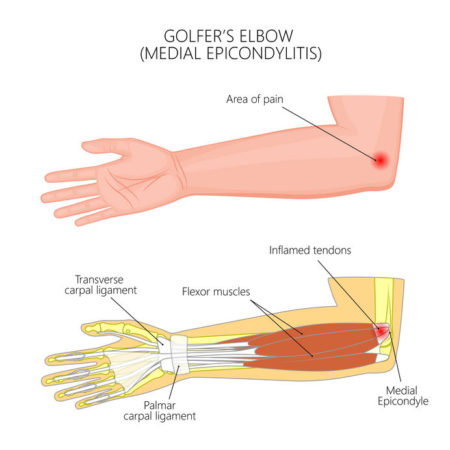

Tennis elbow is characterized by inflammation and pain located at the site of the lateral epicondyle whereas the pain from golf elbow is located at the site of the medial epicondyle.

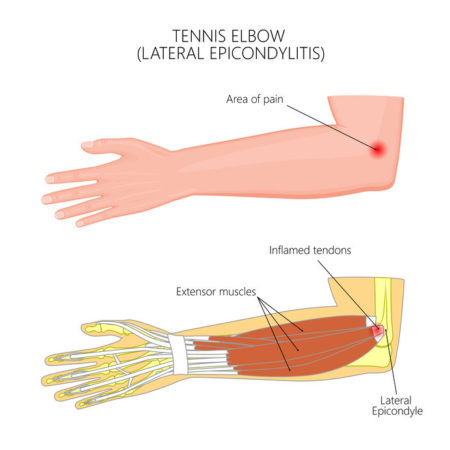

Lateral Epicondylitis (Tennis Elbow)

Pain around the lateral epicondyle is the most common type of elbow pain. It is most often caused by inflammation of the tendinous muscle attachments of the lateral epicondyle. Hence, the term lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow).

Lateral epicondylitis is caused by repetitive strain to the extensor tendon, notably extensor carpi radialis brevis, or by forced extension or direct trauma to the lateral epicondyle (1).

Lateral epicondylitis is common among tennis players, hence the term ‘tennis elbow’. Novice players with a one-handed backhand typically suffer from the disorder.

Other risk factors are poor swing technique, a heavy racket, incorrect grip size, and high string tension (4).

Many experts believe that the use of a one-handed backhand may increase the risk of lateral epicondylitis compared with a two-handed backhand (5).

Despite being termed “tennis elbow”, lateral epicondylitis is also common among golfers.

Lateral epicondylitis is also an occupational hazard among carpenters, gardeners, dentists, and politicians. This is due to repetitive wrist turning or hand gripping, tool use, and frequent handshaking (3).

Several tests have been developed to diagnose lateral epicondylitis.

The “book test” is sometemes used to diagnose tennis elbow. It is performed by having the patient hold a book with the arm in full extension and palm facing down (pronation). A positive test is marked by pain at the lateral epicondyle (2).

Medial Epicondylitis (Golf Elbow)

Medial epicondylitis is provoked by frequent eccentric loads on the muscles that are responsible for forearm pronation and wrist flexion (1).

Medial epicondylitis is commonly referred to as “golf elbow” (or golfer’s elbow). However, approximately 90 percent of cases occur outside of sport participation (4).

The pain is located around the medial epicondyle, hence the term “medial epicondylitis”.

Medial epicondylitis is also known as “baseball elbow”, “suitcase elbow”, or “forehand tennis elbow”. It is common among occupational settings involving repeated forceful gripping during heavy labor.

Medial epicondylitis is less common than lateral epicondylitis. It is most common in the 45- to 64-year-old age group. Women are more likely than men to suffer from the disorder, and three of four cases involve the dominant arm (6).

Elbow injuries, in general, are common among amateur and professional golfers. Interestingly, despite the term “golfers elbow”, lateral elbow injuries are more common among golfers than medial injuries.

In golfers, medial elbow injuries are thought to result from traction-based insults to the elbow during the swing. These usually affect the trailing arm (right elbow in the right-handed golfer).

Poor swing techniques may increase the risk of insults to the elbow causing medial or lateral epicondylitis. Striking the ground or other obstacles or from hitting repeatedly out of long, thick rough may also increase the risk (6).

The golfer’s elbow test may be used to help confirm the diagnosis of medial epicondylitis.

A modified version of the book test can be used to diagnose medial epicondylitis. Instead of a book, the patient is asked to hold a 3- to 5-pound (1.4- to 2.4-kg) weight with the arm raised, elbow fully extended, and palm facing upward. Discomfort at the medial epicondyle while holding the weight marks a positive test (5).

Treatment

Lateral and medial epicondylitis are self-limiting conditions, meaning that they will eventually get better without treatment. However, symptoms may sometimes last for weeks months which may be quite frustrating.

Resting the arm and stop doing the activity that caused the problem is a key issue. Hence, if you have tennis elbow, you may have to avoid playing tennis or stop carrying out manual tasks that may have caused the problem in the beginning. Alternatively, you may be able to modify the way you perform these types of movements so they do not place strain on your arm.

For athletes, the correction of faulty techniques is essential. Proper tennis stroke techniques can minimize the risk of elbow tendinopathy. In one study, instruction and stroke modification added to conservative therapy improved symptoms in 90 present of tennis players (7).

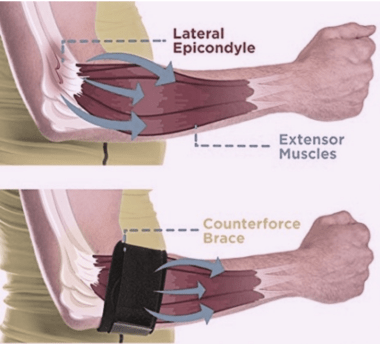

Bracing and Taping

Counterforce bracing is frequently used to treat lateral and medial epicondylitis.

This method applies pressure to the tendon origins of the forearm muscles, thereby reducing the forces transferred to the tendons themselves.

Braces should be placed on the forearm 2-3 cm below the point of maximal tenderness.

Tapes that follow a similar principle may also be used. Kinesiology tapes are elastic stiffeners that are stuck to the appropriate place on the forearm (8).

Physical Therapy

Most clinicians recommend physical therapy to treat epicondylitis.

Several physical therapy programs are available. Many of them rely on eccentric and isometric strengthening of the muscles originating from the elbow.

Passive exercises and massage can also be used.

Medical Treatment

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to treat lateral and medial epicondylitis.

NSAIDs may reduce pain and improve function in the short term (9). However, these agents should be used with caution due to their potential side effects (10).

Topical NSAIDs (eg, diclofenac gel) have become popular for treating tennis elbow and golf elbow. However, studies on these agents are preliminary.

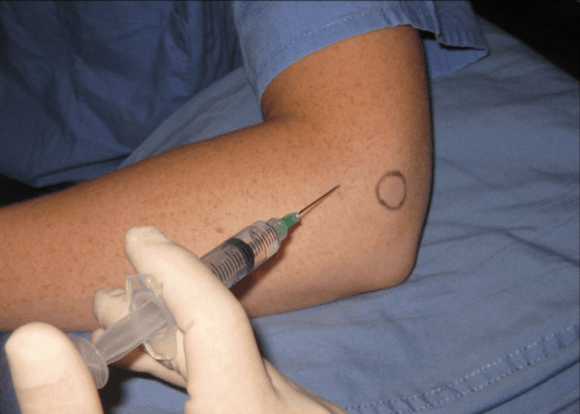

Some clinicians also use glucocorticoid injections into the area of pain. The objective of such conservative care is to relieve pain and reduce inflammation, allowing sufficient rehabilitation and return to activities (11).

Multiple trials show that glucocorticoid injections improve short-term measures but do not prevent recurrence and may lead to worse long-term outcomes (6).

Studies indicate that topical nitroglycerin (applied to the skin) may improve symptoms (12).

Acupuncture

Sometimes, acupuncture is used to treat epicondylitis. It may provide short term benefits but evidence fur a sustained benefit is lacking.

Botulinum Injection

Some clinicians use injections of botulinum toxin A into the are of inflammation. However, this is not standard treatment and should be used with caution due to potential risks.

Surgery

In most cases, lateral and medial epicondylitis can be managed without surgery. Hence, surgical intervention is not recommended unless symptoms include severe pain or marked dysfunction for six months or longer (6).

Surgery may involve cutting or releasing the inflamed tendon, removing inflamed tissue, and fixing tendon tears if possible (13).

Thank you for addressing this, Dr. Sigurdsson. I have found that the Theraband Flexbar has been helpful in reducing the discomfort and in relieving both lateral and medial epicondylitis. I have experienced both conditions, but luckily have found them rare now. I play golf, and I find that my age is a help through the maxim of “slowing down, hitting better”. A faster swing is the cause of poorer shots in my case and had been a contributor to elbow problems.

I think it’s “swing slower, hit better” — the advice to us older golfers by Butch Harmon, the celebrated American golfing coach.