Estimated reading time: 19 minutes

“The 37th President Is First to Quit Post.”

— The New York Times, August 9, 1974

In just a few blunt words, the New York Times closed the book on Richard Nixon.

The next morning, standing before a weary nation, Gerald Ford offered something like absolution. In his first speech as president, he spoke a single, unforgettable line:

“My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over.”

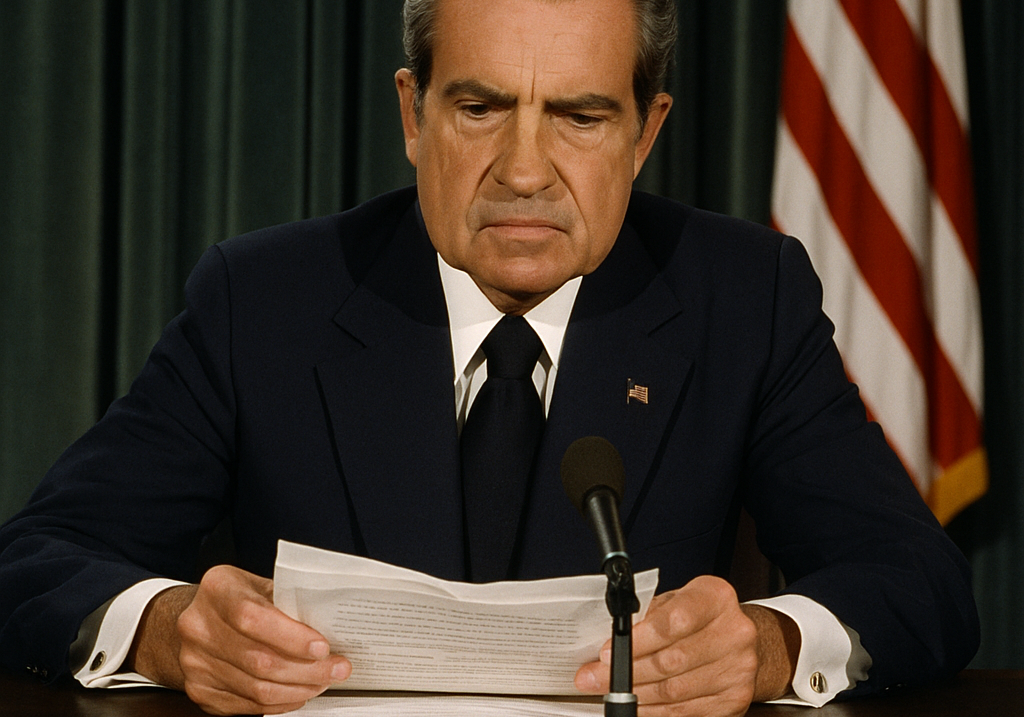

Before the Cameras Rolled – August 8, 1974, 9:01 PM

The room was still. Hot lights glared. The same desk where presidents had signed declarations of war now held a small stack of paper, creased and already damp from his hands.

He sat alone. No advisors. No whispered notes. Just the soft hum of cameras and the scent of sweat and old upholstery.

He looked down at the page.

“I have never been a quitter…”

He whispered the line once, then again—testing it, rehearsing it. It didn’t sound right. Too polished. Too final.

Haldeman was gone. Ehrlichman, gone. Kissinger had vanished into foreign affairs. The friends had fallen away one by one, like leaves in the wind.

“I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But…as President, I must put the interests of America first.”

Oval Office, resignation night.

The red light blinked on. Three… two… one.

He drew a breath.

And so the end began.

The Witching Hour

It’s long past midnight in the White House, and the tape is still rolling.

Richard Nixon is pacing. The microphones hidden beneath his desk catch his voice, slurred, muttering, looping back on itself like a man stuck in a spiral. He speaks in half-thoughts about Jews, the press, Kennedy, his enemies, real and imagined. He repeats himself. He argues with no one. And then silence.

He’s been drinking. Again. His aides call this “the witching hour.”

Behind closed doors, Nixon’s nights had become rituals of isolation. Aides had long since gone to bed. The Secret Service lingered outside his quarters. Inside, he wandered the halls of the residence—sometimes with a scotch in hand, sometimes sedated by the off-label anti-seizure drugs his physician prescribed for mood stabilization. The combination blurred the lines between reality and illusion.

One night, a staffer reported, “he was talking to the portraits on the wall.”

By day, Nixon played the part of a scientific visionary. He stood before cameras in December 1971, pen in hand, declaring a bold new front in public health: the War on Cancer. His voice was clear then. His eyes steady. “We can cure cancer in our time,” he said.

But the man who promised to conquer cancer was quietly losing control of his own mind.

The tapes—so many of them—would later expose the truth: not just political paranoia or criminal intent, but something more intimate. A broken man. A mind under siege from within. Sedatives, scotch, and solitude—a deadly cocktail behind the seal of the presidency.

He had declared war on disease. But the real battle was much closer.

It was Nixon vs. Nixon.

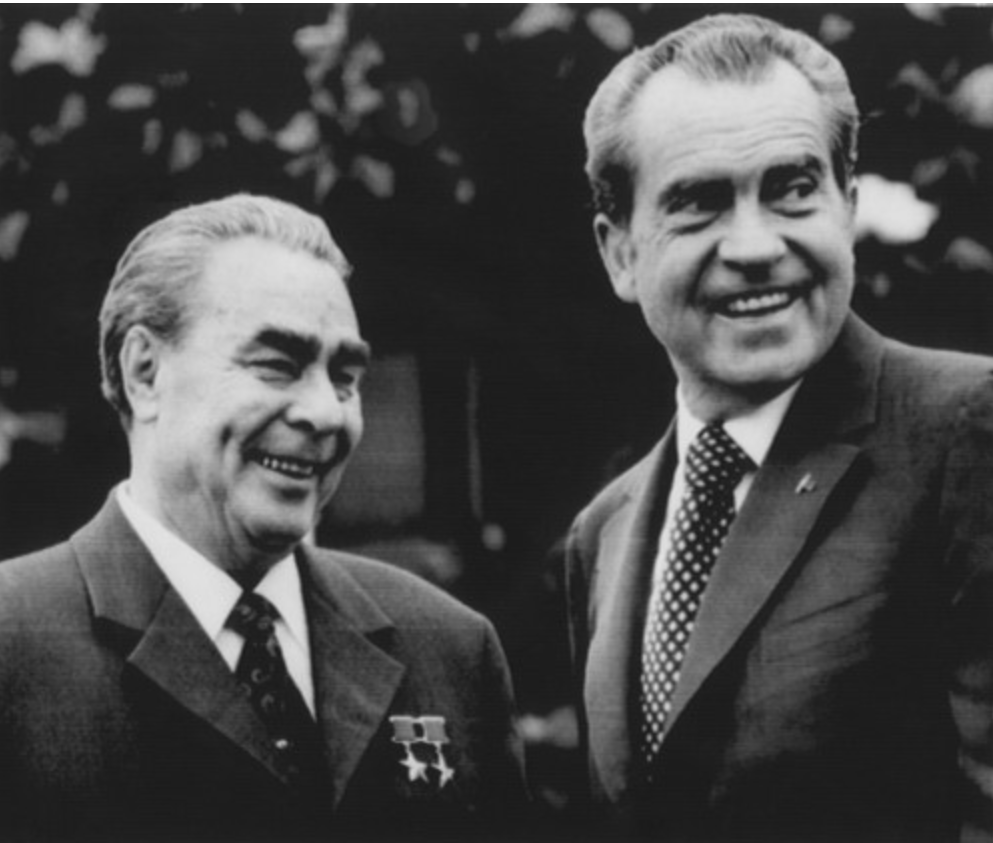

The China Smile

February 1972. Beijing.

The red carpet stretched before him. Zhou Enlai extended a hand. Cameras flashed. Nixon, flanked by diplomats and the Secret Service, stepped onto the tarmac of a Communist nation and into history.

He smiled. Stiffly, but he smiled.

It was the performance of a lifetime.

Later that night, back in his hotel, he was alone. The applause had faded, and the fatigue set in. He reviewed briefing notes under lamplight and stared out at the unfamiliar skyline. There were no calls, no aides, no whispers in the next room. Just the muffled quiet of victory and the rising anxiety that came with it.

The press called it a masterstroke. A bold opening. A statesman’s pivot.

But Nixon, ever the strategist, knew better than to trust the moment. Applause faded. Enemies regrouped. Control was never permanent.

He had won the evening.

But morning would come.

At home, scandal loomed—but abroad, Nixon was reshaping the Cold War.

The Sick Presidency

He liked to speak in absolutes: strength, order, victory.

Nixon admired toughness in men—Eisenhower’s stoicism, de Gaulle’s endurance, Churchill’s grit. His public image followed suit: a stiff, serious commander of history, jaw clenched, words deliberate.

Weakness—especially of the body or mind—was something to be hidden, denied, buried beneath ceremony.

But Nixon’s body had other plans.

Though he rarely showed signs of physical illness in public, he was far from well during much of his presidency. Behind the scenes, Nixon suffered from a constellation of chronic issues—some medical, some psychological, many blurred by secrecy.

One chronic physical condition did appear in his medical chart: phlebitis—painful inflammation of the veins, most often in the legs. It flared, receded, returned. But it was rarely discussed. And far from the most destabilizing threat he carried.

Then there was the matter of medication.

Nixon took Dilantin (phenytoin), a drug typically used to treat epilepsy. But Nixon did not have epilepsy. His physician—first Dr. Walter Tkach, later Dr. John Lungren—reportedly prescribed it off-label to stabilize Nixon’s mood and manage what some described as “emotional storms.”

He also used sleeping pills and tranquilizers, though the full list of medications remains unclear.

And there was alcohol. Aides referred to it cautiously, if at all. But according to multiple sources—including journalist Seymour Hersh and biographer Richard Reeves—Nixon drank frequently, especially at night, and sometimes excessively.

In 1973, as Watergate closed in, Defense Secretary James Schlesinger quietly instructed military officials to route any nuclear launch orders through him out of fear Nixon might not be stable enough to give them.

This wasn’t just about illness. It was about fitness, trust, and the dangerous intersection of power and fragility.

The Clot

September 8, 1974. Less than a month after his resignation.

Nixon collapsed at his home in San Clemente, California. The phlebitis that had plagued him throughout his presidency had progressed to a deep vein thrombosis. The clot dislodged and traveled to his lungs, causing a pulmonary embolism—a life-threatening blockage of the pulmonary arteries. He was rushed to Long Beach Memorial Hospital.

It wasn’t just a medical emergency. It was a perfect metaphor.

Because that very same day, back in Washington, President Gerald Ford issued a full pardon to Nixon for any crimes he may have committed while in office.

As Nixon lay recovering from a clot that nearly killed him, he was simultaneously rescued from criminal prosecution.

Two forms of salvation. One from a blood clot. The other from the Constitution.

The pardon, however, came at a cost—not just to the nation’s sense of justice, but to Ford himself. The decision outraged much of the public, and what Ford had intended as a gesture of healing quickly became a political liability.

His approval ratings plummeted. Accusations of a secret deal followed him for years. He even became the first sitting president to testify before Congress about the decision.

In the 1976 election, the pardon resurfaced as a symbol of insider protection and damaged credibility, helping tip the race in Jimmy Carter’s favor. Ford would later defend the move as necessary to “close the book” on Watergate. But politically, it was a wound he never fully recovered from.

But the clot was only the beginning. In the weeks that followed, Nixon remained fragile. By October, he was back in the hospital—this time for a serious gastrointestinal bleed, likely a complication of the blood thinners prescribed after his embolism.

And yet, the public response was not purely scornful. Despite the fury of Watergate, the hospital switchboard was jammed with sympathetic calls. Thousands of letters poured in. One room was filled entirely with flowers. The man who had resigned in disgrace now lay in bed, physically broken—but not without a measure of national compassion.

President Ford came to visit. The exchange was brief and awkward. “Did you have a good night?” Ford asked. Nixon, propped up in bed, replied: “None of the nights are too good.” Afterward, Ford told reporters, “Obviously, he’s a very sick man. But I think he’s coming along well.”

Not everyone was moved. California Governor Ronald Reagan, when told Nixon was critically ill, responded with cutting detachment: “Maybe that will satisfy the lynch mob.”

It was December 1971, and Nixon needed a win.

Vietnam dragged on. The protests weren’t stopping. The Pentagon Papers had exposed the machinery of deceit. And somewhere in the walls of the Executive Office Building, the first Watergate tape had already begun recording.

But in the East Room of the White House, the mood was brighter. Cameras flashed as Nixon signed the National Cancer Act, flanked by smiling lawmakers and medical officials. He spoke of hope, science, destiny. Of America’s “dread disease” finally meeting its match.

“The time has come for intense and coordinated research that can lead to a cure.”

The War on Cancer wasn’t just a public health initiative. It was a carefully staged political maneuver. Nixon, ever the tactician, saw in cancer a rare opportunity: a bipartisan issue with moral clarity, a battle he could frame in patriotic terms without the quagmire of foreign policy or scandal.

It offered something he badly needed: the image of control.

Cancer was the perfect enemy—silent, internal, dangerous. Beating it could make him a statesman. Losing to it would look like weakness. Nixon wanted to dominate history, not just survive it.

But cancer wouldn’t cooperate.

The public expected a cure within five years. The science wasn’t close. Tumor biology was more complex than anyone had imagined. Genes, cellular signaling, and tumor diversity – these were not things easily conquered by money or political will.

As the science stalled, the headlines shifted elsewhere.

To leaks. To subpoenas. To the now-infamous tapes.

Within two years, Nixon’s moonshot had faded from public view—eclipsed by a scandal that metastasized faster than any cancer.

The War on Cancer became a footnote, while Watergate consumed the front pages and Nixon’s credibility bled out by the day.

In trying to cure America, he lost control of the story—and became its casualty.

The Shadow Cabinet

The official White House physician was Dr. Walter Tkach. Then Dr. John Lungren. But they weren’t the only ones treating Richard Nixon.

Behind the scenes, a quieter, more peculiar figure hovered at the edge of power: Dr. Arnold Hutschnecker, a New York psychiatrist with a taste for authoritarian order and a soft spot for troubled presidents.

Nixon had first seen Hutschnecker in the 1950s—initially as a patient, later as something stranger. Not quite therapist. Not quite advisor. Something closer to a psychological consultant for the presidency. He believed, in Nixon’s own words, that “mental health and leadership” were inseparable—and that “civilizations collapse when their leaders go insane.”

Privately, Nixon trusted him. Or perhaps he simply liked that Hutschnecker validated his view of the world: suspicious, hierarchical, embattled. In 1970, Nixon even floated a plan—half serious, half chilling—to screen all schoolchildren for psychological problems, using Hutschnecker’s methods. The idea was dropped after public backlash. But the mindset lingered.

Hutschnecker wasn’t the only unusual figure in Nixon’s medical orbit. The president also relied on a patchwork of doctors—some personal, some political. He distrusted the press, the bureaucracy, and even his own Cabinet. So why would medicine be any different?

The result was a kind of shadow cabinet of care, where secrecy trumped continuity and where the goal wasn’t always health but control.

This was how Nixon preferred it. Confidential. Compartmentalized. Loyal.

He didn’t want a healer. He wanted a handler.

And in the growing darkness of his presidency, medical truth—like political truth—was just one more thing to be managed.

Why Was Nixon Called “Tricky Dick”?

The nickname “Tricky Dick” first took hold during Nixon’s 1950 Senate campaign against Democrat Helen Gahagan Douglas. He ran an aggressive, often underhanded campaign—implying she had communist sympathies and printing her materials on pink paper to stoke red scare fears.

The name stuck. Over time, it came to represent Nixon’s broader political reputation: cunning, secretive, and obsessed with control. During the Watergate era, “Tricky Dick” reentered public vocabulary—not just as a jab, but as a symbol of a presidency that ran on loyalty, surveillance, and hidden levers of power.

It began as an insult—but ended as prophecy.

He hated the nickname. But he earned it.

The Descent

By mid-1973, the walls had begun to close in.

Subpoenas were flying. Aides were flipping. The tapes—his tapes—had become both evidence and enemy. The country watched the Watergate hearings in prime time, but what unfolded behind the White House doors was far more disturbing than anything on television.

Nixon stopped sleeping.

He prowled the halls late at night, talking to himself, replaying grievances aloud, muttering about enemies real and imagined. Staff learned to avoid him after dark. He drank more. He grew erratic.

The cocktail of sleeplessness, despair, and mood-altering substances hollowed him out. Phone calls to old allies—Kissinger, Haig, even Bebe Rebozo—could veer from confessional to combative in minutes.

Some nights, he’d disappear into the Lincoln Sitting Room and replay the tapes for hours, listening to his own voice like a man searching for vindication—or perhaps evidence of betrayal.

Even Henry Kissinger, ever the loyal operator, grew concerned. “The president,” he said quietly, “is not well.”

What they witnessed was more than stress. It was a psychological unraveling. Nixon—never an easy man—was now barely holding himself together. Aides described him as pale and bloated, moving stiffly, his speech sometimes slurred in the evenings. The insomnia was relentless. The phlebitis flared again.

There were whispers of depression. Rumors of breakdown. Talk of pills and too many drinks.

He grew paranoid—obsessed with enemies, both real and imagined. He spoke of betrayal with biblical overtones. He saw himself as a martyr, not a president—crucified by history, persecuted by the press. Watergate wasn’t just a scandal; it was a conspiracy. Divine punishment. A test of endurance.

There were nights when Nixon seemed to teeter on the edge of something darker. According to H.R. Haldeman, he once raised the subject of suicide. They talked him down. But no one forgot.

While Nixon was never formally diagnosed with a psychiatric condition, extensive firsthand reports suggest he exhibited symptoms consistent with major depression, paranoid ideation, emotional lability, and possible substance-induced mood disorder. His off-label use of phenytoin, reliance on sedatives, and long stretches of insomnia add clinical weight to descriptions of severe psychological strain.

By the spring of 1974, the White House had become a bunker of dread. Curtains were drawn. Conversations were whispered. Nixon sat alone with the tapes, staring into the eyes of his enemies—and hearing only his own voice in return.

The country saw Watergate.

But those closest to him saw something worse: a man vanishing inside himself. Not just a president falling from power—but a psyche folding under the weight of its own mythology.

And then, just as the walls began to collapse, he did something no one expected.

He left.

What Did Nixon Do Wrong in Watergate?

The Watergate scandal began with a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in June 1972, carried out by operatives linked to Nixon’s reelection campaign.

Nixon did not order the break-in—but he abused presidential power to cover it up. He authorized payments to silence the burglars, directed aides to obstruct the FBI investigation, and tried to use the CIA to block inquiries.

The White House taping system—installed at Nixon’s direction—captured these efforts on tape. When the tapes were subpoenaed, Nixon refused to release them, triggering a constitutional crisis.

In the end, it was not the crime—but the cover-up—that forced his resignation.

Exit Wounds

August 9, 1974.

The helicopter lifted off from the South Lawn. Nixon’s right arm rose in one last V-sign, fingers splayed, jaw clenched. Then he disappeared inside.

It was the first time an American president had resigned. The cameras captured the departure. The world saw a man leaving office.

But they didn’t see what came next.

Nixon flew west—not just geographically, but psychologically. His destination was San Clemente, California. But he might as well have been heading into exile.

The house was large but sterile. The phones stopped ringing. The aides went home. The silence that followed the roar of Washington wasn’t peace—it was vacuum.

“He was like a man who’d died,” one friend later said. “But hadn’t been buried.”

He was recovering from more than scandal. His health had fractured under the weight of stress, sleeplessness, and self-medication. The blood clot that nearly killed him—the same one that struck on the day of his pardon—had left scars deeper than tissue. It was a reminder: the body keeps score, even when history moves on.

In San Clemente, Nixon became a ghost of his former self. He spoke rarely, slept poorly, drank often. The Watergate tapes were sealed away. The newspapers continued to arrive, but he often refused to read them. He took long, solitary walks along the coast, avoiding cameras and questions.

For a man obsessed with legacy, the silence was unbearable. He began writing memoirs, foreign policy essays, and self-justifications. Not to confess but to reclaim. He wanted to frame his story before history did it for him.

But the shame lingered.

Even in private, he could not say the word resignation without bitterness. To him, Watergate was not a crime. It was a tragedy—the kind that befalls the misunderstood. He saw betrayal, not guilt. Fate, not flaw.

He never again held office.

But he never stopped trying to exert control over the story—to win in prose what he lost in power.

He had been the architect of control, tapes, loyalty oaths, and war rooms. But in the end, he could not command the one thing he feared most.

Oblivion.

Epilogue: The Final Edit

In the years following his resignation, Richard Nixon continued to write.

Memoirs, letters, foreign policy manifestos—an unending effort to revise the public record. He no longer held office, but he still fought for the final word.

He returned to China. He advised presidents. He filled his days with carefully staged reentries—briefings, interviews, annotated headlines. His study in New Jersey was lined with portraits of world leaders and shelves of books, many authored by himself.

But even as Watergate shadowed his memory, Nixon knew the world stage told a different story. He had changed history with China, broken diplomatic ground with Moscow, ended the draft, and redrew America’s Cold War posture.

In private, he spoke often of Zhou Enlai, of Brezhnev, of the SALT talks, and the day he first stepped onto Chinese soil. Those victories, he believed, would outlast the scandal. In moments of candor, even his critics agreed: few men had shifted global power so decisively—and from such unlikely beginnings.

In 1977, three years after his resignation, Nixon sat down for a series of televised interviews with British journalist David Frost. The setting was subdued. The tone, rehearsed. But the stakes were high.

For Nixon, it was a chance to reclaim his voice. For the public, it was the final cross-examination. In a moment that surprised even his critics, Nixon admitted: “I let the American people down.” It wasn’t quite an apology—but it was the closest he would come.

There’s no recording of his final days. No last dictation. Just a stroke in April 1994 that left him speechless. Four days later, he died—no cameras, no tapes, no farewell address. He was 81 years old.

At Nixon’s funeral, Henry Kissinger offered a eulogy as careful as it was honest. “Richard Nixon’s life was a perpetual striving,” he said. It was meant as tribute—but it was also true. Nixon had spent his entire life climbing, defending, rewriting—never quite able to rest, even in exile

And Bill Clinton, who had once marched against Nixon’s war, added a plea of grace:

“May the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close.”

Whether that day ever came is uncertain.

But the attempt to see him whole—flawed, brilliant, paranoid, tireless—may be the only honest tribute.

Next in the Series

He built a legacy at home while fire rained abroad.

The pressure never let up. The war wouldn’t end. And the clock in his chest kept ticking.

He ruled like a man on borrowed time—because he was.

The Heart of Power – Lyndon B. Johnson: The Ticking Man

Previous:

Episode 1. The Heart of Power: When Metabolic Disease Entered the Oval Office – William Howard Taft

Episode 2. The Heart of Power: The Golf Course Heart Attack – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Episode 3. The Heart of Power: The Stroke That Silenced a Dream – Woodrow Wilson

Episode 4. The Heart of Power: Built To Stand, Bound To Fall – John F Kennedy

Episode 5. The Heart of Power: Where Strength Sat Still – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Episode 6. The Heart of Power: The Ride Into the Sunset – Ronald Reagan

📚 Sources & Further Reading

Woodward, Bob, and Carl Bernstein. The Final Days. Simon & Schuster, 1976.

Behind-the-scenes reporting on Nixon’s psychological and political collapse.

Reeves, Richard. President Nixon: Alone in the White House. Simon & Schuster, 2001.

A vivid account of Nixon’s isolated governing style and emotional decline.

Ambrose, Stephen E. Nixon: The Triumph of a Politician 1962–1972. Simon & Schuster, 1989.

Essential context on Nixon’s worldview, ambition, and political strategies.

Hersh, Seymour M. “The Pardon – Nixon, Ford, Haig, and the transfer of power.” The Atlantic, October 1983.

A close look at Nixon’s mental state and its national security implications.

Time Magazine. “The Ex-President: Nixon—Surgery, Shock and Uncertainty.” TIME, October 14, 1974. https://time.com/archive/6845332/the-ex-president-nixon-surgery-shock-and-uncertainty/

National Archives and Records Administration. Nixon Presidential Materials Collection. Official overview of the Nixon-era documents, audio tapes, and archival policies.

The American Presidency Project. “Address to the Nation Announcing Decision To Resign the Office of President of the United States.” August 8, 1974. Read full transcript.

CNN Original Series. Tricky Dick (2019).

A four-part documentary examining Nixon’s rise and fall through archival footage and commentary. Link.

Some portions of this article were developed with support from ChatGPT, an AI tool created by OpenAI. It was used to assist with research synthesis, narrative structure, and language refinement. All medical content, historical analysis, and editorial decisions were independently reviewed and finalized by the author.