For decades, scientists have been trying to find out what causes heart disease. Although we have gained some knowledge along the way, many questions remain unanswered. Instead of providing clear answers, scientific research often raises a set of new issues that have to be addressed.

The American physicist, Thomas S. Kuhn wrote that “to be scientific is among other things to be objective and open minded” (1). Throughout history, preconceived notions and conceptual misunderstanding have restrained scientific progress and, unfortunately, continue to do so in the 21st century.

Smoking, hypertension, diabetes and high blood levels of cholesterol are examples of risk factors that have been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Modification of these factors may affect the probability of having an event such as a heart attack (myocardial infarction) or stroke.

The risk of CVD increases with age. However, most intervention trials testing the efficacy of preventive measures have focused on middle-aged individuals. This may be misleading because risk factors may vary with age. Hence, a particular risk factor may have more impact on a young individual than an older person. In theory, this might, for example, mean that high cholesterol matters more when we’re young than when we’re older.

In a very interesting paper published recently in the European Heart Journal, Gränsbo and coworkers from Malmö, Sweden address the question whether risk factor exposure in individuals differs according to age at first myocardial infarction (MI) (2). In other words, are smoking, high cholesterol, diabetes and hypertension as bad for the heart health of a 40-year-old as a 75-year- old? Of course this is a very important scientific question and the study has several strengths. It is based on a large, solid database with virtually no loss to follow-up.

Interestingly, the paper is discussed in an editorial written by Dr. Eugene Braunwald, a world renowned and highly influential U.S. cardiologist (3). Although of much less quality than Gränsbo’s paper, and pretty much off target, Barunwald’s discussion of the study findings makes for an interesting read.

Risk Factor Exposure and Age at First Myocardial Infarction

The study by Gränsbo and coworkers addresses the presence of risk factors in individuals who later develop MI early and late in life. Their analysis is based on data from a population-based registry in Malmö, Sweden. They enrolled 33.346 individuals without cardiovascular disease and who were followed for an average of 22 years.

MI developed in 3.687 patients ranging in age from 37 to 84 years, each of whom was compared with 1-2 age-matched controls who did nod develop a cardiovascular event. The main findings of this analysis were that blood levels of cholesterol and family history of MI are much stronger risk factors in younger age than in older subjects.

On the other hand, diabetes, blood triglycerides, and hypertension were equally associated with risk of MI at all ages. Body mass index was weakly associated with risk and displayed no difference with regards to age. The authors conclude that obesity-mediated risk is primarily mediated through obesity-related risk factors such as diabetes and triglyceride levels.

“Furthermore, I consider that Carthage must be destroyed”

Dr. Eugene Braunwald’s editorial addressing the study by Gränsbo and coworkers is entitled “Reduction of LDL-Cholesterol: important at all ages.” This is interesting because the study did not address LDL cholesterol at all.

Dr. Braunwald underscores the importance of considering both the relative and absolute risk when discussing the association of risk factors with age. He cites earlier findings provided by the Prospective Studies Collaboration, which combined the results of 61 prospective observational studies relating total blood cholesterol to vascular mortality in almost 900.000 subjects (4).

According to Dr. Braunwald, the results from this large database confirm that cholesterol is a much more potent risk factor for coronary heart disease in younger than older subjects. However, the incidence of CVD is much lower in the younger compared to the older age groups. Hence, much more could be gained in absolute terms by lowering cholesterol in older than younger individuals.

Dr. Braunwald believes that the implications of the Prospective Studies Collaboration’s and Gränsbo’s analysis “is that efforts to reduce total cholesterol (and its important fraction, LDL cholesterol) should be undertaken as soon as an elevation is recognized, and these efforts should be lifelong”.

However, this is not at all what Gränsbo’s paper was about. It wasn’t about LDL cholesterol and the under-use of statins. It was about how the influence of risk factors varies with age.

Why is an MI in younger patients preceded by a different risk factor pattern than an MI in older subjects? Why does the impact of cholesterol soften with time? Is it possible that the role of other factors, such as inflammation and insulin resistance increase with age? Or, are the pathological mechanisms underlying MI in the young merely different from that in the old? Dr. Braunwald’s input on those issues would have been highly appreciated. But, unfortunately, he found it more important to stick with the old cliché.

Dr. Braunwalds editorial made me think of Cato the Elder’s words: “Ceterum autem censeo Carthaginem esse delendam” “Furthermore, I consider that Carthage must be destroyed.“ This oratorical phrase was in popular use in the Roman Republic in the 2nd Century BC during the latter years of the Punic Wars against Carthage. It was frequently uttered and persistently almost to the point of absurdity by the Roman senator Cato the Elder, as a part of his speeches.”

Cholesterol and the Elderly

Dr. Braunwald believes that “In the 2013 Guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, the need for intensive therapy to reduce LDL-cholesterol for subjects older than 75 years in both primary and secondary prevention has been de-emphasized.”

He writes: “With respect, I voice my discomfort with this position on the elderly, who are the most rapidly growing segment of the population. The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) Collaboration, in a meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials, reported a significant relative risk reduction of vascular events of 16% in patients over the age of 75 years receiving statin therapy”.

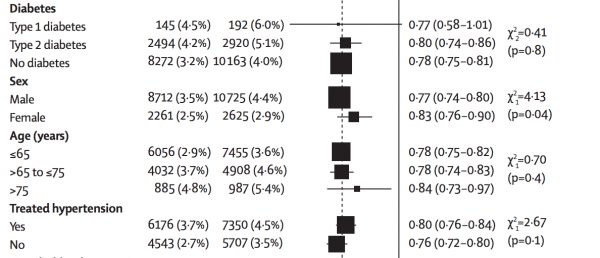

Let’s look closer at the CTT Collaboration’s study (5). Above is the data that Dr. Braunwald refers to.

Among those aged above 75, the risk of major vascular events per annum was 4.8% on statins compared with 5.4% in the control group. The relative risk reduction associated with statin therapy and a reduction of LDL cholesterol by 1.0 mmol/L is 11.1% (5.4 – 4.8/5.4 x 100), whereas the absolute risk reduction is 0.6% (5.4 – 4.8). The number needed to treat (NNT) is 167 (100/0.6). In other words, 167 individuals need to be treated for a year to prevent one major vascular event. But, importantly, no beneficial effect on mortality has been proven in this age group.

It is important to acknowledge that the above study addressed trials on primary and secondary prevention combined. In fact, the effect of statins becomes less impressive when looking solely at studies in primary prevention, e.g. patients without established cardiovascular disease.

A recent meta-analysis addressed studies on the effect of statins in elderly subjects (above age 65) without established CVD (6). The absolute risk reduction for one year was 0.34% for MI. The corresponding NNT for a year will be 294. It is important to acknowledge that the NNT was miscalculated by a factor of ten in the original publication (7).

Let’s take a closer look at the magnitude of this treatment effect. If treated with statins for a year, the probability of not having a heart attack will be increased from 98.9 percent to 99.2. percent. These numbers are hardly convincing, considering possible side effects of therapy.

Still, Dr. Braunwald concludes that “reductions of LDL cholesterol of this magnitude (1 mmol/L) can, of course, be readily obtained by intensive treatment with statins, most of which are now generic, inexpensive, and generally well tolerated. Frankly, I do not see the reason for recommending less intensive lipid-lowering therapy for the elderly, unless, of course, they have a life-threatening co-morbidity or are statin intolerant.”

Interestingly, Dr Braunwald does not mention lifestyle. Is urging doctors to prescribe statins more important than promoting a Mediterranean style diet and regular physical exercise?

Because of my deep and sincere respect for Dr. Braunwald and his achievements, it hurts to admit that I’m deeply disappointed. For me, his editorial appears off the mark, and the argumentation for more statin use among the elderly is contentious at best. It’s not all about the cholesterol anymore.

Maybe the German physicist, Max Planck was right when he said: “A new scientific truth is not usually presented in a way that convinces its opponents…; rather they gradually die of, and a rising generation is familiarized with the truth from the start.”

Discover more from Doc's Opinion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for the nice Sunday read.

You’re welcome Jan. Thanks for reading.

My distrust of doctors began 10 years ago when I was suffering from the effects of asthma. My doctor put me on a steroid inhaler (for life) and within a month I had gained a bunch of weight but I was still suffering from the effects of asthma. I ditched the inhaler and spent some time on the internet and at the library and today I no longer suffer from asthma, nor do I have the hand tremors that plagued me and my hayfever symptoms are nearly gone as well. The only change I made was to ditch the carbs, particularly wheat.

My experience made me wonder why I could spend a few days of doing my own research and enjoy great success yet a doctor whose job/career/reputation was based upon making people healthy couldn’t conceive of anything but a drug or surgery based treatment that would never be a cure and wasn’t all that effective couldn’t do the same research I did. It was then that I learned about cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias and now I at least understand why medicine, when it comes to chronic disease, has a blind spot a mile wide.

I laugh out loud when people tell me we must have healthcare for all at any cost, as if the treatment by doctors who believe that a tiny correlation drawn from observational studies is something the public desperately needs. I don’t want to sound condescending here because what you’re doing is a rarity but I congratulate you for questioning everything that you’ve held to be true in the past. It’s not often that obviously smart people will question their beliefs. We need more practitioners questioning their beliefs.

It’s difficult to understand the table when the columns aren’t labeled. I went to the paper, and it seems as if the column on the left is statin and right is control, and it seems that you cited the reverse. Clarify?

Greta.

You’re absolutely right, left is statin, right is control. I’ve corrected the sentence and it now reads: “Among those aged above 75, the risk of major vascular events per annum was 4.8% on statins compared with 5.4% in the control group.”.

Tanks for drawing my attention to it and not least for reading so thoroughly.

I’m still confused, because the RR square is to the right, indicating lower risk without the statin. Is it possible the authors got the numbers reversed?

You’re looking at the dotted line which represents the mean of all the subgroups. The other line (the undotted one) further right is the RR 1.0 line. So, the RR square is to the left of that one, meaning that stains are better than control.

Thanks. Statistics is not my strong point.

“Let’s take a closer look at the magnitude of this treatment effect. If treated with statins for a year, the probability of not having a heart attack will be increased from 98.9 to 99.2. These numbers are hardly convincing, considering possible side effects of therapy.”

Is there any reason why you chose to switch from the typical 5-year treatment interval to 1-year? NNTs are usually reported based on the former, right?

In addition, what is your alternative solution here? Treat the elderly with lifestyle intervention? Or not treat them at all?

The CTT Collaboration’s study reported the effects on major vascular effects per annum. So, I guess it was appropriate for me to deal with the primary prevention data in the same manner.

In the meta-analysis by Savarese et al, MI occurred in 2.7% of subjects allocated to receive statins compared with 3.9% of those receiving placebo during a mean follow-up of 3.5 years.

So, taking statins for 3.5 years would increase the probability of not having an MI from 96.1% to 97.3%.

Yes, you’re right. Lifestyle intervention for the elderly is the way to go. Adding a drug is not the first option in my mind. But, of course we should use statins when appropriate, and it sometimes is.

“Lifestyle intervention for the elderly is the way to go.”

What is the NNT for lifestyle intervention for people over 75?

In the PREDIMED study (Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet) the NNT to prevent an endpoint consisting of MI, stroke or death was 61 for the study period.

The upper age limit for inclusion in the study was 80 years. A subgroup analysis revealed a statistically significant positive effect of the intervention among people aged 70 or older (HR 0.71 (0.51-0.98)).

There were no reported adverse effects from the intervention.

As you may recall the authors of the paper wrote: “In conclusion, in this primary prevention trial, we observed that an energy-unrestricted Mediterranean diet, supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts, resulted in a substantial reduction in the risk of major cardiovascular events among high-risk persons. The results support the benefits of the Mediterranean diet for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.”

https://www.thennt.com/nnt/mediterranean-diet-for-heart-disease-prevention-without-known-heart-disease/

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1200303

“In the PREDIMED study (Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet) the NNT to prevent an endpoint consisting of MI, stroke or death was 61 for the study period.”

But the study period was nearly five years. I’m sure you can calculate the NNT per annum based on that – and realize it’s MUCH less than 61. And less than 167, too.

So, if it’s efficacy you’re after, Med. diet isn’t the best alternative.

How do you know that Med diet is not the best alternative?

No study has compared statins to a Med. diet in a head to head trial.

It’s difficult to compare the numbers from the PREDIMED study with the CTT Collaboration meta-analysis. The latter consists of many studies with different design, different study populations, and different results. Furthermore, most of the studies are secondary prevention trials.

The Lyon Heart study studied the effects of a Mediterranean type diet for secondary prevention.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673694925801

The NNT for preventing a repeat heart attack was 18, 30 for preventing death and 30 for preventing cancer. These numbers are pretty hard to beat.

https://www.thennt.com/nnt/mediterranean-diet-for-post-heart-attack-care/

“How do you know that Med diet is not the best alternative?”

Well, you kinda answered it yourself:

“No study has compared statins to a Med. diet in a head to head trial.”

… which is precisely why bringing up PREDIMED in this case is – at best – misleading. But it’s a good thing you realized that yourself. 🙂

“The Lyon Heart study studied the effects of a Mediterranean type diet for secondary prevention. The NNT for preventing a repeat heart attack was 18, 30 for preventing death and 30 for preventing cancer. These numbers are pretty hard to beat.”

For instance, 4S had the same NNT for death.

And bringing up the issue of cancer when talking about a trial which really wasn’t powered to study cancer prevention is … well, yet another reason why NNT.com sucks. Talk about bias.

Bottom line: if you consider Med. diet to be the best alternative for primary prevention of CHD in 75+-year-old people, where’s the evidence?

Mie. I cited the PREDIMED to answer your question about the NNT for Med. diet in people above 75. Now you tell me that bringing it up was misleading.

Then you seem to be refuting arguments that were never mine, e.g “if you consider Med. diet to be the best alternative…”. I never said that (although I might).

What I said was: “Lifestyle intervention for the elderly is the way to go. Adding a drug is not the first option in my mind. But, of course we should use statins when appropriate, and it sometimes is.”

Promoting a healthy lifestyle is my mission. You should know that by now.

Straw man! I will not participate in a pissing contest. Have a great day. 🙂

“Mie. I cited the PREDIMED to answer your question about the NNT for Med. diet in people above 75. Now you tell me that bringing it up was misleading.”

It was, provided that you’re suggesting it as a better alternative for statins. Hey, you yourself stated WHY!! More about this below.

“Then you seem to be refuting arguments that were never mine, e.g “if you consider Med. diet to be the best alternative…”. I never said that (although I might).”

C’mon Axel, don’t try to backpedal.

1) You rejected statins for the elderly.

2) Naturally, that suggests that there is a SUPERIOR alternative (as you’re always supposed to offer the best possible care). I asked what’s your choice then, and you answered (quoting you here):

“Lifestyle intervention for the elderly is the way to go”

3) Next, I wanted to know the NNT for lifestyle intervention. Then YOU brought up Med. diet. Now, the BEST possible interpretation for this is that Med. diet is precisely the superior alternative for lifestyle intervention!

However, if it isn’t, then feel free the tell what’s the best solution. “Lifestyle intervention” is an umbrella term that encompasses a lot. So c’mon, share the wisdom: what’s the NNT for lifestyle intervention – whatever the type that produces the best results!

P.S. Don’t use terms like straw man if you don’t know what they mean.

Thought I’d clarify this

“1) You rejected statins for the elderly.”

before you go and misinterpret it. That is, you rejected statins as the PRIMARY option, though not for everyone and/or as a secondary choice is lifestyle intervention fails.

However, that doesn’t change the original question: what is the NNT for lifestyle intervention. What is the scientific basis for your claim that is is “the way to go”?

As you know, RCT’s on lifestyle intervention are much more difficult to perform than drug intervention studies – and obviously sponsors are more difficult to find (Big Pharma not interested of course).

But there certainly is data, both from observational studies and RCT’s.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23867029

The meta-analysis showed a significant advantage for patients undergoing multifactorial lifestyle interventions with respect to fatal cardiovascular events with an estimated risk reduction of 18% (RR 0.82, 95% CI=0.69, 0.98; p=0.03).

Go on, calculate the NNT. If you know what a Straw man is you should be able to do that.

Did you know that you don’t have to choose between healthy lifestyle and statins? In fact, you can choose both. However, healthy lifestyle is always appropriate, statins only occasionally.

“Go on, calculate the NNT.”

I can’t do it, unless I can get info on ARR – and I can’t access the full text. If you can, please: make your point.

In addition, remember that we’re talking about 75+-year-olds here. If the review included a subgroup analysis, you’d have to use that to calculate the NNT.

“However, healthy lifestyle is always appropriate, statins only occasionally.”

When talking about disease prevention in general, yes. A healthy lifestyle can do far more good than statins if you can keep it up.

But we’re not talking about that, as you well know.

Among those aged above 75, the risk of major vascular events per annum was 4.8% on statins compared with 5.4% in the control group.

Say no more. This study is pure BS. And sadly, most Americans thing that a “16% decline” means going from 20% chance to a 4% chance. Big Pharma loves this. And I wonder if this so-called “doctor” is on some Big Pharma advisory board.

Very usefull for me.

Have you seen this study?

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/6/e010401.abstract

Lack of an association or an inverse association between low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality in the elderly: a systematic review

Conclusions High LDL-C is inversely associated with mortality in most people over 60 years. This finding is inconsistent with the cholesterol hypothesis (ie, that cholesterol, particularly LDL-C, is inherently atherogenic). Since elderly people with high LDL-C live as long or longer than those with low LDL-C, our analysis provides reason to question the validity of the cholesterol hypothesis. Moreover, our study provides the rationale for a re-evaluation of guidelines recommending pharmacological reduction of LDL-C in the elderly as a component of cardiovascular disease prevention strategies.

Hi Axel,

I’ve read almost all your posts and want to say thank you for all the great articles. So nice that you are seeking the truth rather than trying to prove a philosophical or monetary agenda. Your analysis’ are great. For example, by reading the first part, I was thinking a 15-20% risk reduction sounds good. The further analysis showed the absolute risk reduction is 1.5%, which is pretty small. Statistics can be tricky for the uninformrd. Combining that with the total mortality results and high monetary cost, I think I’ll just keep following your eating advice and my exercise program.

Thanks Andy.

Appreciate your interest.