Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, “The Statin Empire”, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

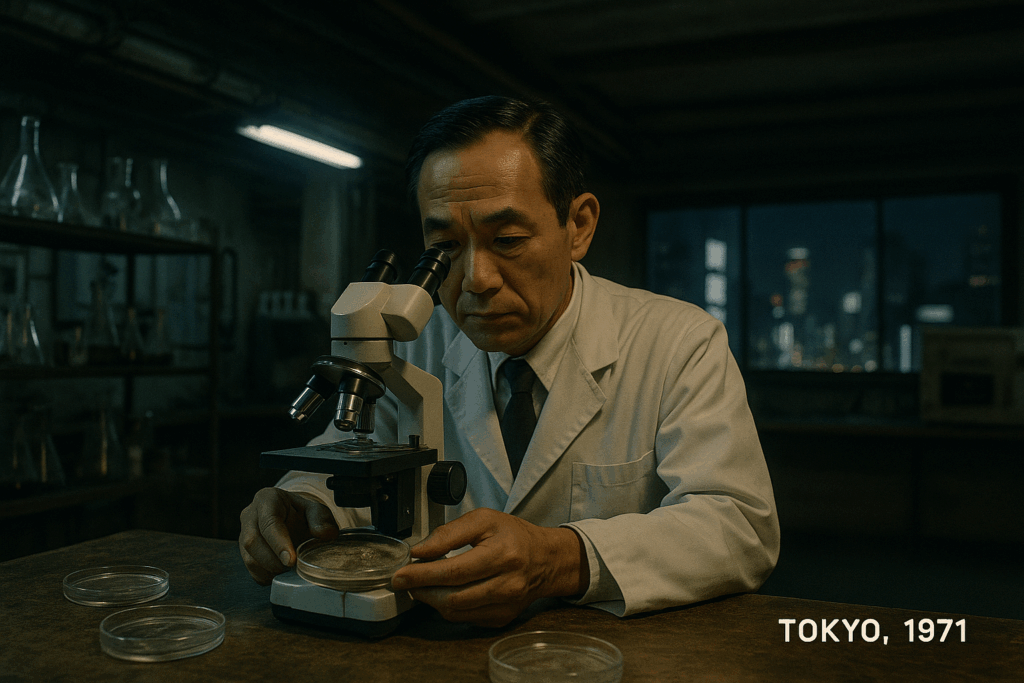

Tokyo, 1971.

A basement humming beneath the city.

Pipes ticking. The faint smell of yeast and metal.

Akira Endo sat over a tray of fungal cultures, listening to their chemical mutterings the way some people listen to the sea.

He wasn’t chasing infection.

He was trying to interrupt a rhythm inside the human body so ancient it felt untouchable.

The enzyme — HMG-CoA reductase — pulsed like a quiet metronome.

If he could soften that pulse, maybe cholesterol production would ease.

A gentle, molecular hand on the brake.

Most colleagues glanced at his findings with polite confusion.

Cholesterol was part of the cell’s scaffolding.

Interfering with it felt like leaning too hard on a load-bearing wall.

But Endo kept going.

Kept listening.

Kept trusting that the fungus held a whisper worth hearing.

In a dish of Penicillium, the enzyme flickered.

Then it went still.

Compactin.

A molecule with promise — and consequences no one could yet imagine.

Across the Pacific, in a fluorescent Merck laboratory, chemists pored over Endo’s data like investigators examining a blurred photograph.

Compactin wasn’t the discovery.

It was the blueprint.

They built their own version — lovastatin — colder, cleaner, easier to manufacture.

Not theft.

Not conspiracy.

Just momentum.

Science following a scent.

When lovastatin reached the FDA in 1987, prevention stepped onto a new slope.

A pill for risk — not for disease.

A pill for people who felt well.

And almost no one paused to absorb what that shift implied.

Statins spread the way new protocols do: quietly, confidently, impersonally.

LDL-C became a compass.

Charts gained new color codes.

Patients learned to fear numbers they hadn’t known ten years earlier.

Then came the 4S trial — the one that changed everything.

Simvastatin lowered mortality in people with established disease.

Not surrogate success.

Not theoretical benefit.

Actual survival.

The pipeline lit green.

Lives were saved.

That mattered.

It still does.

But clarity casts shadows.

Success gathers momentum.

And momentum, if left unchecked, erases nuance.

LDL-C — a partial marker of a complex process — began standing in for the entire process itself.

Lower became better.

Better became necessary.

Necessary became moral.

Then Pfizer entered the story.

Late to the scene but armed with atorvastatin — a molecule that could flatten LDL-C curves with theatrical ease.

Pfizer didn’t claim it cured disease.

They didn’t need to.

They had the curve.

And in that era, the curve was enough.

Lipitor arrived in 1997 with relentless precision.

Not sinister — just disciplined.

A military-grade rollout wearing a stethoscope.

Doctors adjusted.

Patients complied.

Pharmacies filled millions of scripts.

Outcomes would come later.

The market didn’t wait.

Yet even strong systems develop fractures.

A woman on simvastatin whose thighs burned for the first time in 40 years.

A marathon runner on atorvastatin who couldn’t climb a hill he’d run since college.

A teacher whose memory dimmed like a room with the lights turned low.

Doctors reassured.

Sometimes they were right.

Sometimes not.

Not because statins failed —

but because medicine underestimated human variability, the messy spectrum between tolerance and intolerance, risk and resilience.

And because large trials rarely match the texture of everyday life.

By the mid-2000s, the unease settled in.

Primary prevention trials showed modest absolute benefit.

NNTs drifted upward.

People with no plaque were medicated for decades.

CT scanners, humming quietly in radiology suites, revealed arteries that didn’t obey LDL rules.

Some patients with LDL 190 had clean coronaries.

Some with LDL 130 carried silent scars.

LDL-C was part of the story — never the whole of it.

And anyone who spent enough nights on the cardiology wards eventually saw the mismatch firsthand.

The Night Ward

Just after 2 a.m.

Lights dimmed to half-strength.

The kind of hospital quiet that makes every thought land with more weight than it deserves.

A cardiology fellow stood in the CT reading room, scrubs still marked from the case he’d just finished. Barely an hour earlier, he’d been in the cath lab helping open the LAD of a 45-year-old man in the middle of a STEMI — a man whose LDL-C was 105.

Ordinary.

Unremarkable.

Nothing that hinted at the artery he’d just seen torn open on the monitor.

That case followed him into the reading room like a question that refused to lie still.

He should have been asleep by now.

Instead, he stared at two images on the screen, side by side, as if the hospital itself had arranged them for comparison.

Left: the lipid panel of a 58-year-old admitted for atypical chest discomfort.

LDL-C: 195 mg/dL.

A number that practically shouted.

Right: his imaging — first the coronary calcium scan.

Zero.

A perfect zero.

Not a fleck of calcification anywhere.

Then the CT coronary angiography.

Clean.

Utterly clean.

No soft plaque.

No hidden lesions waiting in the shadows.

Arteries as smooth and bright as polished glass.

He zoomed through each vessel — LAD, RCA, circumflex — searching for anything he might have missed.

A speck.

A smudge.

A hint that the number knew what it was talking about.

There was nothing.

Behind him, a monitor chirped twice and fell silent.

Footsteps drifted down the hallway.

Somewhere, a nurse laughed softly before remembering the hour.

Two men.

Same night.

Same hospital.

Numbers pointing in opposite directions — and both of them wrong.

One nearly died with an LDL-C that would never have raised a guideline’s eyebrow.

The other, with an LDL-C of 195, carried arteries as pristine as a brand-new textbook.

In medical school, they had taught him that numbers don’t lie.

Tonight, the numbers felt like they were whispering through clenched teeth —

speaking in halves, withholding the rest.

He printed the report, folded it twice, and slipped it into his pocket.

A contradiction he wasn’t ready to resolve.

A question he knew he would carry for years.

He wasn’t the only one beginning to see the cracks.

If you enjoy DocsOpinion’s articles, you may also like my Substack newsletter — shorter reflections, serialized essays, and behind-the-scenes notes on medicine, history, and science.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Interesting, though a bit of dancing around without really spelling out the essential: how does one determine if the statin was built for him. Is it a non zero calcium score, what other biomarkers???

Great question — and you’re right to ask for something concrete.

A statin is “built for you” if there is documented atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

The evidence is much less clear in primary prevention.

However, statins may be considered when your arteries or your biology show signs of atherosclerotic risk, not just your LDL-C level.

The strongest predictors that someone will benefit from a statin are:

Non-zero coronary calcium score.

Elevated ApoB or non-HDL-C (better markers atherogenic of particle burden)

Evidence of plaque on coronary CT angiography

Diabetes, where atherosclerosis risk is intrinsically higher

Strong family history or genetic risk (FH, Lp(a))

When CAC is zero, ApoB is modest, and no plaque is present, the absolute benefit becomes very small — especially in middle-aged patients.

That’s where “the drift” happened: we treated the number instead of the person.

64 yr old non smoking female. My Apo b is 87, Lipo a is 13, LDL 125, CAC zero, CT cardiac with contrast no plaque, no stenosis, but one older sister died from heart attack and another just needed a stent. Would a statin be prudent for me? I had decided the side effects outweighed the benefit, but maybe not because of family history.

Interesting as always thanks. With the two people illustrated, I do wonder about the temporality aspect though. Perhaps the guy with 105 LDL-C had another comorbidity that is known to lower cholesterol (liver disease, kidney disease, cancer and quite a few more – ie reverse causality). Similarly the guy with 195 may have relatively recently reached those levels due to a change in diet and had decades of low cholesterol.

What you’re describing is certainly possible. But the point I was making there was different—and real. The examples were meant to show that LDL-C by itself does not reliably capture individual risk, even without invoking reverse causality or recent changes in exposure.

Temporality and comorbidity add important nuance, but they don’t resolve the core issue: people with similar LDL numbers can have very different plaque biology, particle burden, and clinical trajectories. That limitation of LDL-centric thinking was the phenomenon being illustrated.

I’m a 71 year old male with LDL 276, HDL 51 and Total Cholesterol of 355. Calculated apo-b of 202. My CAC score three years ago was an LAD of 30. Father passed at 71 from MI. Just started on 5 mg of Crestor generic, thinking that i am a good candidate. Your thoughts?

Get your Lpa tested as well. I would up the Crestor for sure