Estimated reading time: 20 minutes

Author’s note (2025 update)

This article was originally published in 2017 and revised in 2021. It has now been updated and expanded for 2025 to include new clinical insights, refined explanations, and additional causes of chest pain.

Chest pain is one of the most common—and most alarming—symptoms in medicine.

In the United States, millions of people visit emergency departments each year because of it.

For patients, chest pain often triggers one thought above all others: heart attack.

For doctors, it opens a complex puzzle.

If chest pain is severe, lasts more than a few minutes, or is accompanied by shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, or fainting — call emergency services immediately.

Do not try to drive yourself to the hospital. Every minute counts.

The truth is that chest pain has many faces. Some causes are life-threatening—like a heart attack, aortic dissection, or pulmonary embolism. Others are relatively harmless—like muscle strain, acid reflux, or anxiety. The challenge lies in telling them apart quickly and safely.

That’s why nearly every emergency department now treats chest pain as “cardiac until proven otherwise.” High-sensitivity troponins, structured risk scores, and coronary CT angiography have transformed evaluation—but the basics remain unchanged: listen to the story, examine carefully, and think broadly.

In this guide, we’ll walk through 20 important causes of chest pain, grouped into six categories:

- Cardiac (heart conditions)

- Pulmonary (lung conditions)

- Gastrointestinal (digestive disorders)

- Musculoskeletal (bones, muscles, tendons)

- Psychiatric (anxiety and panic disorders)

- Other causes (such as drug effects or shingles)

How Doctors Think About Chest Pain

- History is the most powerful test. Where is it? When did it start? What makes it better—or worse?

- Quality. Pleuritic (worse with breathing) suggests pleura/lung; pressure or heaviness suggests myocardium; pain reproduced by palpation or movement favors chest wall.

- Duration. Seconds → rarely cardiac. Pain unchanged for weeks → almost never angina. Sudden, severe, “tearing” pain that may migrate → consider aortic dissection.

- Provocation. Exertional (angina), positional (pericarditis better sitting forward), with swallowing (esophageal), or with movement/tenderness (musculoskeletal).

- Radiation. To neck, jaw, or arms favors coronary ischemia.

- Bottom line. If chest pain is severe, prolonged, or accompanied by dyspnea, diaphoresis, nausea, or syncope—treat it as cardiac until proven otherwise.

Cardiac Causes – Heart Conditions Causing Chest Pain

1. Heart Attack/Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)

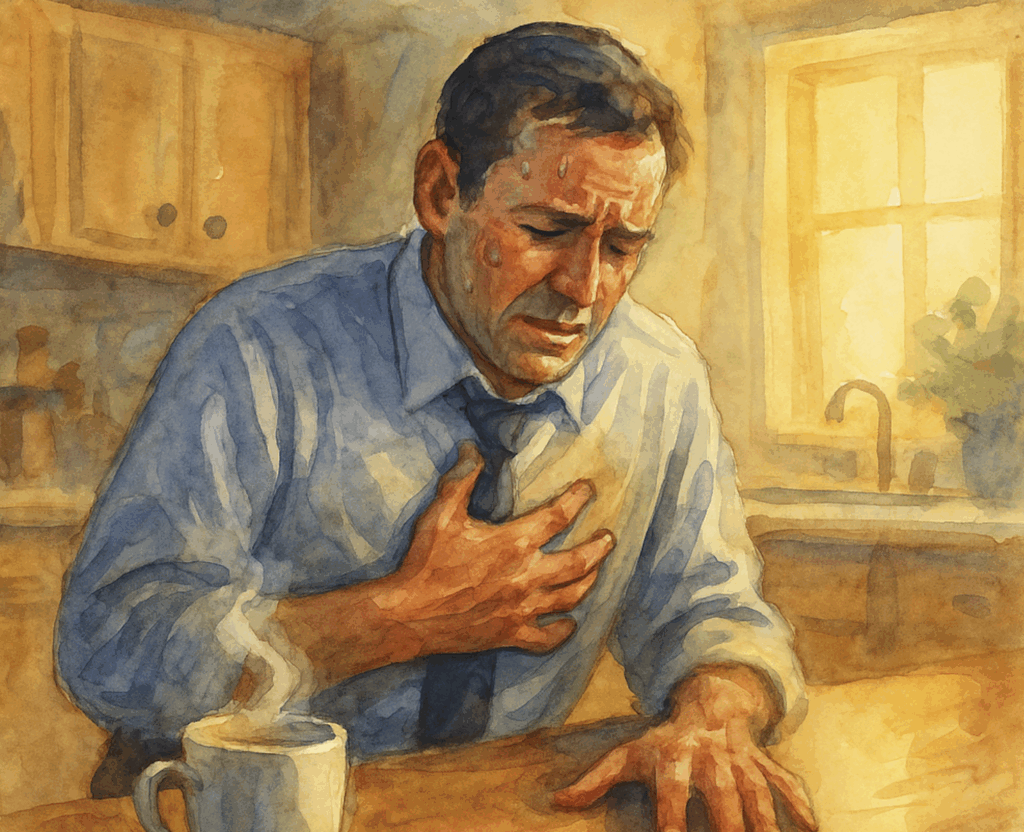

It often begins quietly.

A man in his sixties, sitting at the breakfast table, feels a strange pressure beneath his breastbone. Not pain exactly — more like a weight pressing from the inside. He stands, takes a breath, and it doesn’t go away. The feeling spreads to his left arm, then to his jaw. Sweat beads on his forehead. In that moment, part of his heart muscle is suffocating.

This is a heart attack, or acute coronary syndrome (ACS) — the sudden blockage of blood flow through a coronary artery. Without oxygen, heart cells begin to die within minutes.

What Actually Happens

Most heart attacks begin not with a fixed narrowing, but with a rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque. When its thin fibrous cap tears, platelets rush in to seal the injury. A clot forms, but instead of healing, it closes the artery entirely.

Downstream, the heart muscle starves for oxygen. The result is myocardial infarction — permanent injury to the heart.

Symptoms and Presentation

Pain is typically pressure, fullness, or heaviness in the chest, often radiating to the arm, neck, jaw, or back.

Sweating, nausea, and breathlessness are common.

Women, older adults, and people with diabetes may have atypical symptoms like fatigue or indigestion.

Diagnosis

- ECG to detect ischemic changes.

- High-sensitivity troponin to confirm injury.

- Coronary angiography or CT angiography to visualize blockage.

Emergency departments now use structured chest pain pathways to balance speed with safety.

Treatment

The goal is simple: restore blood flow quickly.

Angioplasty and stent placement (PCI) are preferred. If unavailable, thrombolytic therapy may dissolve the clot.

All patients receive aspirin, antiplatelet therapy, and anticoagulation, followed by beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and statins to stabilize the artery.

Key Takeaway

A heart attack is the last chapter of a long, silent story of arterial injury.

Pain that is severe, lasts more than a few minutes, or occurs at rest should never be ignored.

Call emergency services immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t drive yourself. Just call.

2. Angina Pectoris

If a heart attack is the explosion, angina is the warning tremor before it.

It’s a heaviness in the chest during exertion, fading with rest — a signal that the heart’s oxygen demand exceeds its supply.

What Actually Happens

Angina occurs when a coronary artery is narrowed but not fully blocked. During exercise or stress, demand rises but supply cannot keep up.

Types and Triggers

- Stable angina: predictable, relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

- Unstable angina: new, worsening, or occurring at rest — a red flag.

- Vasospastic (Prinzmetal) angina: due to transient spasm.

- Microvascular angina: smaller vessels fail to dilate properly.

Diagnosis

Stress testing and CT coronary angiography (CCTA) help identify ischemia.

FFR-CT and CT perfusion add precision.

Treatment

Lifestyle modification, beta-blockers, nitrates, and calcium-channel blockers.

If symptoms persist, angioplasty or bypass surgery may be required.

Key Takeaway

Angina is the heart’s alarm bell. It deserves respect, not dismissal.

3. Aortic Dissection

It happens without warning — a tearing pain that splits through the chest and radiates to the back.

This is aortic dissection, one of the most dangerous causes of chest pain.

What actually happens

The inner layer of the aorta tears, and high-pressure blood surges between the wall layers, creating a false channel. The dissection can extend up or down the aorta, cutting off blood supply to vital organs or rupturing outward into the chest cavity.

Why it happens

Most cases occur in patients with long-standing hypertension.

Other risk factors include Marfan syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, and prior cardiac surgery. Cocaine and extreme emotional stress can also trigger it by acutely raising blood pressure.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Pain is abrupt, severe, and described as tearing or ripping, often migrating as the dissection extends.

Unequal pulses or blood pressure in the arms are classic clues.

Diagnosis relies on CT angiography, which shows the true and false lumens of the aorta. In unstable patients, transesophageal echocardiography is used at the bedside.

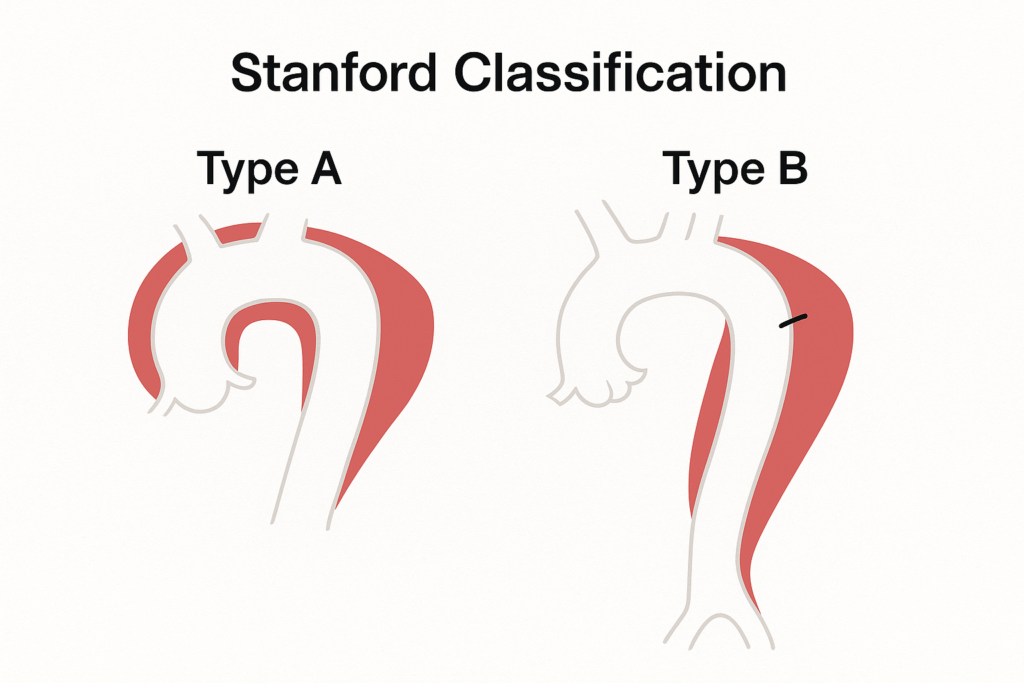

Treatment

Dissections involving the ascending aorta (Type A) require immediate surgery.

Those confined to the descending aorta (Type B) are usually managed medically with blood pressure and heart rate control to reduce wall stress.

Even with prompt care, mortality rises with every passing hour.

Key takeaway

Aortic dissection is rare but can be lethal. Sudden, tearing pain that radiates to the back is never “just a pulled muscle.” It’s an emergency until proven otherwise.

4. Pericarditis

Chest pain that changes with position — worse when lying down, better when sitting forward — often points to the pericardium, the sac surrounding the heart.

When that sac becomes inflamed, every heartbeat rubs against it, producing pain that can mimic a heart attack.

What actually happens

Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardial layers, most often due to viral infection, though it can follow heart surgery, autoimmune disease, or myocardial infarction.

Symptoms and signs

Pain is sharp and pleuritic, radiating to the shoulder or neck. It may worsen with inspiration or swallowing.

A classic finding is a pericardial friction rub, a scratchy sound heard with the stethoscope.

Unlike infarction, pain often improves when the patient sits upright.

Diagnosis

- ECG: diffuse ST-segment elevation and PR depression.

- Echocardiography: checks for pericardial effusion.

- Blood tests: may show elevated inflammatory markers.

Treatment

Most cases resolve with NSAIDs or colchicine.

Corticosteroids are reserved for recurrent or resistant cases.

Hospitalization is needed only when large effusions or tamponade are suspected.

Key takeaway

Pericarditis is painful but usually benign. The position-dependent pain pattern distinguishes it from more dangerous causes.

5. Stress Cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo)

Heartbreak can mimic a heart attack.

A sudden loss, an argument, or emotional shock triggers chest pain, ECG changes, and elevated troponin — yet the coronary arteries are perfectly open.

What actually happens

Known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (from the Japanese word for an octopus trap), this condition occurs when a surge of stress hormones stuns the heart muscle, causing the left ventricle to balloon outward temporarily.

It predominantly affects postmenopausal women and often follows emotional or physical stress.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Chest pain and shortness of breath appear suddenly.

ECG and troponin tests resemble a heart attack, but coronary angiography shows no obstruction.

Echocardiography reveals the characteristic “ballooned” shape of the ventricle.

Treatment and prognosis

Supportive care and standard heart failure therapy are usually enough.

The ventricle typically recovers fully within weeks, though recurrence can occur in a minority of patients.

Key takeaway

Takotsubo reminds us that emotion and physiology are inseparable — the heart listens, and sometimes it breaks.

6. Aortic Stenosis

Chest pain doesn’t always come from blocked arteries. Sometimes it comes from a valve that no longer opens fully.

In aortic stenosis, the valve between the heart and the aorta becomes narrowed, forcing the heart to work harder to eject blood.

What actually happens

Over years, the valve leaflets thicken and calcify.

The left ventricle grows stronger but stiffer, raising pressure and oxygen demand.

When the imbalance becomes critical, the result is exertional angina, shortness of breath, or fainting — the classic triad of aortic stenosis.

Diagnosis

A harsh systolic murmur radiating to the neck is the clinical hallmark.

Echocardiography confirms the diagnosis and measures severity.

Exercise intolerance and chest pain in older adults often point to this mechanical problem rather than coronary disease.

Treatment

Once symptoms appear, the prognosis without valve replacement is poor.

Modern therapy offers two options:

-

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)

-

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for patients at higher surgical risk.

Blood pressure control and rhythm management are essential while awaiting intervention.

Key takeaway

Aortic stenosis is a mechanical cause of angina — the heart is strong, but trapped behind a narrow exit. Valve replacement restores not only flow but freedom.

Pulmonary Causes – Lung Conditions Causing Chest Pain

7. Pulmonary Embolism

Sometimes chest pain arrives with a gasp.

The patient stops mid-sentence, eyes wide, unable to draw a full breath. It’s sudden, sharp, and worse with every attempt to inhale.

This is pulmonary embolism (PE) — a blood clot that travels from the deep veins, through the right heart, and lodges in the arteries of the lungs. The result: air without blood, breath without oxygen.

Pain is typically pleuritic (worse with inspiration), and shortness of breath dominates. Some patients cough, others faint. Occasionally, it masquerades as anxiety — until the pulse quickens and oxygen falls.

Diagnosis depends on suspicion. Clues include recent travel, surgery, immobility, or leg swelling.

A D-dimer test may help exclude it; CT pulmonary angiography confirms it.

Treatment begins with anticoagulation — blood thinners to prevent further clots. In severe cases, thrombolysis or catheter therapy restores flow.

Key takeaway: Pulmonary embolism hides behind many masks. When breathlessness and sharp chest pain appear together, think PE — and act quickly.

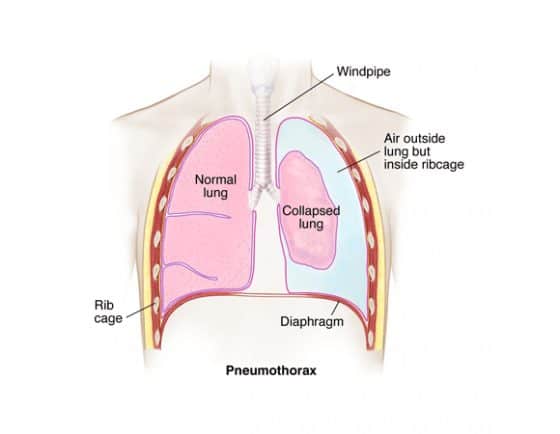

8. Pneumothorax

A sudden “pop,” a stabbing pain, and the feeling that one lung has simply stopped working — that’s pneumothorax.

It occurs when air leaks into the space between the lung and chest wall, causing the lung to collapse partially or completely. Sometimes it follows trauma or a medical procedure. Other times it strikes out of nowhere — especially in tall, thin young men, or in patients with underlying lung disease.

Pain is sudden, one-sided, and pleuritic. Breathing worsens it. A large pneumothorax may cause visible distress and low oxygen levels.

Diagnosis is usually made with a simple chest X-ray.

Treatment depends on size: small ones often resolve spontaneously; larger ones need drainage through a small chest tube.

Key takeaway: If the pain is sudden, sharp, and accompanied by breathlessness — especially after injury or exertion — suspect a collapsed lung.

9. Pneumonia, Asthma, and Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (COPD)

Not every breathless chest hides catastrophe. Sometimes, it’s infection or inflammation speaking.

Pneumonia causes pain that worsens with breathing — the pleura inflamed, the lungs heavy with infection. Fever, chills, and a productive cough tell the story.

In asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the discomfort is more of a tightness — a band across the chest as airways narrow and air becomes trapped. The pain is rarely sharp but often exhausting.

Treatment restores rhythm to the breath: antibiotics for pneumonia, inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids for airway disease, oxygen for those in distress.

Key takeaway: Chest pain from the lungs is often tied to breath — worse on inhalation, eased with stillness — and accompanied by clues the heart rarely gives: cough, fever, or wheeze.

10. Pleuritis (Pleurisy)

Pleuritis — inflammation of the lining around the lungs — can make every breath feel like a knife.

The pain is sharp, well-localized, and worsens with deep inspiration.

Most cases follow a viral infection or pneumonia and resolve within days.

Anti-inflammatory medications ease the pain while nature heals the irritation.

Key takeaway: When chest pain moves with the breath and disappears with recovery, the lungs were simply asking for rest.

11. Lung Cancer

Sometimes chest pain whispers for months before anyone listens.

In lung cancer, the pain is often dull, persistent, and confined to one side — especially when the tumor presses on the pleura or chest wall.

Other signs — a chronic cough, fatigue, unexplained weight loss, or coughing blood — complete the pattern.

Modern screening with low-dose CT scans now detects early-stage cancers in high-risk individuals, especially long-term smokers.

Key takeaway: Persistent, localized pain that refuses to fade deserves attention. Not all chronic pain is benign.

12. Pulmonary Hypertension

Some forms of chest pain don’t come from blockage but from pressure.

In pulmonary hypertension, the arteries that carry blood from the heart to the lungs become narrowed and stiff. The right ventricle must push harder, and over time it weakens.

Symptoms develop slowly — breathlessness, fatigue, faintness, sometimes a dull ache with exertion. Diagnosis relies on echocardiography and, when needed, right-heart catheterization.

Modern therapies — drugs that relax pulmonary vessels or enhance nitric oxide signaling — can improve both survival and quality of life.

Key takeaway: When ordinary effort feels uphill and the heart seems to strain against unseen resistance, think pressure — not plaque.

Gastrointestinal Causes – Digestive Disorders Causing Chest Pain

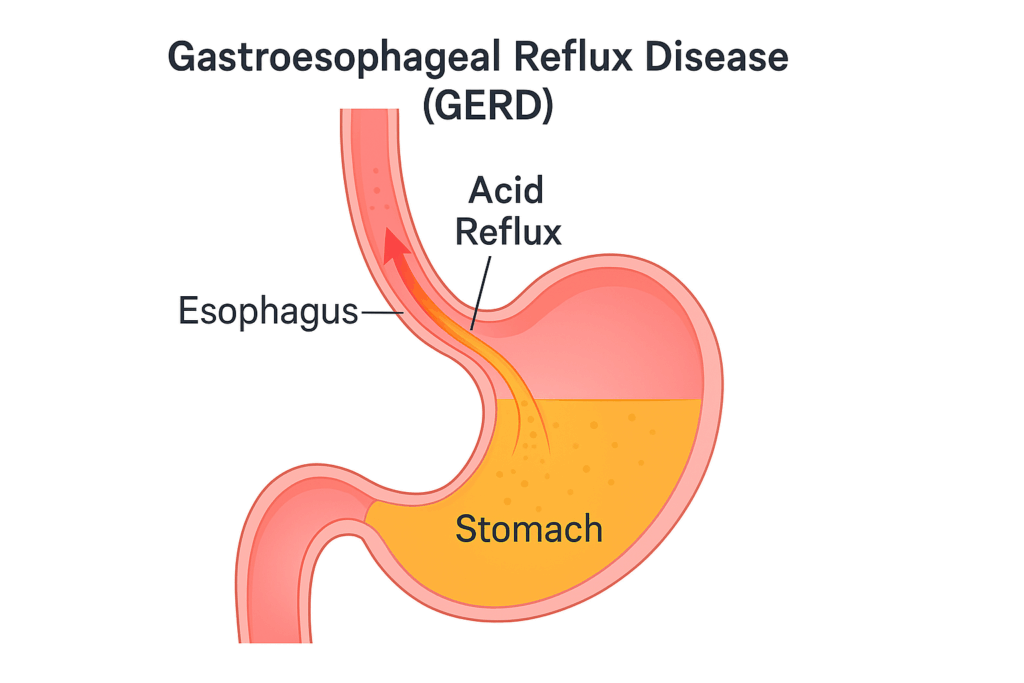

13. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Heartburn has an ironic name. It feels cardiac, but it isn’t.

A deep burning behind the breastbone, rising after meals or when lying down — it’s one of the most common sources of chest pain mistaken for heart trouble.

GERD occurs when stomach acid escapes upward into the esophagus through a weak lower sphincter. The acid irritates the delicate lining, causing a burning or squeezing pain that can radiate to the throat, neck, or back.

Symptoms worsen after eating, with alcohol, caffeine, or late-night meals, and often ease with antacids or standing upright.

Diagnosis is clinical but may involve endoscopy or pH monitoring when symptoms persist.

Treatment begins with simple measures: smaller meals, weight loss, raising the head of the bed. Proton pump inhibitors and H₂ blockers usually bring relief.

Key takeaway: Heartburn can imitate angina so closely that even doctors hesitate. When pain climbs the chest after eating, the stomach — not the heart — may be to blame.

14. Hiatal Hernia

Sometimes the problem isn’t acid but anatomy.

In a hiatal hernia, part of the stomach slides upward through the diaphragm, carrying acid with it. The symptoms mimic reflux — burning, fullness, regurgitation — but stem from a structural shift, not just a chemical one.

Small hernias are common and often harmless. Larger ones may cause persistent reflux or difficulty swallowing.

Diagnosis is confirmed by endoscopy or barium swallow, and surgical repair is reserved for severe or complicated cases.

Key takeaway: Not all reflux is chemical. Sometimes the stomach simply drifts where it doesn’t belong.

15. Esophagitis and Esophageal Spasm

The esophagus is not just a tube — it’s a muscle, and like any muscle, it can inflame or cramp.

Esophagitis occurs when acid repeatedly injures the esophageal lining, leading to burning pain and, at times, bleeding.

Esophageal spasm, on the other hand, causes intense, sudden chest pain that can mimic a heart attack. The esophagus contracts powerfully but ineffectively, creating a deep ache or pressure that may radiate to the jaw or back.

Diagnosis often requires endoscopy or esophageal manometry to measure muscular contractions.

Treatment may include smooth muscle relaxants (nitrates, calcium-channel blockers) and lifestyle changes similar to GERD.

Key takeaway: The chest holds more than the heart. When the esophagus rebels, the pain can be just as dramatic — and just as frightening.

Musculoskeletal Causes – The Chest Wall and Beyond

The term musculoskeletal is used to describe pain associated with muscles, ligaments, bones, and tendons.

16. Musculoskeletal Chest Pain (Costochondritis)

Not all chest pain comes from deep within. Sometimes, it’s right under the fingertips.

In costochondritis, inflammation develops where the ribs join the breastbone. The pain is sharp, localized, and reproducible — pressing on the spot brings it back exactly. That alone distinguishes it from most cardiac causes.

It often follows heavy lifting, coughing, or twisting, and may last for days or weeks.

A physical exam — not a blood test — makes the diagnosis.

Treatment is simple: rest, heat, and anti-inflammatory medication.

The hardest part, often, is the fear that it’s something worse.

Key takeaway: If pressing on the chest recreates the pain, the problem is probably mechanical, not cardiac. Reassurance is sometimes the best medicine.

17. Tietze’s Syndrome

A rarer cousin of costochondritis, Tietze’s syndrome also affects the cartilage where the ribs meet the breastbone — but here, the swelling is visible.

A small, tender lump appears over the joint, warm and sore to touch.

The pain can mimic angina, sometimes radiating to the arm or shoulder, but it is benign and self-limiting.

Rest and anti-inflammatories help, and the swelling fades slowly over weeks.

Key takeaway: A tender, swollen bump on the chest may look alarming — but unlike the heart, it always heals.

Psychiatric Causes – When the Mind Speaks Through the Chest

18. Anxiety Chest Pain and Panic Disorder

Chest pain is the language of fear.

For some, it arrives with no warning — a sudden tightness, a racing heart, a sense that the room has tilted. They clutch their chest, convinced it’s a heart attack.

But the ECG is normal, the troponin is fine, and still, the feeling was real.

In panic disorder, adrenaline surges for no physical reason, tightening muscles, accelerating the heart, and changing breathing patterns. Hyperventilation drops blood CO₂, causing tingling, dizziness, and more fear — a feedback loop of physiology and emotion.

Anxiety-related chest pain is often sharp, fleeting, and unrelated to exertion, but it can be indistinguishable from cardiac pain in the moment. That’s why reassurance matters — and also why recognition matters even more.

Treatment combines therapy, breathing control, and, when needed, medication. Once understood, the attacks lose much of their power.

Key takeaway: Panic may feel cardiac, but it isn’t imagined. It’s the body’s alarm misfiring — loud, convincing, but ultimately harmless.

Other Causes of Chest Pain

19. Drug-Related Chest Pain

Some substances provoke the heart into chaos.

Cocaine, amphetamines, and even high doses of energy drinks can constrict coronary arteries, causing spasm, irregular rhythm, and true heart attacks in healthy young adults.

Any chest pain following stimulant use is an emergency.

Key takeaway: When chemistry replaces calm, the heart can become its first casualty.

20. Herpes Zoster

Sometimes chest pain comes before the rash.

A burning, tingling ache follows the path of a nerve — one-sided, persistent, hard to explain. Days later, a stripe of blisters appears: herpes zoster, or shingles.

The pain can be intense, even before the skin changes appear.

Early antiviral therapy shortens the course and reduces the risk of lingering nerve pain, known as postherpetic neuralgia.

Key takeaway: Not every chest pain is deep. Some begin in the nerves that wrap around the body — a reminder that the skin, too, can hurt from within.

Coda – The Resolution

Chest pain is not a diagnosis. It is a language — one symptom spoken by many organs.

The heart, lungs, esophagus, muscles, and even the mind each have their way of crying out.

For physicians, the task is interpretation: to listen, to translate, to decide who needs reassurance and who needs rescue.

For patients, it’s to remember that not every pain is a warning, but none should be ignored.

Behind every heartbeat is a story. Behind every pain, a question waiting to be answered.

References

- Rui P, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 Emergency Department Summary Tables. National Center for Health Statistics; 2020.

- Malik MA, Alam Khan S, Safdar S, Taseer IU. Chest pain as a presenting complaint in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29(2):565–8. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.292.3241

- Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, Simel DL. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? The rational clinical examination. JAMA. 1998;280(14):1256–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.14.1256

- Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease. Circulation. 2023;148(13):e272–e391. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001178

- Dababneh E, Siddique MS. Pericarditis. [Updated 2025 Jul 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431089/

- Ahmad SA, Khalid N, Ibrahim MA. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. [Updated 2023 May 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430798/

- Levy D, Sharma S, Farci F, et al. Aortic dissection. [Updated 2024 Oct 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441963/

- Goldhaber SZ. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Circulation. 2002;106(12):1436–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000031167.64088.F6

- Kuipers S, Cannegieter SC, Middeldorp S, Robyn L, Büller HR, Rosendaal FR. Travel and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Intern Med. 2007;262(6):615–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01862.x

- Gurung I, Ghassemzadeh S. Spontaneous pneumothorax. [Updated 2025 Jul 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459302/

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Pleurisy. Mayo Clinic. Updated May 3, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pleurisy/symptoms-causes/syc-20351863

- MD Anderson Cancer Center. Lung cancer symptoms. MD Anderson Cancer Center. Updated August 6, 2024. https://www.mdanderson.org/cancer-types/lung-cancer/lung-cancer-symptoms.html

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Pulmonary hypertension. National Institutes of Health. Updated July 18, 2024. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pulmonary-hypertension

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):27–56. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Panic disorder: When fear overwhelms. National Institutes of Health. Updated 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/panic-disorder-when-fear-overwhelms

- Pergolizzi JV Jr, Magnusson P, LeQuang JAK, Breve F, Varrassi G. Cocaine and cardiotoxicity: A literature review. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14594. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14594

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Signs and symptoms of shingles (herpes zoster). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated July 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/signs-symptoms/index.html

Thank you! This is quite helpful.