Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

You can listen to this article — The Echo Chamber of Cardiology — narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

The ballroom was cold in that sterile, calculated way—air conditioning cranked just high enough to keep anyone from dozing off. Still, two rows in, a man in a navy blazer blinked slowly, arms crossed, the telltale nod of jet-lagged surrender already beginning.

The projector whirred like a tired breath.

The smell of burnt espresso drifted in from the hallway. Someone coughed. Phones buzzed on silent.

Onstage, the panelists sat in crisp formation—five experts, four logos, three institutional affiliations apiece. One click of the remote:

“LDL-C target: <70 …”

Silence. Then nods. Another click.

“Very high risk: Consider <55…”

More nods. Pens scratched. A sleeve adjusted. No questions.

There was a rhythm to it—clinical, efficient, hypnotic. The lights dimmed just enough to make the PowerPoint glow. The moderator smiled without smiling.

Everyone already knew what came next.

Behind them, sponsors leaned against the walls with folded arms, practicing neutrality. The front row was packed with gray-haired faculty and rising fellows, coats draped over chairs, faces glowing in the reflected blue light of updated guidelines. No one interrupted. No one challenged. Why would they?

The science was settled.

The targets, precise.

The language—“Class I, Level A”—offered certainty. Authority. Protection.

And yet—beneath the low hum of projectors and filtered air, something felt off.

Like a simulation of medicine, running on repeat.

A low, clinical murmur—the sound of an echo chamber.

Outside, patients were asking different questions.

“My LDL is high, but my calcium score is zero. Am I really at risk?”

“My blood pressure’s 132—do I need another pill?”

“Do all six of these meds help—or are they just wearing me down?”

Inside, those voices didn’t exist.

They weren’t on the slides.

Weren’t in the citations.

Weren’t invited.

Here, cardiology was clean.

Disease was linear.

Risk lived inside equations.

Prevention came in pills.

No need to think—just follow the flowchart.

There were no villains in the ballroom.

Just familiarity, comfort, and the slow drift of medicine into echo.

What began as evidence had become doctrine.

What was once guidance had become law.

And what passed for progress was often the same ideas, moving in circles—polished, endorsed, and sponsored.

The air smelled of espresso and industry funding.

And no one seemed to notice.

The Rise of Consensus Without Question

It didn’t happen all at once.

There was no sharp turn. No single guideline or calculator that broke the system.

The walls rose quietly—slide by slide, recommendation by recommendation.

At first, it felt like clarity.

The field aligned. Pathways got cleaner.

If you followed them, you were practicing evidence-based medicine.

If not—you’d better have a reason.

They offered safety—clinical, legal, psychological.

You could lean on them when the patient made you nervous.

Reference them when uncertain.

Feel protected, even when unsure.

And no one noticed how small the room was becoming.

The same names on the papers.

The same experts on the panels.

The trials fed the guidelines. The guidelines fed the talks. The talks reinforced the trials.

Everything reinforced everything else.

“What’s the LDL target?”

“What’s the ASCVD score?”

“What’s the A1c threshold?”

Still clinical.

But no longer curious.

Judgment became protocol and checklists. And the checklists became doctrine.

Over time, the burden of thinking shifted.

You didn’t need to ask what the patient needed.

You just followed the pathway.

When something didn’t fit, you hesitated—then clicked anyway.

The guidelines weren’t the problem.

The problem was how they became untouchable.

Deviation felt dangerous.

Skepticism, disloyal.

Disagreement made you look out of step.

So we stopped questioning.

Stopped challenging.

Stopped noticing what wasn’t being said.

Inside those walls, the field grew quiet.

That’s how medicine gets stuck.

Not from bad actors—

But from good intentions, endlessly repeated

until no one remembers how to question them.

“Medical practice is an art, not a trade; a calling, not a business;

a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.”

— Bernard Lown

The Illusion of Control

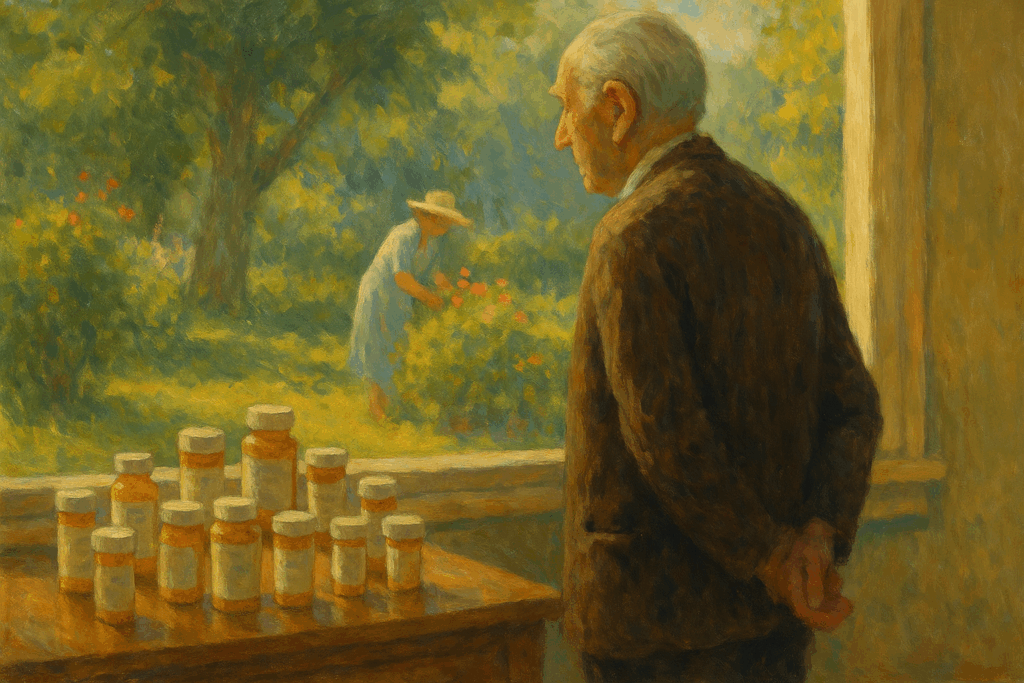

She wasn’t sick.

Not really.

She hadn’t felt unwell.

She still chased the bus when running late.

Still graded papers at night without thinking twice.

Her body felt like hers—unremarkable, reliable.

She was 52. Walked daily. Taught math.

Borderline cholesterol. Borderline blood pressure.

No diabetes. No symptoms.

But her ASCVD score came back: 7.6%.

Just over the line.

No one explained the number.

No discussion of absolute risk.

No calcium score.

Just: Start the statin.

She nodded.

Left with a prescription.

And quietly crossed a threshold—from person to patient.

We’ve grown fluent in the language of numbers.

LDL. EF. SBP. BMI.

A glance at the chart tells us what to think.

And over time, we’ve stopped thinking past it.

Her LDL-C became a verdict.

Under 100? Reassure.

Over 160? Prescribe.

Her blood pressure climbed a little—138, 142.

A new drug was added.

She came in for follow-up a year later.

Statin, check.

BP med, check.

GLP-1 added three months ago—she’d lost weight. Labs improved.

The dashboard was green, top to bottom.

Her ten-year risk? Down to 5.2%.

Everything was in range—except her life.

She wasn’t smiling.

“I feel off,” she said. “Like I’m not myself anymore.”

She moved slower. Forgot small things.

Sometimes she felt short of breath—just walking to the car.

She felt older than her age—drained in a way that didn’t show up on labs,

and unsure anyone really wanted to hear it.

I paused.

The meds were right.

The numbers proved it.

The checklist was complete.

She had an echo.

Her ejection fraction came back at 53%.

Normal. Reassuring. Within range.

So the fatigue? Probably stress.

The shortness of breath? Maybe deconditioning.

Nothing cardiac.

We told her the heart was fine—because the EF was fine.

But EF doesn’t feel fatigue.

It gives us a number—

and the illusion that we’ve understood something.

This is what happens when we confuse surrogates for outcomes.

When we mistake measurability for meaning.

We normalize LDL and assume risk has fallen.

We hit BP targets and call it prevention—

whether or not the patient feels better.

We chase numbers until they look right,

and forget to ask if the body agrees.

These aren’t decisions.

They’re reflexes.

Useful. Defensible.

But not always right.

There was a time when medicine left room for uncertainty.

Room to pause before prescribing based on a score.

Now we treat the number.

Document the compliance.

Check the box.

And move on.

The reward?

A clean chart.

A silent nod from the system.

But did we help her?

From Guidance to Governance

Guidelines were meant to help.

They started as a map—evidence distilled into direction.

A way to standardize care, reduce errors, and align decisions with data.

But somewhere along the way, the map became the terrain.

We stopped navigating.

We started obeying.

And when the map doesn’t match the patient, we adjust the patient—

not the map.

We add the statin because the ASCVD score says so.

We escalate meds because the BP is 142.

We start another drug because the A1c crosses a line.

Each decision justified.

Each number addressed.

The chart looks good.

But the patient doesn’t feel good.

And the system doesn’t notice.

Because the metrics were met.

We like to imagine guidelines as the work of a modern-day Socratic council—

physicians in careful dialogue, weighing evidence, refining the truth.

But in reality, most are assembled over email.

Tracked changes. Margin comments.

A shared Google doc. A Zoom call. A soft deadline.

A new trial slotted in. A sentence softened.

Some members show up. Others don’t.

The document moves forward—slowly.

By the time a recommendation appears in print, it’s already being cited.

By the time it’s revised, it’s already protocol.

Committees are made up of familiar names—senior academics, subspecialists, institutional lifers.

Professional societies appoint them. Some rotate. Others cycle from panel to panel.

Conflicts of interest? Disclosed—but rarely disqualifying.

The structure rewards stability over dissent.

And once a recommendation makes it in, it’s hard to take it out.

It gets embedded—

Referenced. Coded. Taught. Reimbursed.

Guidelines pile up like sediment:

Easy to add to.

Hard to revise.

Almost impossible to remove.

It’s not conspiracy.

It’s inertia.

It’s workflow.

Still, what comes out the other side behaves like law.

Recommendations become calculators.

Calculators shape treatment.

Treatment becomes audit.

Audit becomes performance.

And performance becomes medicine.

For the physician, guidelines offer something else: protection.

“I followed the guidelines.”

Not: “I thought critically.”

Not: “I knew the patient.”

So even when the patient falls, or fades, or says,

“I don’t feel like myself,”

we point to the checklist and say:

“But I did everything right.”

That’s the paradox.

The science may be sound.

But the structure we’ve built around it is not neutral.

It selects. It simplifies.

It rewards alignment.

It punishes hesitation.

And the more faithfully we follow it,

the harder it becomes to question.

Until even the most thoughtful physicians

are practicing inside a loop that no longer needs them to think.

Medicine starts to obey itself.

But what if we’re following the wrong map?

“Evidence-based medicine is not ‘cookbook’ medicine. It requires integration of best evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.”

— David Sackett

Great article and observations.

Because of the group think inside that room, I no longer trust doctors whatsoever.

14 years ago, my primary care doctor overdosed me for allergies on Kenalog and my blood pressure spiked. he sent me to a cardiologist who told me that I was about to have a heart attack and that he had to get me into the Cath Lab.

He then lied to me and told me that I had 90% blockage in my circumflex when in fact, I had 30% as evidence by angiogram review by a world class cardiologist and two other cardiologists.

While I was knocked out, he put a stent in me that I didn’t need. I sent all my records to the head of cardiology, a friend of my brother’s in a well respected NYC Hospital, & he confirmed that I had 30% blockage, not 90% and that in no way did I need a stent.

Bottom Line: you are your own best doctor and verify everything that the doctor tells you with second and third opinions.

Thanks John. You’re describing a clear breach of trust — not just a misdiagnosis, but an unnecessary invasive procedure based on false information. I can understand why that experience left you wary of doctors and medical groupthink. I think second (and even third) opinions are critical, especially when the proposed intervention carries major risks. Your story is a powerful reminder that patients must stay informed and engaged in every decision about their own care.

Thanks for the reply !!!

A VA CArdiologist, after reviewing my history & angigram was appalled. In front of me, he called a friend that used to sit in the State Medical Board & when he got off the phone, he told me to file a complaint.

When I asked if the bum that placed the stent would lose his medical licese he replied “Unfortunately No, but he might get a letter saying that a complaint had been filed.”

ALL STATE MEDICAL BOARDS SHOULD DO A BETTER JOB OF REMOVING BAD DOCTORS.

If he did this to me, how many others has he done this to.

Another note: Had I known that the bum had went to medical school in Mexico because he couldn’t get into MED school in America, I would ner have went to him.

Thank you for this most insightful post and poetry. My take as a personal opinion, not medical advice or opinion: As someone with 35 years of clinical training and practice as a GP, and 58 years of lived experience of Type One Diabetes: your written expression resonants in every chamber of my experience: too often my and other’s lived experience of chronic health conditions, the transformative learning that such conditions occasion (including that cardiologist sing from a hymnbook largely writ by pharmaceutical and food industry composers) and the desire to give something back to hopefully ease the suffering of others, is rejected, disparaged, laughed at by healthcare administrators and some clinicians. And leads to exclusion from meetings, failure to acknowledge and respond to my feedback i.e. exclusion and epistemic injustice in the face of espoused policies of inclusion and feedback. That healthcare administrators in a Commission within SA Health , Australia (one or more with conflict of interest in one particular chronic condition and its best management) would ‘protect’ and ‘excuse’ clinicians on proffered websites from answering feedback is, I contend, a convenient way to further careers at population’s and individuals’ expense – money and health-wise. In the midst of a paradigm change where training in Therapeutic Carb Reduction (TCR) is being rolled out to GPs, dietitians, diabetes educators, and dietician and medical students Aussie-wide, we find SA Health has plagiarised the unscientific and dated Aussie Dietary Guidelines of 2013 (was due for review in 2023 , now delayed until 2026) into a new food campaign (high carb low fat) unsuited to 60% of the population with metabolic syndrome and 10% with diabetes. This despite many attempts by luminaries like Dr James Muecke and others to promote TCR and being instrumental in the training and lobbying aspects of this change. And even though the Aussie Diabetes Society has published Guidelines for TCR for those with T2D – where fat and carb macros are almost diametrically opposed to the Aussie Dietary G/ls 2013 (ADGs) and supposed diet for those with diabetes), which patients are actually appraised of both and given the choice between a progressive disease and the likelihood from studies that 30 to 45% of those with T2D on TCR may achieve remission and 20% of the total stop anti-hypertensives. If you prevent metabolic syndrome from developing or advancing and even reverse it, same with T2D – how many cases of CVD might be stopped? Cardiologists here are opposed to TCR with maybe one or two exceptions) and follow the ADGs 2013’guidelines’ for diet – an organisation sponsored by Sanitarium (Seven Day Adventists). A dietary regime that is UNsuited to 70% of population mentioned above. Nevermind that the only safe way to lower a person’s serum triglycerides and raise their HDL-C is via TCR. This population are well over-represented in the risk of CVD from hypertension, inflammation, insulin resistance and glycation. Then look at paediatric dietary guidelines for diabetes e.g. ISPAD 2022 Ch 10) where TCR is banned effectively for those with T1D – despite the fact that the objections used to enable this ban have been scientifically debunked. Guidelines, still followed, that allow paediatricians to report parents for negligent, those who dare to improve the fate of their child/adolescent by trying out a low or very low carb diet. If you think following guidelines are no-one’s fault I ask you to reconsider this above example which I allege amounts to abuse – of patient, parents, family and the law. Add in the fact that some paediatricians prescribe statins to adolescents with T1D – paediatricians’ obeisance to guidelines which I allege risk the patient’s development of body and brain.

Thanks Tony. You’re saying that lived experience — even with decades of clinical practice — is often dismissed when it challenges outdated, industry-influenced guidelines. Your example of TCR shows how strong evidence can be ignored, even when it could reverse disease and reduce CVD risk. I agree — blind adherence to flawed guidelines isn’t neutral; it can cause real harm.

Someone I love has coeliac disease (self-diagnosed because they had a hunch to go gluten free. It worked, but means they haven’t done the coeliac diagnosis thing of eating gluten and being scoped. So some docs don’t believe they’re coeliac.) Well, they have problems with malabsorption, so …? They nearly died from needing thiamine replacement. Then years later it was B12. That last one means they’re now very disabled and suffering painful peripheral neuropathy from spinal cord degenaration. New guidelines don’t allow even small doses of morphine for chronic pain. They are left on Pregabalin and some codeine – indefinitely. They don’t work. They want to come off the Pregabalin as a) it causes urinary retention, and b) they already have cerebellar ataxia from the brain damage when they needed thiamine. Is Pregabalin causing more lack of balance? Should they have ever been prescribed it? Doctor doesn’t advise coming off Pregabalin, doesn’t give a time-table how to taper off it. The patient is 51, wants to try and walk again (Had no use of hands or feet for several months. Hands are returned but pain is not gone.) Physios won’t take the patient for walking until pain is managed. Is this it? Forever?