Share this post:

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, Holding the Line — Staying Human in Medicine, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

“The physician must learn to bear the wounds of the heart.”

— Ambroise Paré

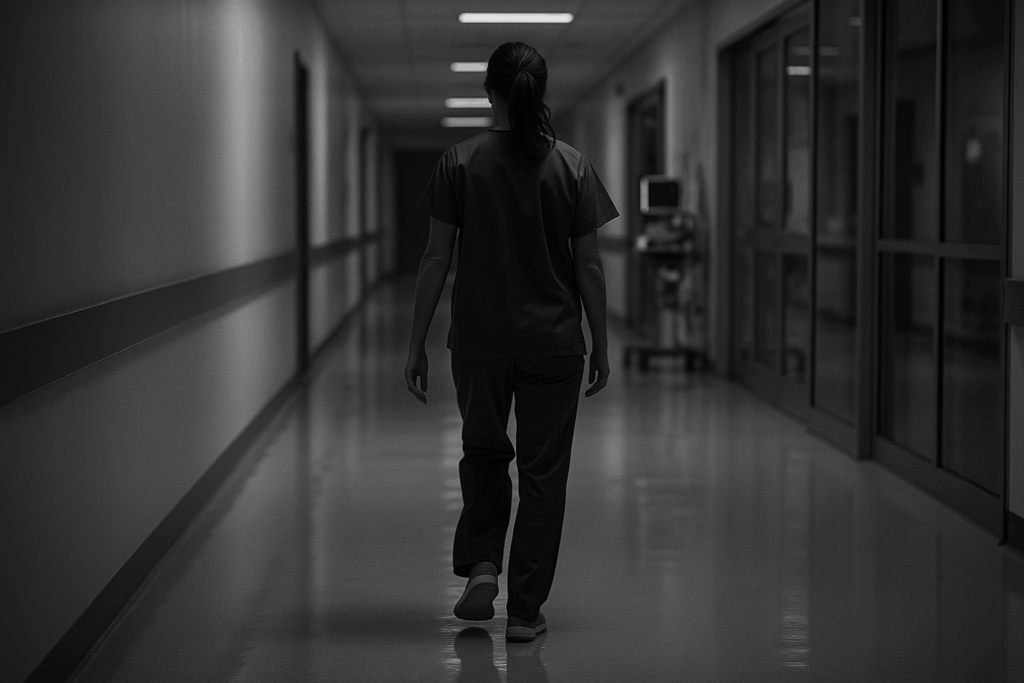

I used to think I could stay untouched by the pain I witnessed. That I could carry grief without absorbing it. That I could walk through medicine without it ever walking through me.

No one practices medicine for long without being marked by it. You don’t feel it happening at first; it settles in quietly, case by case, until one day you realize a part of you has shifted

Every calling has a breaking point. In medicine, it often begins when compassion starts to ache.

It doesn’t happen all at once. It builds imperceptibly, like fatigue mistaken for endurance. You still listen, still care, still nod in the right places. But somewhere inside, a thin crack appears. A quiet thought enters: I can’t keep doing this forever.

You silence it, because medicine—real medicine—runs on compassion. You can teach anatomy and pharmacology, but not the willingness to sit with another person’s suffering. That is the paradox of compassion: the same force that makes healing possible can also hollow out the healer.

We give names to this phenomenon—burnout, emotional fatigue, empathic distress—but the words feel too clean for something that rearranges a person from the inside. The truth is simpler and harder: the suffering of others leaves a mark.

I once believed I could outrun that truth. I thought resilience meant staying untouched. I thought experience would harden me. But medicine teaches otherwise. There are cases that never fully leave you.

The Code

It happened long ago, though for me it could have been yesterday. A quiet summer Sunday, harmless on the surface. Sunlight drifted through the hospital corridors, the world outside warm and ordinary—birds in the trees, children shouting over a football match somewhere in the distance. Nothing in the air hinted at tragedy. And yet it was already on its way.

He was in his twenties—strong, athletic, a new father. He came in with chest discomfort that didn’t sound dangerous. The ECG was ordinary. The troponin barely moved. His numbers looked fine. His face did not. Then, without warning, he went into ventricular fibrillation. One moment he was speaking, the next he was gone.

We shocked him. Once. Twice. Three times. Then—a pulse. Weak, temporary, but enough to move. We rushed him to the cath lab, urgency pounding through the sterile corridors. We needed an explanation: a clot, a dissection, something to fight. But his coronaries were pristine. The angiogram stared back at us, clean and merciless. Nothing to explain. Nothing to fight.

Then the alarms erupted again. Another arrhythmia, faster and more violent. More shocks. More compressions. More epinephrine. The room grew hot with effort and fear. Gloves snapped. Voices tightened. And through it all, an absurd soundtrack: someone’s pager kept chirping a pointless little melody in the corner, indifferent to the fact a man was dying. It made the scene feel obscene—life insisting on ordinariness while death was being negotiated.

Eventually, the rhythm on the monitor dissolved into stillness. It was the kind of silence that tells the truth long before anyone speaks. I stopped the code. No one moved. We stood there for a moment, surrounded by used syringes, discarded packaging, and the terrible knowledge that we had reached the limit of what medicine could do. When effort ends, grief doesn’t walk in—it seeps.

Aftershock

What follows a code like that is its own kind of ghost. No one moves at first. The room doesn’t empty right away. There is no instant cleanup, no efficient transition to the next case. There is just a heavy, peculiar stillness—as if the air has shape and weight. Nobody makes eye contact. Someone steps back from the table slowly, as though ashamed of still being alive. The gloves come off. The aprons drop. Everything smells like adrenaline and sweat and silence. That awful silence.

Then you do the worst part of the job—you go and break someone’s world. His wife was in the waiting room, still holding his phone and a clean T-shirt she had brought from home. She looked up when I walked in. People can read truth before they hear it. Something in her collapsed before I even spoke.

I don’t remember what I said. I only remember her saying, “But he was fine this morning. We had breakfast.”

I drove home that night with the windows down, trying to breathe air that didn’t taste like antiseptic and failure. I didn’t sleep. I don’t think anyone who was there did.

People think moments like that make you harder. They don’t. They make you porous. And once grief seeps through the cracks, you never become fully watertight again.

Corrections

So you learn to protect yourself. Distance enters your practice—not as a decision, but as a survival reflex.

I once cared for an elderly man with advanced heart failure who came to the clinic every month, pulling his oxygen tank behind him. He was unfailingly polite, uncomplaining, gentle in a way the world no longer teaches. I liked him. When he died, I did what doctors do: I spoke to the family, wrote the note, and closed the chart. Then I found myself avoiding patients who reminded me of him. I scrolled faster through lists. I spoke in shorter sentences. I saw symptoms before people.

That is how distance begins—not as indifference, but as self-preservation.

We use words like ‘professional detachment’ as if they represented wisdom. But detachment has a cost. It spares the physician but slowly starves the patient. Something essential is lost—not competence, but connection. The current between human beings weakens.

In time, you begin to understand a different truth: you cannot survive medicine by feeling everything, but you cannot honour it by feeling nothing.

The Line

The tension between empathy and endurance is older than modern medicine. The Stoics warned against emotional contagion—bleeding with others does not heal them. Buddhist teaching speaks of compassion without attachment. Aristotle believed virtue lived not in extremes but in the hard middle—feeling deeply, yet remaining steady.

But philosophy is just theory until tested in a room where a life is breaking.

A woman recovering after a heart attack told me she was tired of doctors trying to make her feel better. She didn’t want comfort. She wanted truth, delivered gently, but without disguise.

“I don’t need you to feel my fear,” she said. “I just need you not to look away from it.”

That sentence became a compass. Compassion is not the transfer of suffering. It is not emotional fusion, not drowning together. It is presence. It is bearing witness without turning away.

When compassion matures, it stops being a feeling. Feelings are weather—unstable, passing. Mature compassion is a discipline. A decision to remain.

You stop trying to carry every burden. You stop confusing intensity with loyalty. You understand that grief cannot be absorbed by another person like water into cloth. Your task is simpler and harder: to stand close to suffering without disappearing inside it.

Healing, I have learned, is not always about treatment. Sometimes it is about not abandoning someone in their darkest hour.

I still think about the young man who died on that summer Sunday. I think of his wife holding that clean T-shirt in the waiting room. I think of the old man with the oxygen tank. Their names live in the corners of my memory — the quiet places that never appear in any record.

Medicine does not teach us what to do with sorrow. It teaches diagnosis, intervention, urgency. It does not teach what to do when effort is exhausted and a room falls silent. It gives us tools, but not peace.

So we carry on. Not untouched, but changed. We hold the line each day between feeling and falling, between being present and being consumed. It is not a line you find once. It must be found again and again.

There is no triumph in this. Only a simple vow: to remain human without breaking.

Some days I manage it. Other days I don’t. But I keep trying—because in a world where everything can be measured except the weight of the human heart, this is the only promise that still feels like medicine.

And on the hardest days, when the sorrow threatens to breach the walls again, I remind myself of something I once heard and never forgot:

The task is not to feel less.

The task is to walk into the room and stay.

Even when it hurts.

Especially then.

This is the work. This is the cost. And still—we choose to stay.

Thank you, Doc — such exceedingly raw and precise words that pierce the heart, mind, and soul, capturing a moment in your time and space.

Beautiful insight into our role as physicians, to remain present and bear witness.

thanks you

bob

Thank you Bob — staying present is the true work, isn’t it?

Really love and enjoy reading your articles Doc.

I am an MD too and can totally relate. Thank you for sharing!

Thank you so much Alex — that means a lot, especially coming from a colleague. I’m glad the piece resonated with you. It’s something we all feel in medicine but rarely pause to put into words.

I never really thought about that before. A good reminder to treat your doctor well, because they’re human and have emotions just like everyone else. It puts the doctor in a tough situation. In school, they learn their trade, which is quite complicated. Like a scientist or an engineer. When they start practicing, a whole new compassion role enters. Like a psychologist or therapist that uses empathy and emotional intelligence. Doctors deserve extra congratulations for combining these two disparate skills.

This is a true parable of compassion. Thank you.

Thanks for reading and sharing your thoughts 🙂

Such a beautiful insightful narrative. ‘The task is not to feel less, the task is to walk into the room and stay.’ Yes, it seems life’s awe-ful raw brutality could sweep us away if we didn’t anchor into our knowledge, practice and one another. Thank you for this piece. I will pass it forward.

Thank you Anamaria — that’s exactly it. We can’t turn off the feeling, only learn to stand inside it together. I’m grateful you read it and passed it on.

I love it when my doctor shares a small piece of her life with me, it makes me remember that she is human too. This is a beautiful essay, I loved reading it.

Thank you — that means a lot. I’ve always believed that a small glimpse of our own humanity can do more for trust than any checklist or protocol. I’m glad the essay resonated with you.