Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Zinc deficiency has been associated with an increased risk of upper respiratory tract infections. Furthermore, evidence suggests that severe zinc deficiency depresses immune function.

Consequently, a potential medical role of zinc for the treatment of Covid-19 has been highlighted. Currently, however, there is no evidence that taking zinc will protect against Covid-19 or make the disease milder. Nevertheless, epitomizing the role of zinc for the human body is certainly worthwhile.

Zinc is defined as a trace mineral as the body only needs very small amounts to satisfy its requirements. It is an essential mineral for microorganisms, plants, and animals. Zinc plays numerous roles in the human body and is necessary for many enzymes that are essential for vital chemical reactions.

Compared to adults, infants, children, adolescents, pregnant, and lactating women have increased requirements for zinc (1).

Zinc deficiency is one of the most important micronutrient deficiencies on a global scale. However, it is relatively uncommon in the US and other Western countries.

Although consuming more than the recommended daily amount has not been proven beneficial for most people, several studies show that supplementing high-risk populations can have substantial health benefits (2).

Be aware, however, that consuming high doses may cause zinc toxicity.

Critical Issues in Zinc Metabolism

Zinc is released from food as free ions during digestion. It is primarily absorbed in the small intestine. About 70% of the zinc in the circulation is bound to a common transport protein called albumin (1).

Zinc is present in all body tissues and fluids in the human body.

Maintaining a constant state of cellular zinc is essential for health. The body mainly controls its levels by adjustments in intestinal absorption and excretion (3).

Approximately half of all zinc is eliminated through the gastrointestinal tract. Other routes include urine excretion and surface losses (skin, hair, sweat) (4).

The Role of Zinc in the Human Body

Zinc plays an important for maintaining the structure of numerous vital proteins in the human body. Approximately 250 of the body’s proteins contain zinc (2).

Many of these proteins are enzymes that participate in the synthesis and degradation of carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, as well as in the metabolism of other micronutrients (5).

Zinc is needed for healthy growth. It plays a vital role in immune function, wound healing, blood clotting, thyroid function, and much more.

Zinc-containing proteins play an essential role in the molecular structure of cellular components and membranes. Hence, zinc plays a crucial role in the maintenance of cell integrity.

Zinc plays an essential role in maintaining vision, and it is present in high concentrations in the eye. Deficiency can alter vision and, when severe, can cause changes in the retina.

The Dietary Sources

A wide variety of foods contain zinc. Meat, chicken, nuts, oats, seeds, and lentils are excellent sources and so is milk and cheese (2, 7)

Oysters contain more zinc per serving than any other food (8). Other types of seafood, such as crab and lobsters, are also good sources.

In the Western diet, food products such as breakfast cereal are often fortified with zinc.

In the US, pulses and cereals provide about 30% of dietary zinc, meat about 50%, and dairy products about 20% (9). Usually, pulses, contain more amount than refined cereals.

Most cooking oils, sugar, and alcohol have very low zinc content.

How Much Should We Consume?

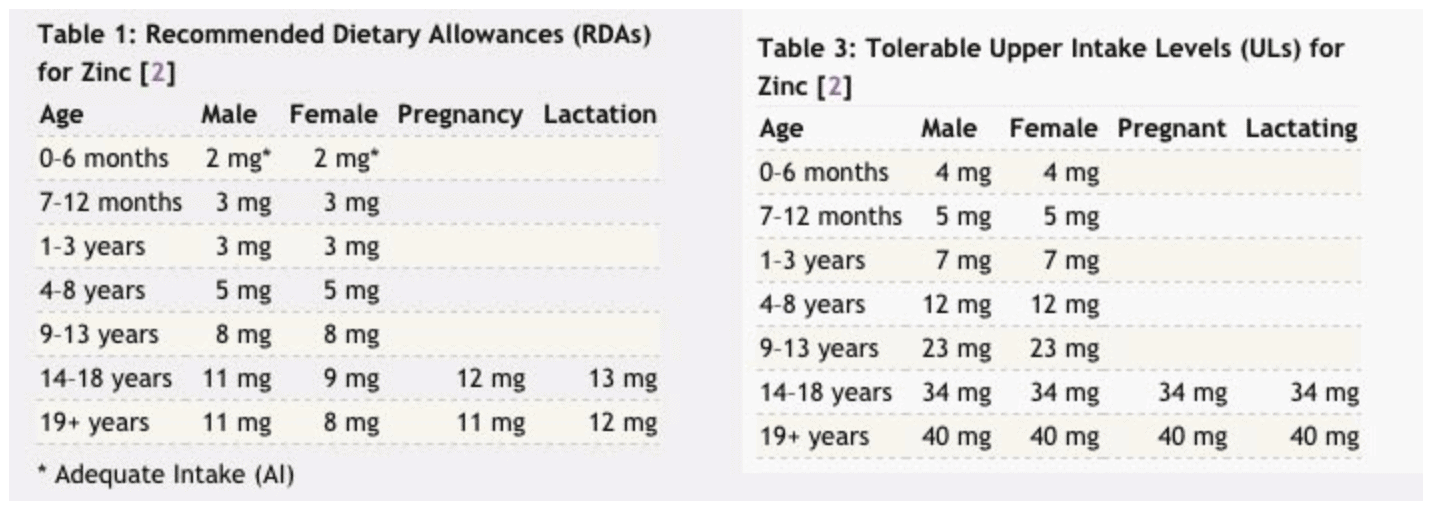

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is the average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of the majority of healthy individuals.

The tolerable upper intake level (UL) is the highest level of a daily nutrient intake that will most likely present no risk of adverse health effects in almost all individuals in the general population.

The table below shows the RDA and UL for Zinc (6).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends 11 mg/day of zinc for men and 8 mg/day for women.

Zinc is probably save for most adults when taken by mouth in amounts not larger than 40 mg daily. Hence, if you are taking supplements, be careful not to consume higher doses.

High doses above the recommended amounts might cause fever, coughing, stomach pain, fatigue, and many other problems.

A few studies have suggested that high doses (more than 100 mg/day) may increase the risk of advanced prostate cancer(10).

Zinc Deficiency

Inadequate dietary intake of absorbable zinc is the most common cause of deficiency.

Zinc intake is closely related to protein intake; as a result, zinc deficiency is an important component of nutritionally related morbidity worldwide (11).

Conservative estimates suggest that 25% of the world’s population is at risk of zinc deficiency (12).

Zinc deficiency is most common among the poor because of the lack of foods rich in highly bioavailable zinc. Animal foods that often are rich sources are often not easily accessible to people living in low-income countries. Furthermore, diets based on cereals and legumes and poor in animal products may promote deficiency due to their high phytate content, which may reduce the bioavailability of zinc.

Symptoms attributable to severe zinc depletion include growth failure, delayed sexual and bone maturation, skin disease, diarrhea, impaired appetite, taste and smell, night blindness, delayed wound healing, and impaired immunity and resistance to infection.

In early infancy, diarrhea is a common symptom of zinc deficiency. Skin problems often become prominent as the child grows older. Impaired cognition, behavioral issues, and learning disabilities may also occur (1).

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare inherited form of zinc deficiency, characterized by skin changes, alopecia, and diarrhea. It is caused by malabsorption of zinc from the small intestine. Treatment of the disorder requires lifelong supplementation (13).

Groups at Risk for Zinc Deficiency

Zinc requirements are increased during growth. Hence, young children are at higher risk of deficiency.

Infants usually receive sufficient amounts during breastfeeding. After that, zinc-containing foods are required to satisfy the requirements (1).

The body’s requirements for zinc peak during adolescence. Adolescents may be sensitive to deficiency during the pubertal growth spurt. Even after the growth spurt has ceased, adolescents may require additional zinc to replenish depleted tissue pools (11).

Pregnant and lactating women are at risk of deficiency due to increased nutritional demands (14).

Zinc intake is often inadequate in elderly persons. Also, there is some evidence that the efficiency of absorption may decrease with age. However, zinc deficiency seems to be relatively rare in healthy free-living late middle-age and older subjects (15).

The bioavailability of zinc from vegetarian diets is lower than from non-vegetarian diets, mostly due to the the lack of meat. Besides, vegetarians often consume high amounts of legumes and whole grains, which contain phytate that binds zinc and inhibits its absorption from the gastrointestinal tract (6).

Vegetarians can decrease the risk of zinc deficiency by soaking beans, grains, and seeds in water for several hours before cooking them and allowing them to sit after soaking until sprouts form (16).

Vegetarians can also increase their zinc intake by consuming more leavened grain products (such as bread) than unleavened products (such as crackers) because leavening partially breaks down the phytate; thus, the body absorbs more zinc from leavened grains than unleavened grains (6).

Approximately 30%–50% of alcoholics have low zinc status because ethanol consumption decreases intestinal zinc absorption and increases urinary excretion. Moreover, the variety of food consumed by many alcoholics is limited, leading to inadequate zinc intake.

Zinc in Health and Disease

Severe zinc deficiency depresses immune function (17). This may explain why deficiency has been associated with an increased risk of pneumonia and other infections.

Zinc helps maintain the integrity of skin and mucosal membranes (18). Hence, clinicians often treat skin ulcers with topical zinc supplements.

Studies have shown that zinc supplements may be used to treat diarrhea in poor malnourished children (19). However, the effects of supplementation on diarrhea in children with adequate zinc status, such as most children in the US and other Western countries, is unclear.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of vision loss for people age 50 and older.

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS), showed that individuals at high risk for AMD could slow the progression of advanced AMD by about 25 percent and visual acuity loss by 19 percent by taking 40-80 mg/day of zinc, along with certain antioxidants (vitamin C, vitamin E, copper, lutein, zeaxanthin).

Taking higher levels of zinc may interfere with copper absorption, which is why a copper supplement was also included in AREDS (20).

Taking zinc improves symptoms of an inherited disorder called Wilson disease. Patients with Wilson disease have too much copper in their bodies (21).

Zinc for the Common Cold

It has been suggested that zinc could reduce the severity and duration of the common cold. However, clinical studies on the issue have shown conflicting results. There is evidence that zinc may reduce the binding of rhinovirus to the nasal mucosa, thereby suppressing the inflammatory response.

One study showed that the administration of zinc lozenges was associated with reduced duration and severity of cold symptoms (22).

Another clinical trial found that zinc gluconate lozenges significantly reduce the duration of symptoms in subjects with experimental rhinovirus colds (23). However, the severity of symptoms was not affected.

Neither zinc gluconate nor zinc acetate lozenges affected the duration or severity of cold symptoms in subjects with natural cold (24).

A recent Cochrane review concluded that zinc (lozenges or syrup) administered within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms reduces the duration and severity of the common cold in healthy people (25).

The Cochrane review also points out that there is potential for zinc lozenges to produce side effects. Due to somewhat conflicting data, it is difficult to make firm recommendations about the dose, formulation, and duration that should be used.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a public health advisory advising that over-the-counter zinc-containing nasal products (Zicam) should not be used because of multiple reports of permanent anosmia (absent or decreased sense of smell) (26).

Zinc is also available in a homeopathic preparation as intranasal zinc gluconate for the treatment and prevention of colds. This formulation has also been found to cause anosmia (27)

Supplements: Dosing, Risks, and Benefits

Zinc is available as a dietary supplement. It is also present in many cold lozenges and some over-the-counter drugs sold as cold remedies.

Most people will not benefit from oral zinc supplements if their zinc status is normal.

However, there is an enormous potential for reducing the burden of zinc deficiency with targeted supplementation in both developed and developing countries (28).

Zinc supplements are most likely to be helpful if other potentially limiting micronutrients are administered simultaneously (29).

Zinc toxicity can occur in both acute and chronic forms. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and diarrhea may occur. Headache is also common.

Large doses of zinc may cause copper deficiency, hence if supplements are consumed, the amounts of zinc and copper should be proportionate.

Zinc has two standard dosages. The low dosage, 5-10 mg daily, works well as a daily preventative. The high dosage, 25-45mg, should only be taken by individuals at risk for a zinc deficiency or if there is a proven medical benefit.

Several forms of supplements are available (30):

- Zinc citrate is approximately 34% zinc by weight. (146 mg of zinc citrate contains 50 mg of elemental zinc)

- Zinc sulfate is approximately 22% zinc by weight (220 mg of zinc sulfate contain 50 mg of elemental zinc)

- Zinc gluconate is approximately 13% zinc by weight (385 mg of zinc gluconate contain 5o mg of elemental zinc)

- Zinc monomethionine is approximately 21% zinc by weight (238 mg of zinc monomethionine contain 50 mg of elemental zinc)

Soil mineral deficiencies make it much more difficult to obtain the vital nutrition we need from our food. Soils worldwide are chronically depleted and we need to consume far more food to reach healthy levels.

Hi, Axel,

You really created a useful article on zinc and provided plenty of ways to get it into your diet.

I thought the most interesting part of the post was mentioning that zinc is less bioavailable in a vegetarian diet. That’s why it’s so important for people to speak to a healthcare provider before they make any lifestyle changes. They are the ones who can let you know what kinds of supplements to take to thrive.