Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

🎧 Available in audio

You can listen to this article, Brain Fog Nation – The Attention That Left Us, narrated in full. Whether you’re walking, driving, or just prefer to hear it aloud, click play below.

Note to the Reader

The people you’ll meet in these pages are not patients but composites — voices pieced together from medicine, conversation, and memory. Their stories are invented, yet they echo something real: what many call brain fog.

It is not a formal diagnosis. It has no lab value, no scan, no line in a textbook. It is reported, not measured — a lived experience of blurred thought, slowed focus, and slips of memory.

What follows is not a case series. It is a way of listening, from different angles, to something medicine has not yet learned how to name.

“We’ve become a society defined by distraction, acceleration, and mental erosion. The fog isn’t a glitch. It’s the weather report.”

The Fog Rolls In

The sky hung low. Grey. Damp. The kind of morning where Mt. Esja disappears — not gone, just hidden.

I watched from my office window. No wind. No sharp lines. Just a blurred outline of what should be clear.

That’s when I thought of Anna.

She came in that morning. Forty-nine. Healthy on paper, except for a family history of cardiomyopathy.

Composed. Capable. Careful with every word.

She looked up.

“My heart is fine,” she said. “It’s my brain I’m worried about.”

“I’m not sick. But I’m not… right.

I laugh. I function.

But it feels like—”

Her hand drifted in the air. Trying to catch something she couldn’t name.

She let it hang.

“I lose names I’ve known forever. Walk into rooms and forget why. I reread emails. I blank mid-sentence. It’s not anxiety. Not stress. Just fog.”

“When does it happen?”

“Afternoons, mostly. After multitasking. Sometimes I just… stop. My thoughts pile up like cars at a yellow light. It’s not memory loss. It’s slowed access.”

“Processing lag?”

“Yes. Still me. Just lagging.”

I’ve heard this before: people who pass every cognitive test, whose scans are clean, whose bloodwork is perfect. Not depressed. Not burned out. Just… not themselves.

Normal data. But something isn’t.

“Have you talked to anyone else about it?” I asked.

She half-smiled. “My GP said mindfulness. The neurologist blamed perimenopause — my hormones are ‘within range.’ A friend said stress.

“I even wondered if it could be Alzheimer’s. Early-onset. Or maybe long Covid. Some even say the vaccine. People whisper, but nobody really knows. I just want to understand what’s happening — and to know I’m not the only one.”

“You’re not,” I said. “Not even close.”

Friends. Colleagues. Patients.

All describe the same thing.

People who used to read books now skim headlines. Who forget mid-sentence. Who function just fine — on paper — but feel something slipping through the cracks.

We call it brain fog.

It’s not in the textbooks. But it’s in the waiting rooms, in the offices, in the quiet doubts of people who swear they’re fine.

Maybe that’s the problem.

And maybe it’s spreading.

The Provocateour in the Coffee Shop

The rain hadn’t let up.

I found a seat by the window. Gunnar was already there. Two black coffees on the table. His coat steamed gently, rain dripping from the hem. He looked older than last time — or maybe just more certain of himself.

“I ordered for you,” he said. “Still black, right?”

“Still black.”

We sat quietly, watching the street. People passed with hoods up, heads down, pushing through more than the weather.

“What do you think about brain fog?” I asked.

Gunnar stirred his cup. “Vague term. Which makes it useful. And dangerous.”

He sipped. “I assume you’ve seen more of it lately?”

I nodded. “Everywhere. People say they can’t focus. Lose words. Read the same message three times and still forget to reply.”

“Sounds like modern life.” He leaned back. Gunnar had once taught psychology, now mostly advising companies that claimed to value ‘deep work.’ He had a style — half therapist, half provocateur. Give him a few minutes, and he could argue almost anything into truth.

“But is it new?” I asked.

“The symptoms? No. The context? Yes.” He gestured at the street. “People used to complain about boredom. Now they complain they can’t hold a thought. We live in a world of interruptions. You pick up your phone to check the weather, but before you get there you’ve skimmed headlines, read about a celebrity death, and watched a dog save a goat. That’s not distraction.”

He let it hang, then dropped it like a verdict:

“That’s hijack.”

“But what does it do to the brain?”

“We used to focus on getting things done. Now we switch tasks to feel alive. Every scroll, swipe, or click gives a dopamine bump — not for solving anything, just for shifting attention. The brain rewires to prefer novelty over depth. Speed over clarity. Stillness starts to feel uncomfortable. Silence becomes friction. And thinking—real thinking—feels like work.”

He tapped his cup lightly. “That’s the cost. And it adds up.”

“It’s like a background hum,” I said. “Something you can’t turn off.”

“Exactly. That hum becomes normal. You stop noticing. But it shapes everything.”

He paused. “There’s a reason people describe fog as a place. It’s immersive. You don’t feel sick. Just off-track.”

The rain ticked against the glass.

“You know what the Greeks thought about memory?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“Mnemosyne — a goddess, the mother of the Muses. Without memory, there’s no art, no science, no history. Nothing human.”

He finished his coffee.

“So when memory weakens — not the facts, but the texture — we lose more than recall. We lose presence. Imagination. Meaning.”

“And brain fog?” I asked.

Gunnar gave me a sideways glance, the kind that dared you to argue.

“Maybe it’s not a glitch,” he said. “Maybe it’s a warning.”

The Hot Tub Confession

Steam rose from the water like something half-alive. The air was thick, salty, still. Fog clung to the world, softening everything into suggestion.

“Still working yourself to death?” Jonas asked, eyes closed, arms stretched along the rim of the tub.

“Only part-time,” I said, lowering myself in. The heat gripped my back, climbed my neck.

Jonas cracked an eye, grinned. “Bullshit. You’ve never done anything part-time in your life.”

He let his head drop back, still smiling.

Jonas was retired now. A legend on the golf course — three, sometimes four rounds a week. Everyone knew him. He knew everyone. His stories were old, but never stale. Details shifted, punch lines stretched, and somehow that only made them better.

“Feels like my brain doesn’t reload properly anymore,” he said suddenly. “Like a web page stuck at 82%.”

I laughed. “You too?”

“I blamed stress at first. But stress left, and it stayed.”

A seagull screeched behind us — sharp, insistent, like it had something urgent to announce.

“I started hiding the phone,” Jonas said. “Drawers. The garage. Once under a towel.”

“How long did that last?”

“Ten minutes. Once half a day. By evening I’d convinced myself half my friends had died and I just hadn’t seen the messages yet.”

I grinned. He didn’t.

“It’s like my attention isn’t mine anymore,” he said. “Like someone else is steering it — and I only notice once I’ve drifted.”

He stared into the gray distance. “Tried reading a book last week. First chapter in, my brain started twitching, like it was searching for the scroll bar. I used to read for hours. Now I skim sentences in my own head.”

We sat in silence. Not uncomfortable. Just real.

“Maybe it’s the Russians,” he said finally. “Some sabotage — hacking the Western mind one ping at a time.”

I chuckled. “If they are, they’re doing a damn good job.”

Jonas traced a hand through the steam. “It got bad last winter,” he said, almost casually.

“Bad how?”

He didn’t answer right away.

“That’s a longer story. But I’ll tell you this — when people say ‘fog,’ I know what they mean. It’s not a metaphor. It’s a place. And once you’re in it, you’re not sure you’ll find your way back.”

The seagull called again. Softer this time, as if it had changed its mind.

Jonas leaned his head back.

“Ever talk to Gunnar about this?” he asked. “Bet he’s got a theory.”

“I did. He always does.”

The Oslo Professor

He had winter in his eyes. That was the first thing I noticed — the way I’d once described him when we spoke about mTOR and the limits of human lifespan. His voice was clinical, his outlook unsparing.

Professor Einar Skoglund had recently retired from the University of Oslo after more than a decade as chair of biochemistry. We first met at a longevity symposium in Iceland. Now he was back, invited to lecture on brain aging — synapses, metabolism, and what happens when regulation falters.

We sat in a harbor café. The sea outside was flat and gray. He stirred his coffee slowly, then looked at me.

“You told me you were writing about brain fog — about attention, memory, and why people feel their minds slipping,” he said.

I nodded.

“Do you want the simple explanation, or the biochemical one?”

“Both.”

“Good. Because they are the same.”

He leaned forward.

“Think of attention not as a spotlight, but as a muscle. A muscle that tires, recovers, and fails if overused. Every time you shift tasks — app to message, notification back to work — the brain has to reset. That reset burns energy. Do it often enough, and the system becomes less efficient.”

He tapped his spoon against the cup.

“With repetition, the brain adapts badly. It lowers the threshold for switching. Focus weakens. Working memory slips. It’s like a conductor who stops keeping the orchestra in sync.”

He paused.

“Chemically, dopamine signaling wobbles. The control networks can’t hold steady. Sleep gets lighter. Memory consolidates poorly. And another system — the so-called default mode network — keeps intruding when it should quiet down. The brain isn’t actually tired. It’s noisy. And noise feels like fog.”

“People don’t describe it in those terms,” he added. “They just say: I can’t think.”

I nodded. “They call it fog.”

“Yes. But fog suggests weather — something that drifts in and lifts again. What if it isn’t weather? What if it’s residue? The smoke of chronic overload.”

He looked at me steadily.

“And the longer we feed the fire, the harder it will be to clear the air.”

The Doubter

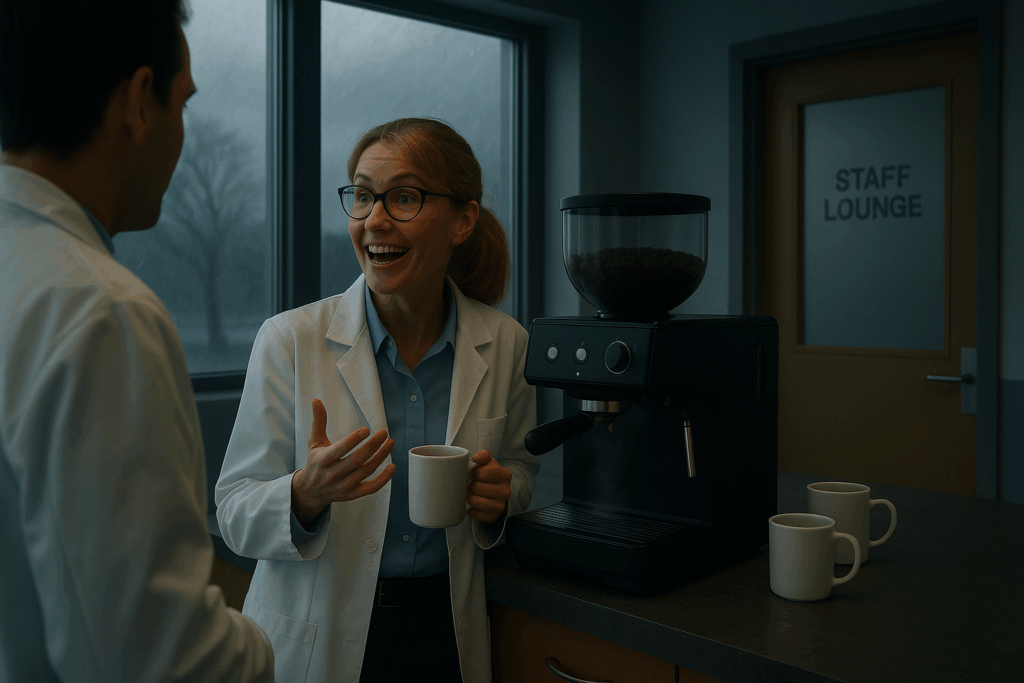

We were standing by the espresso machine in the staff lounge, waiting for the grinder to finish its rattling sermon. Outside, the wind slapped against the windows like it had something personal to settle.

“Fog?” Helga tilted her head, a hint of a smile tugging at the corner of her mouth. “You’re writing about fog now?”

Helga was a colleague — sharp, ambitious, and unflinchingly competent. The kind of doctor who’d been trained in an era of protocols and precision, where clarity was king and outcomes were measured in metrics. She didn’t waste words, and she didn’t chase shadows.

“I’ve been hearing it more,” I said. “People who feel… off. Slowed. Not depressed, not burned out — just foggy.”

She reached for a cup, turning it in her hand before setting it down again. “And you’re taking it seriously?”

Her tone was curious, but edged with disbelief.

“Of course,” I said. “It keeps coming up.”

Helga gave a short laugh, the kind that carried no warmth. “We used to call that life. Or not sleeping enough. Everyone feels tired. Everyone loses a word now and then. If we start pathologizing every lapse, we’ll end up writing prescriptions for Mondays.”

She paused.

“Don’t tell me you believe it’s the Covid vaccine. Or long Covid. Everyone wants a neat villain to blame.”

I said nothing, letting her run.

She went on. “Look — show me objective findings. Imaging, bloodwork, something measurable. Otherwise, you’re just chasing anecdotes. You know how medicine works: symptoms without markers don’t survive long. They fade, like all the other fashions.”

She poured her coffee, black, no hesitation.

“Honestly,” she added, softer now but still sharp, “you’re too smart for this.”

Then she left — coat swinging, heels clicking against the tile, her certainty trailing behind her like perfume.

The Question that Lingers

So, does brain fog exist?

Or is it just life? A byproduct of being alive in a world that won’t stop spinning. Helga would say it’s nothing more than tiredness. She might be right. Or she might be missing something.

We’ve tried to name it: cognitive fatigue, attention dysregulation, post-viral dysphoria, screen overload. None of it quite captures the lived texture — the way it blunts the edges, slows the fire, smudges the line between presence and performance.

At its simplest, brain fog is the name people give to lost clarity — slower thinking, weaker focus, more slips of memory. Not a disease. Not yet. But not nothing.

It’s a physiological response to interruption. To waking with alerts and falling asleep with glow. To toggling tabs and threads until the brain — built for depth — learns to operate in fragments.

Attention isn’t just something we give. It’s something we train. And we’ve been training it to fracture.

Studies show attention systems under strain. Constant digital input disrupts focus, weakens memory, and erodes the ability to think deeply. Dopamine patterns shift toward distraction. Even the “default mode” network — once linked to creativity and daydreaming — now intrudes when it shouldn’t.

Sometimes I wonder if we’ll adapt. If this fog is a clumsy transition, a temporary rewiring we’ll eventually master.

Other times, I look out the window.

And the mist still hangs over Mt. Esja.

Not dramatic. Not dangerous. Just there.

Softening the horizon.

Hiding the sharp edges.

We built a world too fast to think in — and called it progress.

But don’t worry. There’s probably an app for it.

Further Reading

-

Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(10):483–506.

– Key paper on the default mode network and its intrusion into task-related focus. -

Westbrook A, Braver TS. Cognitive effort: A neuroeconomic approach. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2015;15(2):395–415.

– Explains how dopamine and motivation affect attention and mental fatigue. -

Crivelli L, Palmer K, Calandri I, et al. Changes in cognitive functioning after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 May;18(5):1047-1066.

– Evidence that brain fog is measurable in post-COVID states. -

Ophir E, Nass C, Wagner AD. Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(37):15583–15587.

– Classic study: heavy multitaskers show weaker working memory and attention control. -

Firth J, Torous J, Stubbs B, et al. The “online brain”: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):119–129.

– Authoritative review of digital overload and cognitive impact. -

McEwen BS, Morrison JH. The brain on stress: vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course. Neuron. 2013;79(1):16–29.

– Explains how stress and overload reshape attention and memory systems. - Sigurdsson AF. The Code of Rejuvenation: To Cheat Death or Make Peace With It. DocsOpinion. 2025. – A narrative essay exploring longevity, attention, and the science of aging — where Professor Skoglund first appeared.

No, the fog didn’t come from ChatGPT. But it helped me name it.

This piece was developed with assistance from OpenAI’s language model, which contributed to language refinement, research support, and editorial suggestions — all under human supervision (and stubborn intuition).

Greetings, and thank you for your work. I can induce brain fog in myself by eating a heavy carbohydrate meal. Not a desired effect, just a repeatable and certain observation of losing both my vocabulary and my focus after a bready starchy meal. This is starkly noticeable because my day-to-day foods are very low carbohydrate. I have also observed that this effect is not transitory given weeks or months to acclimate to a starchy diet during travel, there is no acclimating. My head does not clear until I cut those foods.

Thank you Sigrid. That’s a striking observation — “post-meal fog” is something many people report. Rapid glucose swings after heavy carbs can affect clarity and focus. A good reminder that brain fog isn’t one thing but many pathways — metabolic, neurological, environmental — sometimes overlapping.

Another great piece, thank you!

I wouldn’t go as far as calling it fog, but for some time now I’ve been experiencing what I call “having too many tabs open in my head” — a sort of low-level overwhelm rooted in a vague sense that there’s probably something I should be attending to but don’t know what it is…

I recently attended a 5-day silent retreat. Upon arrival, we were urged to hand our phones to the retreat facilitators. This was optional and only five of 12 participants relinquished their phones (I was one of them). I’m so glad I did! I haven’t felt as clear, calm, and connected to the world around me in years! When my phone was returned to me on the final day, I didn’t switch it on for hours because I didn’t want to “break the spell.”

I did, if course, go back to using it, though I have become more aware of my triggers (boredom, loneliness, news addiction) and am training myself to recognize them before acting and respond by doing something *other* than reach for my phone. That always feels a little frustrating, with but after a few minutes I’ve moved on and no longer think of my phone (urge surfing).

I’m also re-training myself to read books — I used to be an avid reader, but over time became like the people you describe in your article. The first few weeks of reading books were a struggle; I decided to take out highly entertaining novels at the library, rather than the more sophisticated literature I would normally read, and to my delight, I am increasingly able to read for an hour or more without feeling in need to click or scroll anything. Yay, neuroplasticity! 😊

Conner, thank you for sharing this — your description of “too many tabs open in my head” is a vivid way of putting it, and probably closer to how many people experience it than the word fog. Your retreat story is striking: simply handing over the phone showed how quickly clarity can return when the interruptions fall away. And your effort to retrain yourself to read again is a reminder that attention is not only fragile, but trainable. Neuroplasticity works both ways. I also know you’ve written thoughtfully about food and health yourself, so it means a lot to me that this piece resonated with you.

Great reminder about avoiding mental fog. The brain needs a lot of rest, just like the body does. I remember a study that showed that 5 hours a day is the optimum amount for mentally involved work such as research or creative endeavors, and anything more than that won’t add any value.

I also read that what people call multitasking is actually task switching. Your brain can’t do 2 things at once, so it keeps switching between tasks, and it’s very stressful.

Sometimes I’m doing a mentally challenging project, and my brain just can’t continue. Even though I want to continue, I just have to accept defeat for the day, and continue it the next day when my brain is refreshed.

Another strategy I use when doing mentally involved work is to take half hour walks throughout the day.

I’m also not on social media, and limit browsing on the internet. Researchers design sites to keep you on their sites as long as possible. After a few hours of that, you will have used up your brain energy for the day.

For me it used to be FOMO (Fear of missing out), but now it’s JOMO, the joy of missing out.

Thank you Andy — this is a wonderful reminder that the brain, like the body, needs structured rest. I like how you put it: there’s a point where pushing harder adds no value, and recovery is what restores clarity. You’re also right about multitasking — it’s really just task switching, and every switch carries a cost. I especially appreciate your shift from FOMO to JOMO. That captures something essential: sometimes clear thinking comes not from doing more, but from choosing less.