Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, “Why So Many Men Feel ‘Off’ at Fifty — And Say Nothing”, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

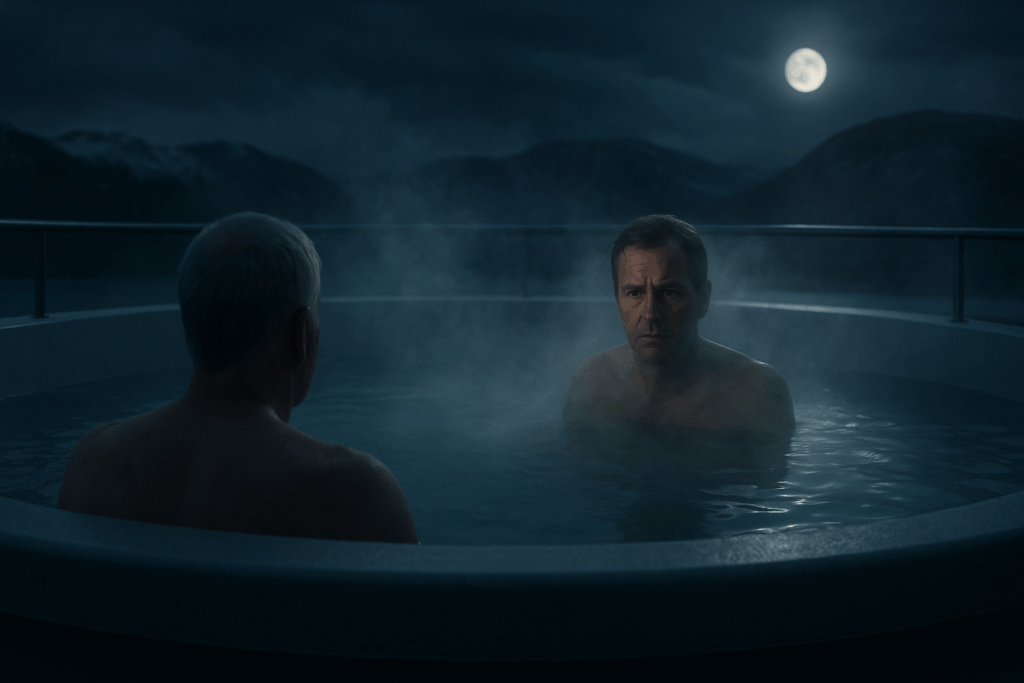

The outdoor pool was almost empty — the way it gets when the cold drops straight from Esja and cuts across the water. Steam drifted in uneven waves, rising, folding, breaking apart again.

He stepped into the hot tub quietly, shoulders held a little too firmly. No sigh, no settling back — just a controlled descent.

He sat across from me, hand on thighs, water to his collarbones. His eyes moved over the deck the way people look when they’re not really seeing anything.

After a moment, he looked over.

“Cold evening,” he said. A safe line.

“Colder than it looks,” I answered.

He gave a short breath through his nose.

“Good night for hot water.”

“Always.”

The pause that followed was comfortable, but it had tension in it. Steam moved across his face like a veil — revealing, softening, revealing again. His eyes kept drifting toward the darker corner of the deck where the light didn’t quite reach.

“Long day?” I asked.

“Yeah. Just… full.”

A small word carrying something heavier.

He lifted a hand and pressed it briefly to the center of his chest — not checking, just steadying himself. The gesture vanished almost before it happened.

“You doing alright?”

“Sure. Just been feeling… tight. Comes and goes.”

He tapped his chest once, without noticing.

Nothing dramatic. Nothing you’d document.

But the way he kept scanning the shadows told its own story.

For a moment, the steam split, and he sat there clearly — a man in warm water, holding something unspoken.

Then the steam closed again.

He didn’t look at me. He didn’t need to.

Some things announce themselves quietly, long before the man finds language for them.

And watching him, I had the sense his ground had already begun to shift. You only realize how much later.

From the Steam to the Story

Men like him are everywhere — carrying tension, minimizing symptoms, telling themselves they’re fine. Their stories rarely begin with crisis. They begin the way he entered the water: quietly, controlled, already bracing.

Ask how they feel, and they give you facts.

Ask again and you get work, sleep, stress — practical things, none of which explain the drift in their eyes.

But wait long enough, and the real story appears in the small details.

This isn’t about cholesterol or blood pressure or even early coronary disease.

It’s something subtler: a slow drift away from themselves.

It has physiology.

It has patterns.

And it begins long before symptoms do.

The Quiet Storm Inside the Middle-Aged Body

There’s a moment in midlife — earlier than most expect — when the body stops speaking clearly. Not pain. Not illness. Just a sense that things don’t run as smoothly as before.

Around fifty, most men experience a private realization: youth isn’t coming back.

They feel it before they admit it.

At the same time, the nervous system shifts. Sleep lightens. Recovery shrinks. Stress sits closer to the surface. The capacity is still there, but the margins are narrowing.

If you measured it, you’d see the signs:

- nighttime blood pressure not dipping

- heart rate variability (HRV) drifting down

- cortisol flattening

- glucose settling more slowly

But men don’t measure these things. They judge the day by whether anything hurts. And at fifty, nothing hurts — it simply feels off.

A faint tightness under the sternum.

A breath that feels shorter on the stairs.

Morning stiffness that once belonged to older men.

Meanwhile, silent changes accumulate: vascular stiffness, creeping visceral fat, low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance.

It isn’t aging.

It’s load carried for years without release.

Most men know, in a distant way, that they’re postponing the inevitable reckoning. But as long as the body doesn’t shout, they wait.

And early heart disease never shouts.

The Disappearing Friendships

Watch fifty-year-old men, and another pattern appears: their friendships thin out.

Not from conflict.

Not from intention.

Just erosion.

In their twenties, friends were part of life.

In their thirties, scheduled.

By fifty, they’re memories managed through group chats nobody answers.

Men don’t call this loneliness.

They call it “being busy.”

And loneliness in men rarely looks emotional.

It looks like staying late at the office.

It looks like eating with a glowing screen.

It looks like silence that has gone on too long.

But the body knows.

Social thinning has physiological fingerprints —

a nervous system running slightly hotter,

slower recovery,

restless sleep,

blood pressure drifting upward almost imperceptibly.

And here is the uncomfortable truth: loneliness is not metaphorical.

It is a cardiovascular risk factor.

The research is clear —

chronic social isolation increases inflammation,

raises stress hormones,

alters autonomic balance,

and carries a risk comparable to smoking or obesity.

Men often assume loneliness means having no one.

But the most common form is quieter: being surrounded by people and still feeling unseen.

You can have a partner, children, colleagues —

and still feel stripped of the kind of connection that ventilates your internal world.

Loneliness is not the absence of people.

It’s the absence of being known.

Many men at fifty carry Type D traits — not pathology, just inwardness, inhibition, the habit of containing stress rather than sharing it. Over time, silence becomes their default setting. And silence has weight.

This is why a man can sit in a hot tub on a cold evening, life stable on paper, and still feel slightly unsteady in his own chest.

Something essential has thinned.

And the body responds long before he does.

The Fear Men Don’t Name

Fear in midlife seldom arrives dramatically.

It shows up in fragments:

A breath held too long.

A pause on the stairs.

A sensation in the chest that disappears before he decides what it was.

Men explain these moments away — coffee, stress, fatigue.

But something fundamental has shifted: the body no longer feels entirely predictable.

Fear often appears at night.

The 3 a.m. awakening — not panic, just a sharp awareness that doesn’t feel normal.

By morning, life continues.

But the nervous system remembers.

Men start monitoring themselves: heart rate on gentle inclines, breathing while carrying groceries, pulse at rest.

They never say, “I’m worried.”

They say, “It’s probably nothing.”

But the body has been carrying the fear for months, sometimes years.

Midlife is when men first understand that the body is not a promise — it’s a contract.

And the terms have changed.

The System Doesn’t Make This Easy

Clinics are built for clarity.

Stories like these are not.

Once a man sits in an exam room, he edits himself automatically.

Symptoms. Duration. Better or worse.

There’s no box for “I feel wrong, but I can’t explain why.”

So he trims his story until it sounds medical.

“I’m probably fine.”

And the system often confirms it:

normal ECG

normal clinic blood pressure

normal blood tests

Normal on paper — while the man knows something isn’t right.

He leaves reassured but not relieved.

And because nothing dramatic is happening, he waits.

Men wait for unmistakable symptoms — the kind no one can ignore.

But heart disease rarely begins with unmistakable symptoms.

It begins with unease — the exact thing men are trained to dismiss.

The system isn’t failing them.

It simply wasn’t built for the gray zone where most middle-aged men actually live.

And in that gray zone, early signals fade until the body forces a reckoning.

What Actually Helps

Change begins smaller than men expect.

A walk after dinner.

A message sent instead of postponed.

A conversation that doesn’t need to solve anything.

Connection doesn’t require depth — only presence.

It’s the steady background of other people that keeps the nervous system from running too hot. A five-minute chat. A shared laugh. A nod from someone who knows you. A brief hand on your shoulder. Even a warm smile from someone you trust. Small signals, barely noticeable, but the body registers them instantly.

Men underestimate how much these tiny contacts matter. But the physiology doesn’t. It settles as soon as it senses the load is not being carried alone.

The body responds quickly:

breathing slows, sleep deepens, the nervous system drops half a gear.

Then come the basics — dull but decisive:

movement, steadier routines, fewer screens at night, food that brings calm instead of chaos.

Not perfection.

Just consistency.

Alcohol — the evening loosener — complicates things.

It relaxes briefly, then steals sleep, raises nighttime blood pressure, and tightens the next morning.

It feels like relief.

It rarely is.

Then comes information — the kind that reduces uncertainty in a simple, practical way. A basic medical checkup.

A chance to see how things are actually running rather than guessing from how they feel. Not a search for dramatic findings, just a clearer view of blood pressure, metabolism, recovery, and the small trends that often go unnoticed.

That clarity can be unsettling.

But uncertainty is heavier.

It keeps men imagining problems instead of understanding their situation.

Once you stop guessing and start looking — even at the basics — the nervous system settles.

The next step becomes something real, not something feared.

The deeper shift occurs when a man gives himself permission to take his own unease seriously — without waiting for a crisis to legitimize it.

Most men don’t need a new identity.

They need space — to rest, breathe, and acknowledge what they’ve been carrying quietly for too long.

Often the first sign of improvement isn’t a number.

It’s an exhale that isn’t braced.

The body improves before the mind believes it.

The Night the Water Went Still

A few weeks after that cold evening, I saw him again.

Same pool.

Same hour.

Steam rising in slow columns before the wind folded it back.

This time he wasn’t alone.

Another man sat beside him — someone he didn’t need to perform for. Their conversation was soft, ordinary, unforced.

He looked different. Not transformed — just more present.

His shoulders had lowered.

His breath carried weight again.

His eyes stayed where his thoughts were, not drifting to the shadows.

He leaned back for a moment, arms floating, eyes briefly closed.

A small thing. But unmistakably ease.

He noticed me and nodded. Same gesture as before, but not the same man.

Maybe he talked to someone.

Maybe he slept.

Maybe he saw a number that gave him clarity instead of dread.

Or maybe nothing dramatic changed.

Sometimes the body settles when a man stops fighting himself.

Sometimes tension loosens when silence breaks — even a little.

As he walked toward the gate, towel over his shoulders, steam trailing behind him, he moved with a steadiness I hadn’t seen before.

And watching him disappear into the cold reminded me of something medicine rarely says out loud:

It isn’t always the artery that needs attention.

More often, it’s the man.

The quiet storm inside middle-aged men is real.

So is the calm that comes when they stop carrying it alone.

If you enjoy DocsOpinion’s articles, you may also like my Substack newsletter — shorter reflections, serialized essays, and behind-the-scenes notes on medicine, history, and science.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Further Reading and Evidence Behind This Story

1. Elizabeth Evans, Molly Jacobs, David Fuller, Karen Hegland, Charles Ellis. Allostatic Load and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 68, Issue 6, 2025, Pages 1072-1079,

2. Xiao Z, Li J, Luo Y, Yang L, Zhang G, Cheng X, Bai Y. Social isolation and loneliness with risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: A prospective cohort study from UK Biobank. iScience. 2024 Feb 8;27(4):109109.

3. Al Nakhebi, O.A.S.; Albu-Kalinovic, R.; Bosun, A.; Neda-Stepan, O.; Gliga, M.; Crișan, C.-A.; Marinescu, I.; Mornoș, C.; Enatescu, V.-R. Cardiovascular Diseases and Type D Personality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature of the Last 10 Years. Life2025, 15, 1061. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15071061

4.Yeh, CH., Chen, CY., Kuo, YE. et al. Role of the autonomic nervous system in young, middle-aged, and older individuals with essential hypertension and sleep-related changes in neurocardiac regulation. Sci Rep13, 22623 (2023).

5. Haapanen, M. J., Törmäkangas, T., von Bonsdorff, M., Strandberg, A. Y., & Strandberg, T. E. Midlife cardiovascular health factors as predictors of retirement age, work-loss years, and years spent in retirement among older businessmen.Scientific Reports, (2023) 13, 16526.

6. L. Corlin et al. Association of the Duration of Ideal Cardiovascular Health With Lower Risk of Incident Hypertension, Diabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, Cardiovascular Disease, and Mortality. JAMA Cardiology. 2020;5(6):667-674. Main conclusion: These results suggest that more time spent in better cardiovascular health in midlife may have salutary cardiometabolic benefits and may be associated with lower mortality later in life.

50…but from then on we learn so much. Here at 78 I’m reminded that long ago an old man told me “youth is wasted on the young”.

Thanks again for all you do.

Phil

Phil — that old line hits harder the older we get, doesn’t it? “Youth is wasted on the young” sounds cynical at 20, ironic at 50, and almost compassionate by 78. Maybe the truth is that youth has to be wasted a little — otherwise we’d never gather the kind of perspective that makes the second half of life worth living.

Thank you for sharing this — and for reminding me that the learning doesn’t slow down; it just changes direction.

Axel

This was very moving, and enlightening, to me a a woman who so often wonder what men are actually thinking! So sad to be so lonely and not really know it.Thank you for this article.

Thank you for reading it that way. One of the quiet aims of the piece was exactly that—to make something unspoken a little more visible, especially across that divide. Loneliness doesn’t always feel like sadness while you’re inside it. Often it just feels like “this is how things are.”

I’m glad it resonated.

thought provoking, powerful and sad – but with a silver lining of hope .. as someone who is in his sixties this really resonated with me .. I will be sharing this with some of my networks as it is a powerful message for us to reflect and ponder on, as always, thanks for your insights

Thank you — I’m glad it resonated. These are heavy themes, but there’s hope in naming them. I appreciate you sharing it onward.

Ahh, Doc S, I wish I had access to a doctor with your insights.

This and many of your articles ring so true. After a mild NSTEMI three years ago, I was double-stented in my RCA (a long eight weeks after the event) and told to take aspirin and statins for the rest of my life. That was it. No root cause analysis. No follow-up. Basically, thrown out the door. Now I quietly get on with life, wondering what other hidden surprises my 57-year-old body has for me. I do my own research. I get my own bloodwork. On the inside, it’s a constant worry, but on the outside I remain the dependable family man. However, I’m quieter. I can feel it. I’m there but not seen. I’m perhaps more proactive than the man in your story but it resonates so much. Thank you for all you do.