Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

In-flight medical emergencies on commercial flights occur every day. In 2013, it was estimated that 44.000 such events occurred worldwide every year (1).

So if you are a doctor, a nurse, a medical student, an emergency medical technician or a person with first aid training, it is quite likely that one day your service will be needed in the skies.

The steadily increasing number of air travelers, the aging of the population, and the increasing number of air travelers with acute or chronic illnesses will undoubtedly increase the number of in-flight medical events in the future.

But, providing medical assistance in cramped quarters at 40.000 feet may not be an easy task. The low air pressure, the constant roar of the engine noise, and the presence of uninvited spectators will clearly not make the job easier.

However, understanding the essential nature of in-flight medical emergencies and some critical aspects of the aircraft environment will make us better prepared. Thereupon, this article is intended to answer important questions about in flight-medical emergencies and how they should be treated.

What are the most common causes of in-flight medical events? What is the proper way to respond? What medical resources are available on board the aircraft? Is expedited landing at the intended destination needed? When should a diversion to a closer location be recommended?

A Closer Look at the Statistics

There are about 5.000 aircraft in the sky at any given time, and the number of average daily scheduled passenger flights worldwide is approximately 26.500. In 2016, the number of scheduled passenger flights was 9.7 million (2).

More than 2.5 million domestic and international passengers fly every day. The estimated number of air travelers in 2016 was 3.6 billion. That’s about 800 million more than in 2011 (3).

In-flight medical events occur at a rate of 15 to 100 per million passengers with a death rate of 0.1 to 1 per million (4).

In 1998 – 1999, British Airways had 92 emergencies per million passengers (5). Of those, 70% were managed by cabin crew without the assistance of an onboard health professional.

It has been estimated that one in-flight medical emergency will occur in every 604 flights (4).

The Lufthansa Registry which contains data from the year 2000 onward documents a disproportionate increase in in-flight medical incidents in relation to passenger volume during the study period (6).

It has been estimated that a physician is present in approximately 40 percent of in-flight medical emergencies (7). However, these numbers have been shown to vary widely. The Lufthansa registry reports that in more than 80 percent of cases, a physician or other medical professional (e.g., nurse, emergency medical technician) gave help on board.

The Cabin Environment

Several medical issues may arise because of the general cabin environment and the nature of long-haul flights.

Turbulence may precipitate motion sickness and falling overhead items may cause injuries.

Long-distance flights may disturb circadian rhythm and disrupt the medication schedule of patients with chronic diseases.

The combination of inactivity and sitting with the legs down on the floor during air travel may cause blood to pool in the veins causing swollen feet and legs and even increase the risk of blood clotting (venous thromboembolism).

Cabin Pressure

The cruising altitude of commercial aircraft is usually maintained between 30.000 to 45.000 feet (9.100 to 13.700 m). The low atmospheric pressure at such heights is not compatible with survival. Therefore, aircraft cabins are pressurized during flight to the equivalent of 5.000 to 8.000 feet (1.500 – 2.400 m) above sea level.

Due to the lowered cabin pressure, the partial pressure of oxygen in cabin air at cruising altitude is 25-30% lower than at sea level. Although relatively well tolerated by most people, this may be problematic for some patients with hypoxia due to underlying heart-and lung conditions.

Because of the decreased cabin pressure, gases within body cavities will usually expand. The expansion of trapped gas may cause an earache because of swelling air in the middle ear, facial pain due to air in the paranasal sinuses, and abdominal pain due to distention of air in the intestine.

Cabin Air Quality

A part of the cabin air (no more than 40-50%) is recirculated and cleaned with special filters (HEPA), while the remainder is derived from the outside air (bleed air). The humidity on board ranges from 6-18% depending on the compartment (6). Optimal humidity varies between 40-70%. Hence, cabin air is arid.

The low humidity of cabin air can cause dry skin, dry eyes, and airways, sometimes triggering respiratory problems, especially in patients with asthma or chronic lung disease.

Insensible water loss in the dry cabin environment, combined with a low fluid intake on long flights, may cause dehydration although this is unlikely to cause symptoms in healthy individuals.

The air conditioning and ventilation system in a commercial aircraft can maintain low counts of microorganisms in the cabin. However, there are reports of individuals contracting a number of infectious diseases through airborne transmission (8, 9).

Airline Protocols For Managing In-Flight Medical Events

In the aircraft setting, the pilot, assisted by the co-pilot has overall responsibility for the passengers, the crew, the flight and the aircraft (10).

The cabin crew is responsible for managing in-flight medical emergencies. They are trained to recognize common medical problems and provide first aid and basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The cabin crew should make the initial assessment of the ill passenger and is responsible for informing the captain about the situation.

The crew may then request assistance from onboard medical professionals as needed. Furthermore, the captain may decide to call ground-based medical support (GBMS) for advice. In this way, specialists in aviation and emergency medicine may assist from the ground.

GBMS is now is now used by most large international carriers and by virtually all United States based airlines.

Based on the condition of the passenger the captain may determine to continue the flight plan but request medical assistance upon arrival, he/she can also request expedited landing at intended destination or decide to divert the aircraft to a closer location.

Common In-Flight Medical Emergencies

An extensive U.S. study of 11.920 in-flight medical emergencies published 2013 reported that the most common event was fainting (syncope) or near fainting (presyncope), representing 37.4 percent of all cases (1).

Respiratory symptoms were the second most common medical emergency (12.1%), and nausea and vomiting came third (9.5%).

Cardiac symptoms were present in 7.7%, seizures in 5.8%, abdominal pain in 4.1%, infectious diseasses in 2.8%, agitation or psyciatric symptoms in 2.4%, allergic reactions in 2.2%, possible stroke in 2.0%, trauma in 1.8%, diabetic complications in 1.6%, and headache in 1.0%. Cardiac arrest accounted for 0.3 percent of cases.

Aircraft diversion occurred in 7.3 percent of cases; the remaining flights landed at their scheduled destinations. Aircraft diversion was most likely to happen if the event was of cardiac nature, a seizure or a possible stroke.

Of the 36 deaths identified, 30 occurred during the flight.

Onboard assistance was provided by physicians in 48.1%, and nurses in 20.1% of cases.

The most commonly used medications were oxygen (49.9%), intravenous 0.9% saline solution (5.2%), and aspirin (5%).

An automated external defibrillator (AED) was applied to 137 patients (1.3%). In most cases, it was only used to monitor heart rhythm. A shock was only delivered in five cases.

The Responsibilities of Medical Professionals on Board?

When required, the cabin crew will request medical doctors or other health professionals among the passengers to come forward to assist in managing an ill passenger. Although most physicians will respond to this request, it is well known that physicians on board may not always identify themselves, most often because they believe the problem would be outside their field of practice.

The Legal Aspects

A doctor does not have a legal obligation to step forward when assistance is requested. On the other hand, the doctor has an ethical and humanitarian duty to provide emergency care, unless circumstances prevent him/her from doing so or he/she is assured that others are willing and able to give such care (11).

By responding to the in-flight call of assistance, the doctor has taken on the role of a Good Samaritan. However, good intention does not protect against gross negligence or misconduct. The key is to do the best you can in the circumstances with the resources available, working within the limits of your competence (10).

In the US, the Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998 applies when a medical professional volunteers to assist. The Samaritan is protected against malpractice litigation if the following conditions are met (4):

- The Samaritan is medically qualified to perform the service

- The Samaritan acts voluntarily

- The Samaritan acts in good faith

- The Samaritan does not engage in gross negligence or misconduct

- The Samaritan receives no monetary compensation (seat upgrades and travel vouchers do not count as compensation)

The Medical Care

Identifying yourself and specifying your level of training to the flight crew is an essential first step.

When assessing the patient, it is important to look for high-risk symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and signs of stroke such as weakness on one side of the body.

Patients with syncope are often unresponsive and hypotensive. However, in most cases, improvement occurs within 15-20 minutes. Oral or intravenous fluid administration is usually helpful.

A sensible initial step is to move the patient to an aisle or galley, place him/her in the supine position and administer oxygen. Give oral or intravenous fluids if possible.

Obtaining vital signs is important. Is the patient unconscious? Does he/she have a palpable pulse? Is he/she breathing normally? Blood pressure should be measured when possible.

When chest pain is considered to be of cardiac nature, consider administering aspirin. If systolic blood pressure is above 100 mm hg, consider administering sublingual nitroglycerin. If symptoms resolve with the above measures, aircraft diversion is not typically required.

If the patient is in cardiac arrest, perform CPR and obtain and apply an AED as soon as possible.

The Medical Resources On Board

There are legal requirements for the medical equipment that must be carried on board any commercial airplane. The standard is determined by the responsible aviation authority: the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the United States, and the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in collaboration with the Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) in Europe.

European airlines that fly to the USA must meet the requirements of both the FAA and the JAA.

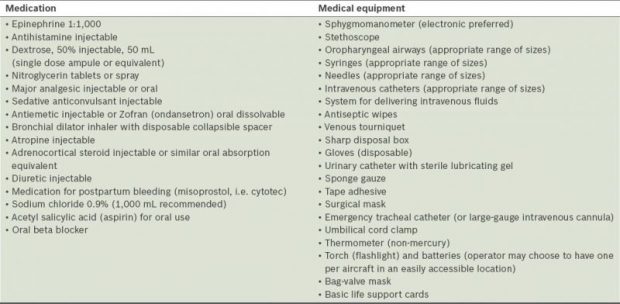

The International Civil Aviation Organization (IACO) calls for three types of medical kits; First Aid Kit (FAK), Emergency Medical Kit (EMK) and Universal Precaution Kit (UPK).

The contents of the FAK are primarily for the care of wounds and burns, but the kit may also include non-prescription medication.

Guidelines recommend that the EMK is to be used only when a medically trained doctor is available for assistance. Hence, this kit is sometimes called “the doctor’s kit”. It contains medical equipment and drugs that can be used for the clinical assessment and treatment of the passenger.

Diagnostic tools available in the EMK include a stethoscope and a sphygmomanometer. Some international aircraft have electronic blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximeters (for measurement of the oxygen saturation of blood) and glucometers (for measurements of blood glucose) in their EMK.

The UPK contains personal protection equipment for crew members and volunteer health professionals who may be exposed to communicable disease.

Most airlines also carry automated external defibrillators on board.

The Take Home Message

The majority of in-flight medical events are benign and will resolve spontaneously. Death on board is a rare occurrence.

Most events are managed by cabin crew without the assistance of an onboard health professional.

In the event of an in-flight medical emergency, a doctor is ethically obliged to help when requested. The same is true for other health professionals.

The role of the doctor is to assist and support the pilot and crew. The pilot is in command and makes the ultimate decision whether to divert the plane to another location.

The doctor should make a clinical assessment of the passenger and start necessary treatment in accordance with the resources available.

The emergency medical kit (EMK) available on board contains medical equipment and drugs that may be used for clinical examination and treatment of the passenger. The kit is to be used only when a trained medical doctor is available for assistance on the aircraft.

Most aircraft carry automatic external defibrillators (AED’s) for use in the case of cardiac arrest.

Discover more from Doc's Opinion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

That’s great to know. I actually stumbled on this question on quora https://www.quora.com/How-equipped-are-airplanes-during-a-medical-emergency-e-g-heart-attack-shortness-of-breath and there were a few answers but nothing beats this article, very comprehensive. Do you mind if I share this article as an answer there? Thanks!

Hi Tara

Sorry for the late reply. Somehow missed your comment. But thanks anyway and feel free to share the article.