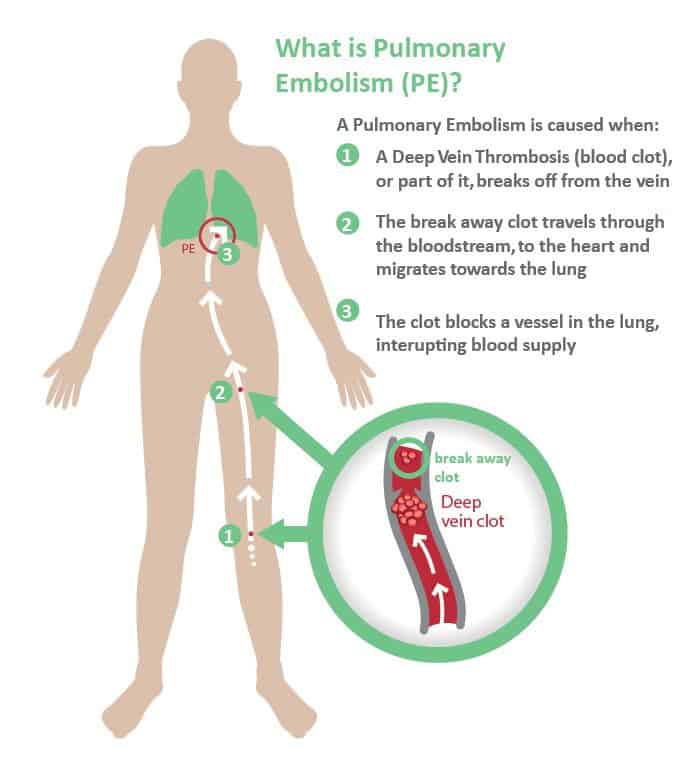

One of the most feared adverse health effects of civil aviation is the formation of blood clots in the deep veins of the lower limb, usually called deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

A part of the clot can break off and travel through the bloodstream to the lungs, causing pulmonary embolism (PE) which is a serious medical condition. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) refers to DVT, PE, or both (1)

In general, the chances of developing DVT are about 1 in 1000 per year. The cumulative chance of developing DVT over a lifetime ranges from 2 to 5 percent (2).

But what about air travel? Is it true that flying long distance can increase the risk of VTE? And, if true, what measures can be taken to reduce the risk?

Civil aviation has seen a steady increase in the number of air travelers during the last decade.

There are about 5.000 aircraft in the sky at any given time, and the number of average daily scheduled passenger flights worldwide is approximately 26.500. In 2016, the number of scheduled passenger flights was 9.7 million (3).

More than 2.5 million domestic and international passengers fly every day. The estimated number of air travelers in 2016 was 3.6 billion. That’s about 800 million more than in 2011 (4).

The term ‘economy class syndrome’ refers to the occurrence of thrombotic events during long-haul flights, mainly in economy class passengers (5).

With the aging of the population, and the increasing number of travelers with acute or chronic illnesses we might see an increase in flight-related VTE in the next few years.

What is Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)?

VTE refers to a blood clot that starts in a vein. It is the third leading vascular diagnosis, secondary to heart attack and stroke, affecting between 300,000 to 600,000 Americans each year (6).

Two clinical entities are associated with VTE; deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)

DVT is a blood clot in a deep vein, usually in the leg.

PE occurs when a DVT clot breaks free from a vein wall, travels to the lungs and then blocks some or all of the blood supply.

VTE can affect anyone but this risk is higher if certain risk factors are present.

The factors that increase the risk of VTE include a history of a recent major general or orthopedic surgery, recent fracture of the pelvis, hip bones or long bones of the lower limb, multiple trauma and lower-extremity paralysis due to spinal cord injury.

The presence of cancer increases the risk of VTE. Chemotherapy and surgery for cancer further increase the risk (7).

Other factors associated with increased risk of VTE include age, prior history of VTE, obesity, prolonged immobility, the use of oral contraceptives or estrogen treatment for menopause symptoms, and genetic conditions that affect blood clotting.

VTE refers to a blood clot that starts in a vein. Two clinical entities are associated with VTE; deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Certain risk groups are at increased risk of VTE.

What’s the Difference Between Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) and Arterial Thrombosis?

It is very important to differentiate between VTE and arterial thrombosis.

Arterial thrombosis is a blood clot that develops in an artery. It can obstruct or stop the flow of blood to major organs, such as the heart or brain.

If a blood clot blocks a coronary artery (the arterlies supplying the heart muscle with blood), it will cause a heart attack. If it blocks an artery in the brain, it will cause a stroke.

Hence, symptoms depend on where the blood clot has formed.

An arterial embolism is a blood clot that has broken free and traveled through the arteries and become stuck. An arterial embolus can block or restrict blood flow to an organ or a limb.

There is no evidence that flying increases the risk of arterial thrombosis or arterial embolism. Hence, it has not bee shown that flying increases the risk of heart attack or stroke.

Arterial thrombosis is a blood clot that develops in an artery. Hence, it is a different phenomenon than VTE. It has not been shown that flying increases the risk of arterial thrombosis.

Does Flying Increase the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)?

It is difficult to analyze the relationship between VTE and air travel. The main reason is that symptoms may not occur for several days after flying. Hence, a cause-and-effect relationship may be hard to establish.

However, there does appear to be a relationship between flight duration and the subsequent occurrence of VTE (8). The risk is greatest within the first two weeks but may be present for up to eight weeks after travel (9).

It has been estimated that the risk of VTE is approximately 2- to 4-fold increased after air travel (10). It rises with increasing flight exposure and in certain high-risk groups.

One study reported that the incidence of symptomatic VTE is 0.5 percent (one in every 4.500 flights) for flights longer than 12 hours (11).

The absolute risk is much higher if asymptomatic DVT is included and one study suggests that symptomless DVT might occur in up to 10% of long-haul airline travelers (12).

The risk of VTE is approximately 2- to 4-fold increased after air travel. It rises with increasing flight exposure and in certain high-risk groups.

What Factors Increase the Risk of Developing Flight-Related Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)?

The Multiple Environmental and Genetic Assessment (MEGA) study analyzed the risk factors for VTE associated with various modes of travel (13).

The risk flight-related VTE was similar to the risk associated with traveling by car, bus, or train, and was highest in the first week after traveling.

The study found that women on oral contraceptives have up to a 40 times greater chance of developing VTE on long-haul flights.

Overweight and obese passengers were also at increased risk for VTE on long-haul flights.

The risk of flight related VTE increases almost 20 times among passengers who have recently undergone surgery (14).

The risk is also increased among pregnant women and patients with cancer. A prior history of VTE is also a risk factor.

Tall individuals (> 6.2 feet or 190 cm) also appear to be at increased risk.

Having a particular mutation (known as factor V Leiden) in a gene involved in blood clotting increases the risk of VTE.

Pregnant women, women on oral contraceptives, overweight and obese passengers, tall individuals, and patients with cancer are at increased risk of flight-related VTE. Genetic factors also play a role.

Why Do Long-Haul Flights Increase the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)?

The increased risk of VTE during air travel may be due do several factors.

Flight atmospheric pressure inside commercial aircraft is usually maintained at levels similar to that found at altitudes of 6 – 8.000 feet (1.800 – 2400 meters) above sea level. At such heights, the partial oxygen pressure of air is 20-30 percent lower than at sea level leading to a fall in the oxygen saturation of the blood during flight.

Prolonged deficiency in the amount of oxygen reaching the tissues (hypoxia) during long flights may activate coagulation pathways in blood, increasing the risk of blood clotting.

Interestingly, long-distance travel, by both air or land, is associated with a slightly increased risk of VTE (9).

Lack of movement of venous blood in the lower limbs (venous stasis) provoked be seated positions maintained in small space for long periods appears to be an important trigger for VTE. Such circumstances are commonly encountered on long-distance travel by air or land.

Dehydration is another important factor that may contribute to VTE.

The humidity onboard commercial aircraft ranges from 6-18% depending on the compartment (15). Optimal humidity varies between 40-70%. Hence, cabin air very dry.

Drinks that are known to increase urination, such as alcoholic beverages, coffee and tea, may increase the risk of dehydration.

There is a clear relationship between the length of flight and the risk for VTE.

Overall, the risk of VTE is increased twofold in long-distance flights (>8 h). The risk is 26% higher for each 2-hour increase in travel duration (16).

Long-haul flights are associated with an increased risk of VTE. The risk increases with the length of travel.

Economy Class Syndrome and Window Seating. Does it Matter Where One Sits?

Despite the term ‘economy class syndrome’ being used frequently to describe flight-related VTE, there appears to be a small difference between passengers traveling on economy and business class.

One study found that passengers who travel in a window seat are at double risk of DVT compared to passengers traveling in aisle seats (17).

Overweight subjects with a window seat seem to be at particularly high risk.

Being anxious or sleeping during the flight also appears to icreas risk.

There may be a slightly lower risk of VTE among patients flying business class compared to economy class. Passengers who travel in window seats appear to be at higher risk than passengers traveling in aisle seats.

Are Commercial Airline Pilots and Flight Attendants at Increased Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)?

Because of the increased risk of flight-related VTE, commercial airline pilots and cabin crew may be at increased risk.

It has even be suggested that pilots may be at higher risk than cabin crew because they undertake less physical activity during flight.

In Dutch study of 2.630 airline pilots, the rate of VTE was 0.3 per 1.000 each year. This incidence rate is slightly lower than in the general population (18).

The risk did not increase with number of flight-hours per year and was not associated with the ranks of the pilots.

A review of the database of the Civil Aviation Authority for 1990–2000 shows 27 cases of VTE. The mean population at risk over the whole period was 9775, which yields an approximate incidence of 0·2 per 1000 each year which is lower than in the general population (19).

A large study from Harvard University published 2018 aimed at estimating the health consequences of flight attendant work relative to the general population (20).

The study showed that flight attendants had a higher prevalence of fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and all cancers. However, the risk of VTE was not increased compared to the general population.

It has not been shown that commercial airline pilots and flight attendants are at increased risk of VTE.

What General Measures May Help Prevent Flight-Related Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)?

Several underlying factors may be responsible for the increased risk of VTE during long-haul flights.

Immobility appears to be an important factor. Hypoxia and dehydration may also contribute.

Alcohol consumption may theoretically promote both immobility and dehydration.

Preventive measures are not necessary for most travelers. However, in individuals at risk on flights of six hours or more, preventive measures may be recommended.

Individuals at risk for flight-related VTE may benefit from simple measures such as frequent ambulation, calf muscle stretching, sitting in an aisle seat if possible, or the use of below-knee graduated compression stockings (21).

Avoidance of dehydration, alcohol or other sedatives is recommended. Water is preferred rather than beverages containing caffein (sucha s coffee or tea) which may promote diuresis.

Below-knee graduated compression stockings (15 to 30 mmHg pressure at the ankle) may help reduce the risk of VTE (22).

For long-distance travelers who are not at increased risk for VTE, the current guidelines suggest against the use of below-knee graduated compression stockings (20).

Individuals at risk for flight-related VTE may benefit from simple measures such as frequent ambulation, calf muscle stretching, sitting in an aisle seat if possible, or the use of below-knee graduated compression stockings. Avoidance of dehydration, alcohol or other sedatives is recommended.

Can Pharmacologic Prophylaxis Help Prevent Flight-Related Venous Thromboemboslism (VTE)?

Data are insufficient when it comes to the administration of routine pharmacologic measures.

Recently there has been a tendency in health care to administer pharmacologic VTE prevention for every patient, regardless of risk. As a result, many patients may receive unnecessary therapies that provide little benefit and could have adverse effects.

Current guidelines do not recommend the use of aspirin or anticoagulant therapy to prevent VTE in long-distance travelers (21).

For travelers who are considered to be at particularly high risk for VTE, the use of antithrombotic agents should be considered on an individual basis because the adverse effects may outweigh the benefits.

In patients who are already receiving anticoagulation (blood thinning drugs), no additional measures to prevent VTE are needed (9).

Platelet inhibitors such as aspirin have not been shown to prevent flight related VTE (8).

Some studies suggest that low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) may help prevent flight-related VTE. For example, enoxaparin at a dosage of 1 mg/kg, via subcutaneous injection, 2-4 hours before departure appears to significantly reduce the risk of VTE on long-haul flights (8).

The used of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACSs) such a as dabigatran rivaroxaban, apixapan, edoxaban) for the treatment and prevention of VTE has increased in recent years.

Although these drugs appear promising, studies have not been conducted to confirm their efficacy and safety for preventing flight-related VTE. (23)

Current guidelines do not recommend the use of aspirin or anticoagulant therapy to prevent VTE in long-distance travelers. For travelers who are considered to be at particularly high risk for VTE, the use of antithrombotic agents should be considered on an individual basis because the adverse effects may outweigh the benefits.

The Bottom Line

VTE refers to a blood clot that starts in a vein. Two clinical entities are associated with VTE; deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

The risk of VTE is approximately 2- to 4-fold increased after air travel. It rises with increasing flight exposure and in certain high-risk groups.

Long-haul flights in particular are associated with an increased risk of VTE. The risk increases with the length of travel.

Pregnant women, women on oral contraceptives, overweight and obese passengers, tall individuals, and patients with cancer are at increased risk of flight-related VTE. Genetic factors also play a role.

There may be a slightly lower risk of VTE among patients flying business class compared to economy class. Passengers who travel in window seats appear to be at higher risk than passengers traveling in aisle seats.

Commercial airline pilots and flight attendants do not appear to be at increased risk of VTE.

Individuals at risk for flight-related VTE may benefit from simple measures such as frequent ambulation, calf muscle stretching, sitting in an aisle seat if possible, or the use of below-knee graduated compression stockings.

Avoidance of dehydration, alcohol or other sedatives is recommended.

Current guidelines suggest against the use of aspirin or anticoagulant therapy to prevent VTE in long-distance travelers.

However, for travelers who are considered to be at particularly high risk for VTE, the use of antithrombotic agents should be considered on an individual basis because the adverse effects may outweigh the benefits.

Discover more from Doc's Opinion

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.