Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, “The Tyranny of the Average: Why Medicine Struggles With the Individual”, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

He sits across from me, his file glowing on the computer screen. Numbers everywhere: cholesterol edging upward, blood pressure leaning north, a family tree littered with cardiac potholes.

He leans forward, eyes narrowing.

“So, doctor—what are my chances?”

I recite the liturgy: statins cut relative risk by about 25%, blood pressure control lowers stroke risk by 30–40%. Add them up, and the curves bend favorably.

He doesn’t look reassured.

“Yes, but will it happen to me—or not?”

There it is. The one question medicine never really answers. We speak in averages, in cohorts, in percentages. Patients live in the singular.

Science thrives on the crowd; life is lived in the first person. That tension—between population truth and individual fate—sits like a stone in the center of modern medicine.

The Man Who Wasn’t There

In 1835, a Belgian astronomer named Adolphe Quetelet got bored of stars and turned his telescope on people. He measured soldiers by the thousands—height, chest size, weight. When he plotted the numbers, a curve bloomed, neat as a garden arch.

At its center was a figure he called l’homme moyen—the “average man.”

Here’s the trick: he didn’t exist. No soldier in Quetelet’s dataset had those exact measurements. The “average man” was a ghost, conjured by arithmetic.

But ghosts, it turns out, can be powerful. Insurers began charging premiums based on him. Governments built census tables on him. Doctors started using him to define who was “normal” and who was not.

Quetelet even gave us another ghost that still haunts clinics today: the body mass index (BMI). A 19th-century astronomer’s equation for comparing soldiers somehow became a global arbiter of health, condemning millions as “overweight” or “obese.”

The same with the Framingham Heart Study. Brilliant in its scope, it provided us with population truths about cholesterol, smoking, and hypertension. However, the Framingham risk score, widely used in clinics, often tells individuals more about their resemblance to a crowd than about their own personal risk.

Medicine never really escaped Quetelet’s shadow. Every trial, every guideline, every target still whispers the same incantation: Here is what happens on average.

But no one is average. Not me. Not you.

And yet the ghost keeps calling the shots.

The Patient in the Denominator

A trial report lands in the New England Journal of Medicine:

“Statins reduce cardiovascular risk by 25%.”

To the statistician, it’s a clean triumph. Randomization held. Confidence intervals tight. The p-value bows politely below 0.05. The curve has shifted, and the drug is blessed.

To the epidemiologist, it’s a dream of scale. They translate percentages into absolute numbers, calculate the number needed to treat, and sketch out how many heart attacks could be avoided if millions took the pill. The view is sweeping, godlike, population-sized.

But then—back in the clinic—a patient sits across from me. One person. Not a curve. Not a cohort. A man with a pillbox and a mortgage. He asks the question none of the graphs answer:

“Will this pill save me?”

Now the math stumbles.

-

If his 10-year baseline risk is 20%, a 25% relative reduction translates to a 5% absolute decrease. Treat 20 people like him, and prevent one heart attack.

-

If his risk is 5%, the same drug results in only a 1% drop. Now it takes 100 people treated to spare one.

Both outcomes are “statistically significant.” Both satisfy the epidemiologist. But significance doesn’t keep you awake at night. Odds do.

For the patient, the story isn’t a smooth bell curve. It’s a coin toss with his face on it.

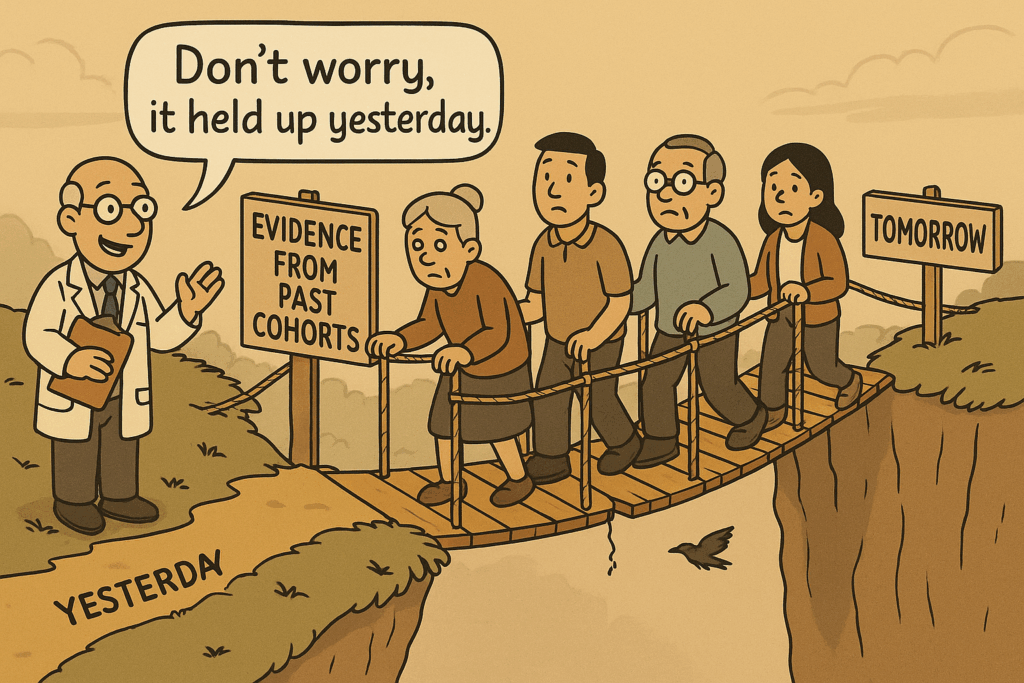

David Hume saw this problem centuries ago. The past, he said, can only suggest, never guarantee, the future. A million sunsets don’t prove the sun will rise tomorrow. Medicine leans on the same fragile bridge: because statins lowered risk yesterday, we assume they will lower it tomorrow. Because blood pressure drugs prevented strokes in one cohort, they must prevent them in the next.

But patients don’t live in cohorts; they live in the unknown tomorrow.

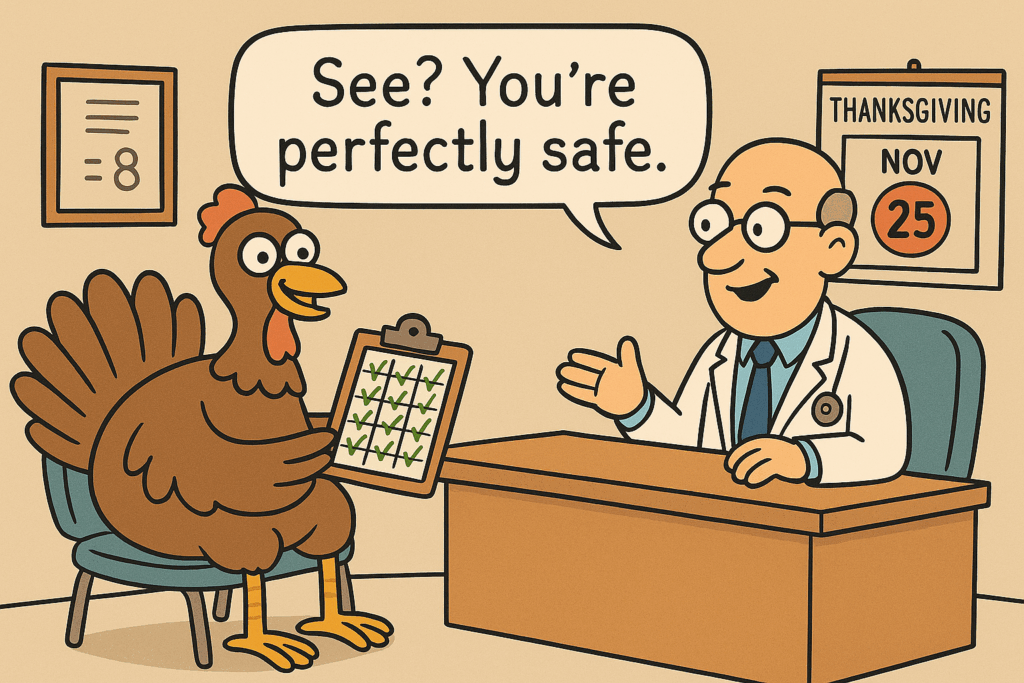

Nassim Taleb sharpened the point with his “Black Swan.” The turkey fed every morning grows confident in its safety — until the day before Thanksgiving. Averages lull us with stability, until a single, unpredictable event topples the curve.

Hume and Taleb never practiced medicine, but their warnings haunt every consultation. The data may say what usually happens. It can never say what will happen to you.

And yet, every consultation pretends otherwise. We quote numbers as though they were fate, wrap uncertainty in percentages, and hope the patient doesn’t notice the sleight of hand.

Of course, they always do.

Drawing Lines on Water

She is 68. Retired teacher, sharp eyes, sharper tongue. Her cholesterol panel has just come back.

Her LDL cholesterol: 71.

The guideline states that the goal is to be under 70.

Her doctor clears his throat and smiles politely. “We’d like to get you just a little lower.”

She leans back in the chair, arms crossed. “So at 71 I’m in danger, and at 69 I’m safe? That’s ridiculous.”

She’s right. Biology doesn’t work in integers. Arteries don’t calcify the moment a molecule tips across a paper line. Plaque doesn’t care what the guideline committee voted in its last meeting.

But medicine loves lines. They make chaos look orderly. They fit neatly into electronic health records. They let policymakers set targets, insurers write contracts, and researchers sort people into “controlled” and “uncontrolled.”

For her, though, the cutoff feels absurd. Two milligrams of cholesterol stand between her and another prescription.

This is not new. Blood pressure thresholds (140/90, now 130/80) have been shifted with the stroke of a pen, instantly reclassifying millions of people as “hypertensives.” The same with diabetes: an A1c of 7.0 earns you a diagnosis, 6.9 spares you—until the next committee revises the boundary.

Philosophically, it’s sleight of hand. The world is a spectrum; we redraw it as categories. Wittgenstein warned that meaning depends on context. A blood pressure of 142 doesn’t mean the same for a frail 85-year-old as it does for a marathon runner. But guidelines flatten both into the same box, as if language were stronger than physiology.

And hidden inside every threshold is an ethical choice. Lowering the LDL target from 100 to 70 wasn’t just a clinical decision; it created millions of new “patients.” It swelled the market for statins and PCSK9 inhibitors. They told people they were sick, even if real-life benefit might be marginal.

The absurdity isn’t lost on her. “I’ve been teaching math for 40 years,” she says, half-smiling. “I know a rounding error when I see one.”

Her doctor chuckles nervously. But the truth is harder: the line isn’t really for her. It’s for the average.

The Promise and the Trap of Precision

Medicine has always aspired to escape the tyranny of the average. If only we could peer deep enough — into the genome, the proteome, the microbiome — the fog of probability would lift and each patient would be revealed in crisp focus.

The dream isn’t entirely fantasy. In oncology, genetic testing already steers treatment: a breast tumor with one mutation gets drug A, with another mutation, drug B. This isn’t population risk; it’s a targeted strike. Precision medicine, they call it.

Cardiology wants the same magic. Polygenic risk scores promise to categorize individuals based on thousands of subtle genetic variations. Maybe we’ll finally know who is doomed to heart disease and who can eat bacon with impunity. Companies already advertise DNA tests as if the future were printed in your saliva.

But here comes the irony: precision medicine still speaks in probabilities.

-

Your polygenic score says you’re in the top quintile for coronary risk. Does that mean a heart attack is certain? No, only that you’re more likely than the crowd.

-

Another person lands in the lowest quintile. Does that guarantee safety? Hardly—a bad lifestyle or sheer bad luck can still topple the odds.

We’ve sliced the population into finer and finer subgroups, but they’re still groups. The individual still stands outside the curve, asking the same question asked at the start: “Will it happen to me?”

Meanwhile, “patient-centered care” tries another route. Instead of narrowing risk with genetics, it reframes the conversation around values: What matters to you? Living longer, or living free of side effects? Numbers bend when measured against life goals.

William Osler once said it was more important to know what kind of patient has a disease than what kind of disease a patient has.

Precision medicine and patient-centered care sound like opposites — one dives inward into the molecule, the other outward into the story — but both circle back to Osler’s point. The numbers alone are never enough.

The genome can tell you your odds of a heart attack. It cannot tell you if you’ll be there to dance at your granddaughter’s wedding.

Beyond the Average

The consultation winds down. Lab results explained, guidelines reviewed, pills debated. He lingers by the door, hand on the knob.

“So what does this really mean for me?”

There it is again — the question that no graph, no curve, no committee can answer.

Medicine has no final reply. The numbers can guide, but they cannot prophesy. That isn’t a flaw in the science. It’s the nature of living one life instead of a thousand.

Karl Popper once wrote that science doesn’t prove, it only fails to disprove. Medicine carries the same humility. We can say what usually happens in populations; we can trim the edges of uncertainty. But we can never hand a single patient certainty wrapped in percentages.

And yet the tyranny of the average still runs the show. It drives overtreatment — healthy people medicated because a number tipped over a line. It drives undertreatment — patients dismissed as “normal” while danger smolders beneath the surface. And it chips away at trust, because patients eventually realize the math doesn’t match their lives.

The tyranny isn’t going anywhere. Committees will keep moving the goalposts, journals will keep swooning over tidy p-values, and insurers will keep genuflecting to the curve.

But in the exam room, we can resist. Quietly, stubbornly. By remembering that thresholds don’t bleed, averages don’t grieve, and bell curves never ask, “Will it happen to me?”

Our job isn’t to medicate the graph. It’s to care for the person across the desk — the one who has never, not for a single day, been average.

I’ve never met Quetelet’s “average man.” If he ever shows up in the clinic, I’ll let you know. Until then, I’ll keep working with the real ones.

Great insight thank you.

bob

So true, so real. I’m a vet but find the same struggle. Many times I thought the same while in consult. Thank you for your insight.