Estimated reading time: 16 minutes

A young life, unraveled by a rare reaction to a common drug — and what it reveals about statins, mitochondria, and the quiet risks medicine often overlooks.

Christopher Wunsch was 29 — healthy, ambitious, and thriving in a career he loved. As a critical care nurse, he knew the stakes of cardiovascular disease. So when his father suffered a major heart attack and needed bypass surgery, Christopher did what seemed wise: he started taking a statin to lower his cholesterol.

What followed was not expected. Not by him, not by his doctors, and certainly not by the system that told him this drug was safe.

Statins have revolutionized cardiology. In people with known heart disease, after heart attacks, stents, or strokes, they reduce risk and save lives. That’s not up for debate. But when statins are used for primary prevention — in people with no history of cardiovascular events — the balance shifts. The benefits become smaller. The margin for harm grows wider.

And when millions of people take a medication, even rare side effects stop being rare in absolute terms. They become numbers. They become stories. They become lives changed — or sometimes, derailed.

As doctors, this is our dilemma. We want patients who genuinely benefit from statins to stay on them. We don’t want fear to rob people of protection. But we also owe it to our patients to speak honestly about risk, even if that risk is rare, even if it complicates the narrative.

The story you’re about to read is not typical. But that’s precisely why it matters, because behind every clinical trial and guideline is a person, with a body, a history, and a life. And sometimes, the exception is what reminds us how medicine really works.

The Statin That Changed Everything

Before the prescription, there was a life in motion — sharp, determined, and full of promise.

In 1988, during a physical exam before entering nursing school, his cholesterol was flagged as elevated. He was 19 years old, with no significant medical history. He began his nursing career in 1991, starting in medical-surgical units before finding his true calling three years later in critical care.

Christopher thrived as a high-functioning ICU nurse, known for his competence, compassion, and calm under pressure. He had plans to go even further — to become a Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA), a long-held dream. Outside the hospital, he remained active through martial arts, fishing, and outdoor pursuits. He was, by all measures, ambitious and deeply engaged with the world around him — active, vibrant, and outwardly well.

The decision to start Lipitor came swiftly. Christopher was young, active, and seemingly healthy, but with a total cholesterol of 290 mg/dl (7.5 mmol/L) and a strong family history, his doctor suggested a statin. Given his role in the ICU and his trust in medical protocols, Christopher didn’t hesitate. He began 10 mg of Lipitor, just as countless others had.

“I thought I knew everything about these drugs,” he said. “I was a nurse. I trusted the evidence. But I’d only been taught what the pharmaceutical reps wanted us to know.”

He began Lipitor without incident. At least, that’s how it seemed — until months later, when the first symptoms started to surface.

The Descent

It started with episodes of sleep paralysis — terrifying and unexplained. Christopher had never experienced anything like it. He would wake in the middle of the night, conscious but frozen, unable to move his limbs or speak. These episodes became chronic and severe. He feared he was having a stroke.

In time, other symptoms followed: relentless headaches, profound fatigue, and a fog that crept into his thoughts. He often slept up to 18 hours a day, unable to get out of bed. On some days, the exhaustion was so overwhelming that he called in sick to his job as a nurse—something he had rarely done before.

His behavior became increasingly erratic. His wife Anne found herself witnessing a frightening transformation. One night, at 3 a.m., Anne woke to find him digging through the kitchen trash. “I’m looking for milk,” he told her. They didn’t keep milk in the garbage. Another night, she found the front door ajar and Christopher wandering down the street in his underwear. When she called to him, he didn’t respond. When she reached him, he didn’t recognize her.

They went to the emergency room. The evaluation included basic laboratory tests and a neurological examination, all of which were within normal limits. No imaging was performed. The doctors found nothing alarming and diagnosed an atypical migraine, prescribing Imitrex. Anne pushed for imaging, but it was deemed unnecessary.

Worried and frustrated, Anne called her sister-in-law, a nurse, who encouraged her to phone Christopher’s primary care physician directly. He agreed to order an MRI of the brain. The results were revealing, but it would be weeks before anyone followed up on them.

By the time Christopher was hospitalized at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, his deterioration was complete. He couldn’t walk, feed himself, or recognize Anne, their son, or his parents. He was incontinent and nonverbal. He described himself as having become like “a 90-year-old man with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease.”

An MRI revealed innumerable lesions scattered across his brain, including the corpus callosum and brainstem.

A brain biopsy confirmed widespread neuronal apoptosis. Electron microscopy revealed mitochondrial abnormalities: disarrayed cristae, swollen organelles, and dense vacuolization.

🔬 Brain Biopsy Findings

There is one focal area having vacuolization of both neuropil and neuronal cytoplasm. Some of the vacuolization is perivascular. Rare small meningeal and one cortical vessel show lymphocyte cuffing. Vessels show intraluminal fibrinoid deposits…

Electron micrographs show abnormal mitochondria in oligodendroglia and in cells of the vascular wall — either smooth muscle and/or endothelia. The abnormal mitochondria have thickened, disarrayed cristae and inclusions of lysosomal and autophagic vacuoles…

FINAL DIAGNOSIS: LIGHT AND ELECTRON MICROSCOPY:

- 1) Right Frontal Cortex: Spongiform encephalopathy, focal, with abnormal mitochondria (EM)

- 2) Right Frontal Meninges: No pathologic changes

COMMENT: The changes seen by light and electron microscopy are most consistent with a mitochondrial encephalopathy such as MELAS syndrome.

The diagnosis was sobering: a mitochondrial encephalopathy, most consistent with MELAS — a condition he had once read about in passing but never imagined he’d face personally. For Christopher, a nurse who had cared for patients with dignity and vigilance, the realization that he was now the patient, confused, silent, and profoundly vulnerable, struck with deep emotional force. But then, something shifted.

Within 24 hours of starting a mitochondrial cocktail — a blend of vitamins, amino acids, and Coenzyme Q10 — Christopher asked to use the restroom. It was the first coherent sentence he’d spoken in weeks. He recognized Anne. He began to respond.

He wasn’t cured. But he was returning.

Weeks later, though still weak, he was discharged — alive, alert, and beginning to hope. That hope soon turned to determination, as Christopher started seeking answers that would eventually lead him to a groundbreaking research study — and a phone call that would change everything.

🔋 What Are Mitochondria?

Mitochria are tiny organelles inside our cells, often called the cell’s “power plants.” They generate the energy (ATP) that powers nearly every biological function — from muscle contraction to brain activity. They also help regulate calcium levels, cell death, and immune responses. When mitochondria fail, the consequences ripple across the entire body.

🧬 What Is MELAS Syndrome?

MELAS (Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy, Lactic Acidosis, and Stroke-like episodes) is a maternally inherited mitochondrial disorder, most commonly caused by the mtDNA A3243G mutation.

It presents with recurrent stroke-like episodes, seizures, myopathy, lactic acidosis, and progressive neurocognitive decline. Diagnosis involves genetic testing and confirmation by biopsy showing abnormal mitochondria.

The UCSD Call

A few weeks after Christopher returned home, still in recovery, he and Anne happened to watch an interview on Good Morning America. The guest was Dr. Beatrice Golomb, principal investigator of the UCSD Statin Effects Study. She was discussing unusual side effects reported by statin users — symptoms that echoed much of what Christopher had just lived through.

Anne turned to him and said, “You need to enroll.“

Christopher hesitated. “I’m an RN,” he said. “It’s my job to know what I’m giving to patients. And there’s no way the Lipitor I took caused all this.”

But out of respect for Anne — and a lingering sense that something wasn’t adding up — he agreed. He contacted the study team and had his medical records forwarded to them.

Months later, the phone rang. It was Dr. Golomb.

She told Christopher that he wasn’t alone. Several other patients in the study had experienced similar symptoms, including cognitive decline, muscle damage, and profound fatigue. Their brain and muscle biopsies looked nearly identical to his.

Golomb had referred their cases to Dr. Doug Wallace, a world-renowned mitochondrial geneticist at the University of California, Irvine. Wallace reviewed the findings and offered a sobering conclusion: Christopher likely had a mitochondrial DNA mutation that had been dormant — until Lipitor triggered a cascade.

“The statin,” Wallace believed, “opened the gates.”

The call was both validating and devastating. Christopher had spent years questioning himself. Now he had answers — but no easy solutions.

🔬 The UCSD Statin Effects Study

Led by Dr. Beatrice Golomb at the University of California, San Diego, the UCSD Statin Effects Study was one of the first large-scale efforts to systematically investigate the side effects of statins — not just the obvious ones, but the subtle, often-dismissed symptoms patients reported: fatigue, memory loss, muscle pain, cognitive fog.

Unlike traditional trials, which often exclude patients who don’t tolerate treatment, this study aimed to listen to those who struggled. It gathered detailed surveys, medical records, and in some cases, tissue samples to explore possible mechanisms of harm.

For patients like Christopher, it offered something that had been missing from the broader conversation: scientific validation that rare, serious side effects were real and warranted further investigation.

Life After Lipitor

Rehabilitation was long and exhausting. Christopher worked with speech therapists, physical therapists, and neuropsychologists. For months, his goal was simple: to regain a sliver of his former self. He wanted to walk again without assistance. To hold a conversation. To remember his son’s name without searching for it.

Eventually, he returned to work, cautiously optimistic, grateful to be alive. He took a position as a workers’ compensation case manager at American Family Insurance. But it didn’t last.

Tasks that once took him hours now took days. He struggled to retain information, follow sequences, and complete forms that he had once mastered blindfolded. One day, his supervisor entered his office in tears. “What used to take you an afternoon,” she said, “is now taking more than a week.”

She wasn’t being cruel. She was being honest. The work was no longer compatible with his cognitive abilities. Christopher packed up his desk and went home.

That moment marked a different kind of collapse — not neurological, but existential. He was 34 years old. He had worked since he was 12. And now, for the first time in his life, he was out of work.

He spiraled. The depression was deep and unfamiliar. He thought of the patients he had treated over the years — the ones he’d handed Lipitor prescriptions to without a second thought. He wondered: had any of them gone through what he had? Had anyone listened?

At one point, Christopher came close to ending his life. But Anne convinced him to see a therapist. That decision — and the love that led to it — saved him.

Despite everything he had lost, Christopher held on to one thing: the instinct to care. Some days, he wrote down notes from the medical literature, trying to make sense of what had happened. He missed nursing deeply, but even in silence, he found purpose. “I’m still a nurse,” he would say, “even if I don’t clock in.” Over time, that resilience became his compass, not toward a cure, but toward meaning.

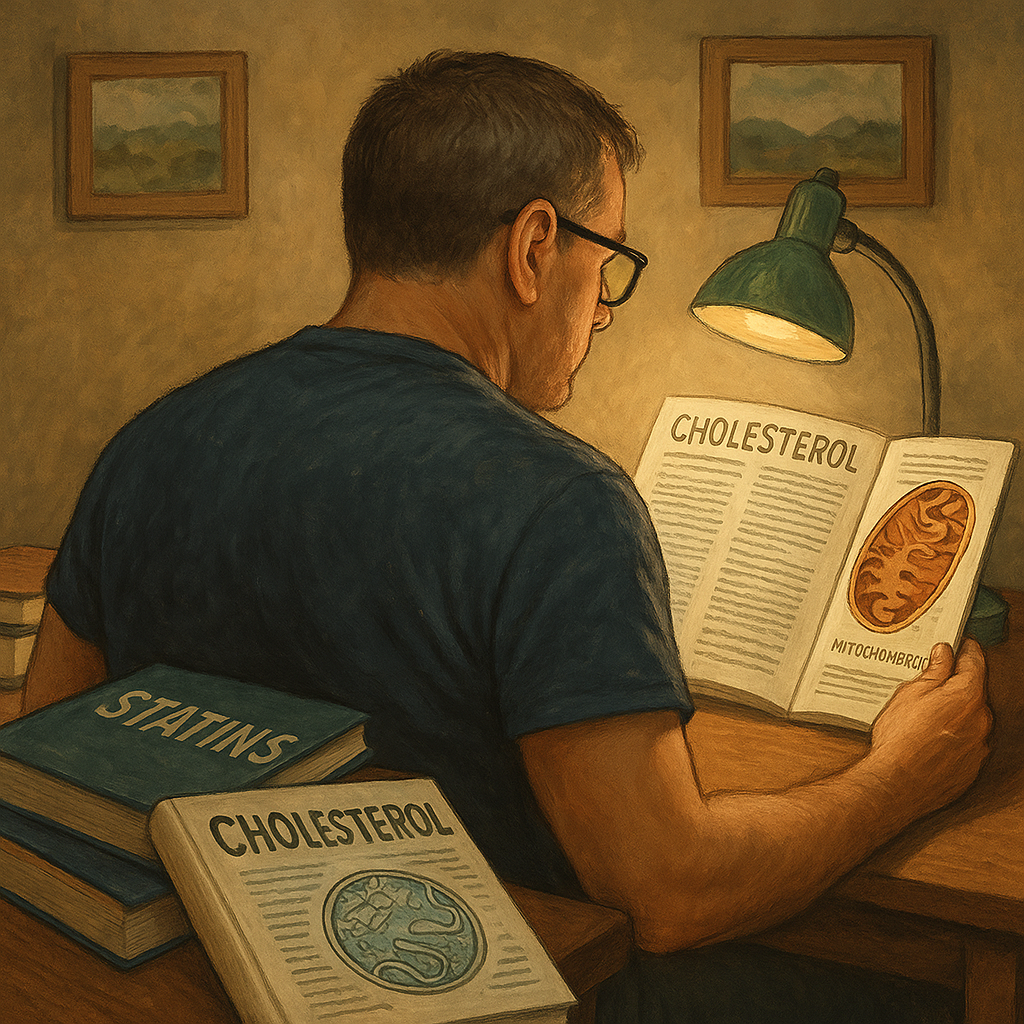

Today, he lives with persistent muscle pain, peripheral neuropathy, and memory deficits that limit his daily functioning. But he wakes each day with gratitude — and with purpose. He devotes his energy to learning everything about cholesterol, statins, and the real-world consequences of treatment decisions. He speaks. He writes. He educates.

He is still, in every way that matters, a nurse.

If you enjoy DocsOpinion’s longform articles, you may also like my Substack newsletter — shorter reflections, serialized essays, and behind-the-scenes notes on medicine, history, and science.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Statins, MELAS, and Mitochondrial Vulnerability

Christopher’s recovery was partial, but his sense of purpose was clear. No longer able to practice as a nurse, he turned his energy inward — reading obsessively, hunting for clues. He devoured scientific literature on cholesterol metabolism, statin pharmacology, and mitochondrial biology. In the process, he discovered something unsettling: his experience wasn’t isolated. And neither was the science.

Although the vast majority of patients tolerate statins without serious issues, emerging studies have shown how these drugs may adversely affect individuals with latent mitochondrial vulnerabilities, including those with conditions like MELAS.

MELAS is a rare disorder caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA. It primarily affects tissues with high energy demand, such as the brain and muscles, and often presents with symptoms like seizures, cognitive decline, lactic acidosis, or stroke-like episodes. In Christopher’s case, the features were subtle at first, but they progressed quickly and dramatically.

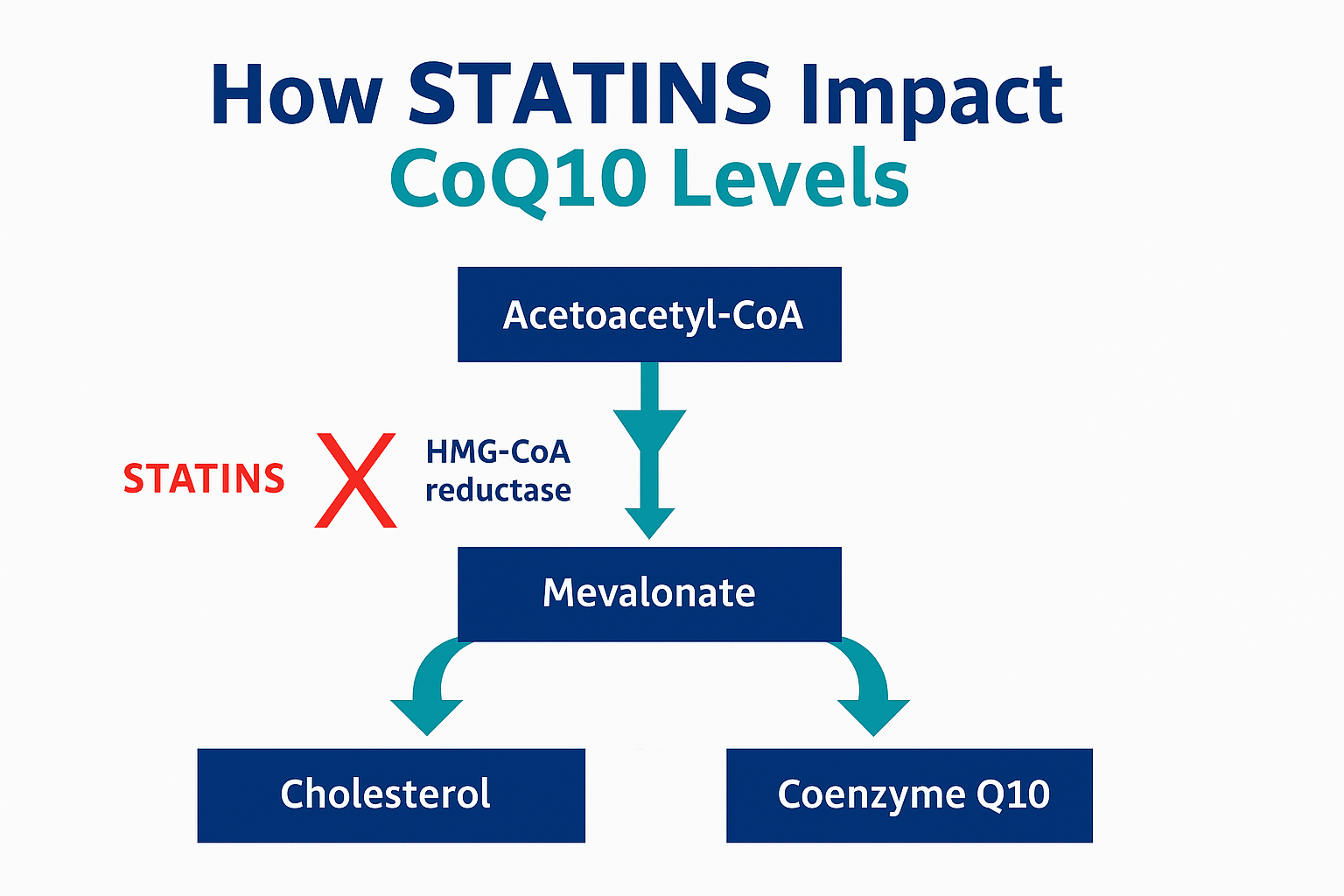

Statins lower cholesterol by blocking the mevalonate pathway. However, that pathway also produces Coenzyme Q10, an essential component in mitochondrial ATP production.

In patients with latent mitochondrial disorders like MELAS, mevalonate pathway suppression can tip a delicate balance. ATP production falls. Oxidative stress rises. In tissues with high energy demands, such as the brain and muscle, the consequences can be catastrophic.

This was a turning point for Christopher: “One hundred percent of my goal is to make people aware that mevalonate blockade is not without potentially devastating risks,” he told me. “Dr. Beatrice Golomb once said statins offer less than a 1% absolute risk reduction — and may have side effects in up to 20% of users.”

Statin-induced suppression of CoQ10 can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, impairing energy production, increasing oxidative stress, and disrupting calcium balance. In patients like Christopher, this can unmask or accelerate previously silent mitochondrial pathology.

This mechanism may also help explain his dramatic response to mitochondrial support therapy. By replenishing Coenzyme Q10, his cells may have partially recovered their ability to produce energy and stabilize critical cellular processes.

One notable example comes from a 2024 study by Ryan and colleagues, who demonstrated that high-dose atorvastatin (80 mg/day) significantly reduced skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration after just eight weeks in overweight but otherwise healthy individuals.

The decline in oxidative phosphorylation capacity exceeded 30% — a striking finding that confirmed statins can directly impair mitochondrial energetics, even in people without prior mitochondrial disease. This raises legitimate concern for those with latent or inherited mitochondrial vulnerabilities.

These adverse effects remain rare, but their symptoms — brain fog, fatigue, muscle pain — are common and nonspecific. That makes them easy to overlook. Several published cases report significant improvement after discontinuing statins and initiating mitochondrial support therapy.

This isn’t an argument against statins. It’s an argument for precision. For thinking beyond averages. For recognizing that even widely beneficial therapies carry trade-offs, and those trade-offs matter most when they show up in your patient’s life, not just in the margins of a clinical trial.

How We Talk About Risk Matters

Christopher Wunsch’s story is rare. But his perspective raises questions that are anything but.

As clinicians, we’re taught to practice evidence-based medicine. We cite landmark trials, calculate risk scores, and prescribe with guidelines in mind. Statins have transformed outcomes for patients with established atherosclerotic disease, of that there’s no serious debate. But the conversation becomes more nuanced in primary prevention, where the benefits are smaller and the risks feel more personal.

Christopher has spent more than two decades not just healing, but learning. He’s read the literature that most patients never see. And he’s questioned the assumptions that many of us were taught — not with hostility, but with the clarity of someone who paid the price.

And therein lies the issue. Too often, we rely on relative risk reductions that sound impressive but mask the modest absolute benefits in low-risk populations. Too often, the conversation around statins is framed in binary terms — take it or don’t — when the reality is far more individualized.

This isn’t about abandoning statins. It’s about acknowledging that even powerful therapies come with trade-offs. Those side effects, while rare, are real. And that patients deserve transparency, not just about what a drug can do, but also about what it might cost.

Stories like Christopher’s challenge us to re-examine not just our evidence base, but the way we communicate it. They remind us that population-level benefit doesn’t always align with individual-level experience — and that medicine, at its best, remains a dialogue, not a directive.

To my fellow statin prescribers:

When you’re treating someone for primary prevention, pause. Don’t just ask “Does this patient qualify?” Ask, “Will this truly help them?” Will years of statin therapy likely reduce their risk in a meaningful way? Or are we prescribing more out of habit than conviction?

Don’t default to treatment just to err on the side of doing something. Prescribe because you’re confident the benefit outweighs the burden, for that individual, not just for the population. That’s the responsibility —and the privilege —of personalized care.

A Note of Gratitude

My sincere thanks to Christopher Wunsch for generously sharing his experience — not only the clinical facts, but the personal pain, uncertainty, and hard-earned insight that followed. His courage, resilience, and commitment to educating others exemplify what it means to turn adversity into advocacy. This article would not exist without his story, and his mission continues to make a difference.

I’m also profoundly grateful to my dear friend, Dr. Barbara Roberts, MD, for bringing Christopher’s story to my attention and connecting us. Her unwavering dedication to challenging assumptions and keeping critical conversations alive has helped shine light where it matters most.

Sources & Further Reading

-

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Statins for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

- Mancini GBJ, Ryomoto A, Yeoh E, Iatan I, Brunham LR, Hegele RA. Reappraisal of statin primary prevention trials: implications for identification of the statin-eligible primary prevention patient. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025 Feb 25:zwaf048. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwaf048. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39998386

- Thomas JE, Lee N, Thompson PD. Statins provoking MELAS syndrome. A case report. Eur Neurol. 2007;57(4):232-5. doi: 10.1159/000101287. Epub 2007 Mar 26. doi.org/10.1159/000101287

- Ramachandran R, Wierzbicki AS. Statins, Muscle Disease and Mitochondria. J Clin Med. 2017 Jul 25;6(8):75. doi: 10.3390/jcm6080075. PMID: 28757597; PMCID: PMC5575577.

- Ryan TE, Torres MJ, Lin CT, Clark AH, Brophy PM, Smith CA, Smith CD, Morris EM, Thyfault JP, Neufer PD. High-dose atorvastatin therapy progressively decreases skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity in humans. JCI Insight. 2024 Feb 22;9(4):e174125. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.174125. PMID: 38385748; PMCID: PMC10967389.

- Taylor BA, Thompson PD. Muscle-related side-effects of statins: from mechanisms to evidence-based solutions. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2015 Jun;26(3):221-7. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000174. PMID: 25943841.

- Finsterer J, Segall L. Drugs interfering with mitochondrial disorders. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2010 Apr;33(2):138-51. doi: 10.3109/01480540903207076. PMID: 19839725.

- Golomb BA, Evans MA. Statin adverse effects: a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2008;8(6):373–418. doi.org/10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004

- Larsen S, et al. Simvastatin effects on skeletal muscle: relation to decreased mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(1):44–53. doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.036

- Mollazadeh H, Tavana E, Fanni G, Bo S, Banach M, Pirro M, von Haehling S, Jamialahmadi T, Sahebkar A. Effects of statins on mitochondrial pathways. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021 Apr;12(2):237-251. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12654. Epub 2021 Jan 29. PMID: 33511728; PMCID: PMC8061391.

Portions of this article were developed with the assistance of ChatGPT, an AI language model by OpenAI, to help refine structure, language, and clarity while preserving the author’s voice and scientific integrity

I have CAD and in past years I was prescribed 3 different statins to lower my somewhat elevated cholesterol and LDL. Each time I felt like I was 95 years old with absolutely no energy and motivation. I just wanted to sit and literally do nothing all day. The effect was immediate each time and I stopped the statin. I’ve never taken another statin since. I am so grateful for this article and would love to find out more about this subject.

I want to say thank you, Dr Sigurdsson for helping bring to light the all too often dismissal of the very real consequences of Mevalonate Blockade.

Thank you, Chris, for your courage, clarity, and determination to speak the truth. Your story sheds light on what too often remains in the shadows. I’m honored to help bring it forward and grateful for the opportunity to learn from you.

Do you have a website or Substack where you share your research? I would love to see what you are finding regarding cholesterol as a whole and management.

Chris’ story of brain fog and muscle pain resonates with me too after having been put on a preventative dose of simvastatin as a type 2 diabetic, although I never fell to anything like the same depths. A clear CAC scan validated my decision to abandon all statins and thanks to another of Dr Sigurdsson’s blogs, use my Trig/HDL ratio as a proxy for pattern A atherosclerosis risk while reversing my diabetic profile through a ketogenic diet without fear of raised Total Cholesterol. I’m truly grateful for this dissemination of information and hope it spreads far and wide. Thank you.

My husband and I, he 78 and myself 65 have both been total carnivore for 5 years. Our doctor tested our cholesterol 4 years ago and it was way up. Since carnivore we have overcome many ailments and so we are are not scared of high cholesterol. BUT our fats do not come from seed oils they come from meat. We eat red meat and meat fat. We are exceedingly healthy. Our doctor never tested our cholesterol again.

Another science denier making statements.

Sorry, it’s not clear who you regard as the science denier. Can you clarify please?

Acorda

My previous doctor GP. Put me on 20mg statin 12 years after my heart attatack and triple bypass operation ,my GP retired and another GP Took over and he put me upto 80mg astovastatin and said 20mg you might aswell no be on one,so I took them and went down hill slowly,with back ache and fatague ,the new GP moved on ,So I decided to revert back to 20mg by braeking the 80 mg statin in to 4 pieces ,and never looked back ,back pain ceased within a week a bit more active ,but now at 70/71 soon, I know I’m not 21 years old,so I live to my own body and listen to it ,and enjoy what I can, So Statins are Questionable.and a Ps My Blood Tests Don’t Showany Adverse Affects to Them.

What can you recommend to this healthy 78 yr old female with a lifetime of consistent exercise and healthy eating, a 400 calcium heart score done 10 years ago, good to excellent lipid levels until 60s when cholesterol began sneaking up to 210 to 220-30, now taking 5mg. Rosuvastatin at MD insistence, low B/P, NO cardiac symptoms, but LP(a) in 200s. [stop the statin?]

Hi Suasan.

I can’t give personal medical advice, but I can try to share share how I think through a case like this.

At 78, healthy and active, with no cardiac symptoms and good blood pressure, the benefit of continuing a low-dose statin like rosuvastatin is probably modest—especially in primary prevention. Statins reduce cardiovascular events, but the absolute benefit decreases with age, particularly in people doing well otherwise. The calcium score of 400 from 10 years ago shows there is atherosclerosis, but we don’t know if it’s progressed. The elevated Lp(a) is a real risk enhancer, though unfortunately, statins don’t lower Lp(a).

So this becomes a values-based decision: continuing 5mg of rosuvastatin is reasonable if it’s well tolerated, but stopping it is not necessarily wrong either. It’s not likely to be a game changer either way. Best to discuss with your doctor in that context.

Show me the proof that statins prevent CVD?? Real evidence. Reality is there isn’t any. Period. You show Chris’s incredible story yet you are in complete denial about the damage statins do to everyone. So I ask where is the evidence you say is unassailable the good that statins provide?????

Thanks for your comment — I appreciate your passion and your concern.

This article wasn’t written to defend statins as a whole, but to spotlight a rare and serious adverse effect that too often gets ignored. That said, I think it’s important to clarify that the benefits of statins — particularly in people with established cardiovascular disease — are supported by decades of randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses.

Here are just a few key examples:

– LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with

atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med.

2005;352:1425–1435.

– Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of more

intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from

170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–

1681.

– Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin

therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from

28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393:407–415.

– Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary

heart disease:the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet.

1994;344:1383–1389.

– Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N Engl J Med.

1996;335:1001–1009.

– Long-Term Intervention with Pravastin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study

Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in

patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol

levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–1357.

– Karlson BW, Wiklund O, Palmer MK, et al. Variability of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol response with different doses of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin,

and simvastatin: results from VOYAGER. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2016;2:212–217.

– Number needed to treat with statins to prevent one cardiovascular event in 5 years link

– Serruys PW, de Feyter P, Macaya C et al. Fluvastatin for prevention of cardiac events following successful first percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:3215–3222. [PubMed: 12076217]

– Letter 49Statin’s benefit for secondary prevention confirmed link

– Kytö V, Saraste A, Tornio A. Early statin use and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction: A population-based case-control study. Atherosclerosis. 2022 Aug;354:8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.06.1019. Epub 2022 Jun 25. PMID: 35803064.

– Tecson KM, Kluger AY, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Liu B, Coleman CM, Jones LK, Jefferson CR, VanWormer JJ, McCullough PA. Usefulness of Statins as Secondary Prevention Against Recurrent and Terminal Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events. Am J Cardiol. 2022 Aug 1;176:37-42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.04.018. Epub 2022 May 21. PMID: 35606173-

– Naci H, Brugts JJ, Fleurence R, Tsoi B, Toor H, Ades AE. Comparative benefits of statins in the primary and secondary prevention of major coronary events and all-cause mortality: a network meta-analysis of placebo-controlled and active-comparator trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013 Aug;20(4):641-57. doi: 10.1177/2047487313480435. Epub 2013 Feb 27. PMID: 23447425.

– Vale N, Nordmann AJ, Schwartz GG, de Lemos J, Colivicchi F, den Hartog F, Ostadal P, Macin SM, Liem AH, Mills EJ, Bhatnagar N, Bucher HC, Briel M. Statins for acute coronary syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD006870. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006870.pub3

Of course, no drug is without harm — and recognizing that is the heart of this article. My goal isn’t to suggest statins are risk-free, but to emphasize the importance of both scientific evidence and individual patient experience. If you’re interested, I’d be happy to provide a much longer list of references — or continue the discussion in more detail.

If someone has a carotid artery plaque, verified by echocardiogram, is it advisable to take Rosuvastatin? The doctor recommends 20mg. He is 55 years old. Normal lipid profile, LDL 260mg. No metabolic syndrome.

I am grateful Mike wrote and deeply thankful Dr. Sigurdsson responded with this research. I have felt the convincing pull of countering research through the years and happy for this targeted list to provide its own pull.

Susan