Estimated reading time: 19 minutes

The sun hung low over the Santa Ynez Mountains, casting long shadows across the California hills. Ronald Reagan sat tall in the saddle, reins loose in his weathered hands. He still rode most mornings—slowly, deliberately—but with the easy grace of a man who had spent a lifetime playing cowboys and governors and presidents, until the roles became indistinguishable from the man.

But this morning was different.

He paused at a ridge, gazing toward the Pacific. His hand tightened on the reins. Then came the hesitation—not from the horse, but from something quieter: he couldn’t remember what came next. The trail. The turn. The word for canyon.

Earlier that morning, he had forgotten the name of his favorite trail. The word sat just out of reach, familiar and foreign all at once.

Later, the television played one of his old movies—Knute Rockne, All American. Reagan sat still as the black-and-white image flickered across the screen. A younger version of himself appeared—confident, magnetic, delivering the line that made him famous:

“Win one for the Gipper.”

Nancy stood quietly in the hallway, watching the flicker of the screen light his face. He didn’t react. And for the first time, she wondered, softly, painfully, if the man on the screen was someone he remembered.

To millions of Americans, he would always be The Gipper—a nickname born from that role, where he played George Gipp, Notre Dame’s golden-boy football star. The line became a kind of prophecy, a call to courage in moments of doubt. Over time, it fused with Reagan himself: the fighter, the optimist, the one who stood tall even when the odds were stacked.

Then came the letter. The ink was neat. The words were simple. The message was seismic:

“I now begin the journey that will lead me into the sunset of my life.”

On November 5, 1994—nearly six years after leaving the White House—Ronald Reagan, actor, governor, two-term president, Cold War Warrior, American icon, announced he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The letter was direct, sunny, stoic. It bore the voice of a man who had long mastered public performance. But between the lines, something quieter trembled.

He signed the letter himself. At the time, he still could.

In the months that followed, the world changed how it remembered him. The Gipper. The Great Communicator. The man who beat the bullet. The man who beat the Soviets. The man who brought America back.

But over time, behind closed doors, Ronald Reagan was slowly forgetting all of it.

Alzheimer’s: The Name Behind the Disease

The disease was first described in 1906 by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist. He presented the case of a woman who suffered from severe memory loss, confusion, and hallucinations. After her death, he examined her brain and discovered the now-recognized hallmarks: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

Today, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, slow, progressive, and irreversible. It affects millions, stripping away memory, language, and, eventually, independence.

The Day the Bullet Nearly Won

March 30, 1981.

Just 69 days into his presidency, Ronald Reagan stepped out of the Washington Hilton after delivering a lunch speech. He waved. Smiled. Turned toward the limousine.

Then came the shots.

Six bullets in 1.7 seconds. It didn’t sound like gunfire. More like popping balloons. Then: chaos. Screams.

Jerry Parr, the lead Secret Service agent, moved instantly. He shoved Reagan toward the car and threw himself on top. Behind them, the world buckled.

Officer Thomas Delahanty dropped, clutching his throat. Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy staggered, wounded. Press Secretary James Brady collapsed, gravely injured. In seconds, the pavement bore witness to the cost of chaos.

Inside the limo, Reagan thought it was fireworks. He smiled faintly.

“You okay, Mr. President?”

“I think so,” he said. But the breath came tight. Then a cough. Then blood.

He turned to Parr. “I think you better get me to a hospital. I’m having trouble breathing.”

The car peeled away from the Washington Hilton and raced toward George Washington University Hospital.

Reagan walked into the ER under his own power. Seventy years old. Bleeding into his chest. Minutes later, he collapsed.

Surgeons discovered the bullet had ricocheted off the limousine, entered under his left arm, torn through a lung, and lodged near his heart. He had lost half his blood volume. Still, he joked: “I hope you’re all Republicans.”

They opened his chest. Stopped the bleeding. Repaired the lung.

Nancy arrived, pale as paper. Reagan saw her, smiled through the oxygen mask, and rasped, “Honey, I forgot to duck.”

He survived. Barely.

So did the others—but not untouched.

Officer Thomas Delahanty was shot in the neck. His nerves were ruined. He never returned to duty.

Tim McCarthy, a Secret Service agent, had spread his arms to shield the president. A bullet pierced his chest, missing the heart. He recovered and returned to work.

Press Secretary James Brady was not so lucky. A bullet shattered his skull and damaged his brain. He lived, but could not walk, or speak clearly, or feed himself. His wife, Sarah, became his advocate. Together, they lent their names to the Brady Bill—a landmark law passed in 1993 that mandated federal background checks for handgun purchases and became a cornerstone of modern gun control efforts in the United States.

The shooter, John Hinckley Jr., had fired to impress actress Jodie Foster. His bullets shattered bodies, shifted lives, and nearly rewrote history.

But they didn’t.

Instead, the moment was recast in myth: Reagan the resilient. Reagan the gallant. Reagan, rising from the gurney with a joke on his lips.

He hadn’t just survived.

He had turned crisis into composure, pain into resolve.

And in doing so, he became a legend.

Resurrection and Re-election

The bullet had come within an inch of his heart.

But just weeks after the assassination attempt, Ronald Reagan returned to the White House. He was thinner, slower, a little more winded on the stairs—but triumphant. The headlines hailed his resilience. Approval ratings soared. Americans love a comeback, and Reagan had staged a near-miraculous one.

From the hospital bed to the podium, the transformation was swift and strategic.

His team understood the stakes. The footage of him waving from the window, making light-hearted remarks to nurses, even signing legislation from his recovery bed—all of it fed a singular narrative: strength. Vitality. Leadership that could not be shaken by a madman’s gun.

But behind closed doors, there were days he felt the aftershocks. Fatigue lingered. Focus wavered. His schedule was trimmed, then trimmed again. Still, he smiled for the cameras. He joked. He reassured.

When he returned to Congress just weeks later, he received a standing ovation. His speech was light on policy but heavy on tone: optimism, recovery, a nation not bowed by violence.

By 1984, he had fully weaponized this image of restored strength.

The campaign against Walter Mondale was one of contrast: Reagan’s sunny certainty versus Mondale’s sober warnings. Reagan’s age—then 73—became a campaign issue after a faltering debate performance. He appeared tired, confused. For a moment, the veneer cracked.

But in the next debate, Reagan delivered the line that would define the election:

“I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

Even Mondale laughed. And in that moment, the race was over.

He won 49 states. A landslide. A mandate.

The Great Communicator had done it again—spoken past policy, past data, and directly to the American imagination.

But behind the scenes, some staffers had begun to notice little things: missed cues, wandering thoughts, moments of blankness brushed aside with a joke.

Still, there was no room for doubt.

Not yet.

Iran, Memory, and the Crisis of Trust

The second term began with momentum, but it wouldn’t last.

By 1985, Reagan’s public appearances still carried polish, but those closest to him noticed something else. There were pauses where none had been before. Repetitions. Names he struggled to recall. At times, he would stare into the middle distance just before a camera went live. Some aides called it fatigue. Others weren’t so sure.

Then came the scandal.

The Iran-Contra affair unfolded like a slow-moving storm. Behind closed doors, Reagan’s administration had secretly sold weapons to Iran—violating an arms embargo—in hopes of securing the release of American hostages. The profits from those sales were then funneled, illegally, to support the Contras, a right-wing rebel group in Nicaragua. Congress had expressly forbidden this kind of support. The scheme bypassed oversight, blurred legal lines, and operated in the shadows.

When the story broke in late 1986, it triggered the most profound crisis of Reagan’s presidency. The man long admired for his clarity and conviction now appeared hesitant, imprecise. In a nationally televised address, he insisted: “I did not trade arms for hostages.” But soon after, he added: “My heart and my best intentions still tell me that’s true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.”

The contradiction became infamous. To critics, it was a confession wrapped in denial. To supporters, it sounded like something more troubling—a man struggling to hold the line of a story even he no longer fully grasped.

Even among his most loyal allies, the whispers began. Was this deception? Or was it the early shadow of something more profound?

A blue-ribbon commission launched an investigation. Congressional hearings followed. Staffers resigned. Lt. Col. Oliver North became a household name. Reagan’s poll numbers dipped. Trust eroded. Behind the scenes, aides trimmed his schedule, shortened briefing materials, and increasingly took decisions off his desk.

Still, Reagan smiled for the cameras, joked with reporters, and gave speeches. But the scaffolding around him had thickened.

Iran-Contra didn’t destroy his presidency. In time, his approval ratings rebounded. But something had changed. A fracture—quiet, unspoken—had opened up beneath the image.

And in the West Wing, a new kind of whisper surfaced:

Maybe the bullet in ’81 wasn’t what nearly undid Reagan. Perhaps it was time itself.

The Words Begin To Slip

For a man known as The Great Communicator, words weren’t just tools—they were the architecture of his presidency. Reagan led with language. His speeches could lift a room or disarm a critic. Few presidents have been so defined by how they spoke.

But the decline began before anyone knew its name.

Years before his public Alzheimer’s diagnosis in 1994, the signals were already there—subtle, but accumulating.

Not in the message—at first—but in cadence. In fluency. In the quiet erosion of spontaneous speech.

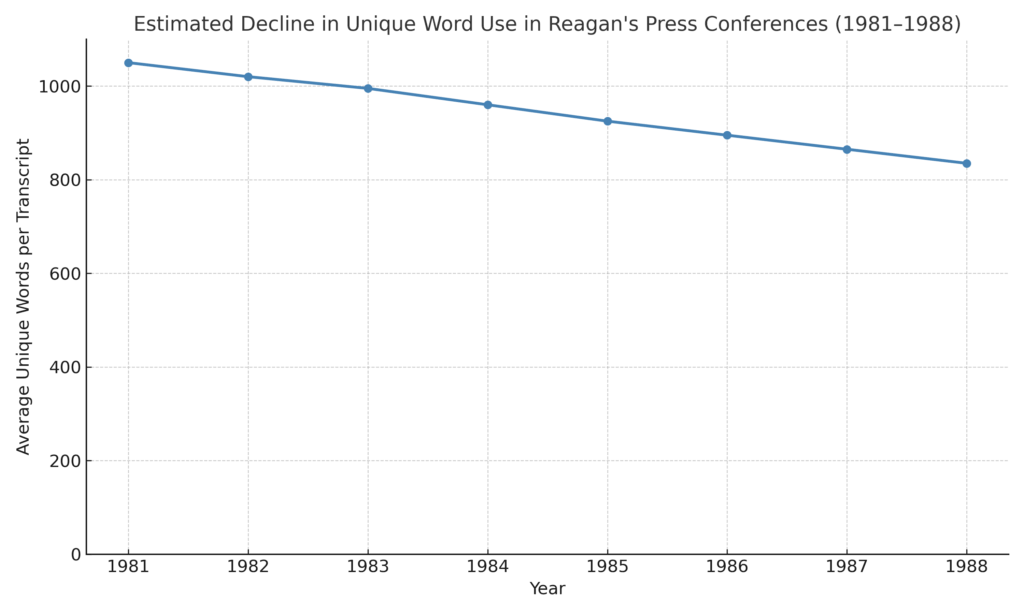

In 2015, researchers led by Berisha, Slüer, and Wang analyzed Reagan’s press conference transcripts throughout his presidency. Their findings were striking:

“Changes in speaking patterns were becoming detectable years prior to clinical diagnosis.” — Berisha et al., 2015

Over time, his vocabulary narrowed. He relied more on vague terms—“thing,” “something”—and filled pauses with verbal tics. These weren’t dramatic lapses. They were microfractures in a voice that once commanded nations.

To separate aging from illness, researchers compared Reagan to George H. W. Bush. Bush’s speech remained stable. Reagan’s showed clear signs of decline.

And there may have been clues even earlier.

In 1980, psychiatrist Louis Gottschalk used a verbal behavior scoring system to analyze Reagan’s debate performances. He saw patterns of impairment—repetitions, abandoned thoughts, reduced complexity.

“Reagan’s language showed signs of mental decline as early as 1980.” — Dr. Louis Gottschalk

Viewed live, these changes were easy to miss, softened by his warmth, timing, and script. But in hindsight, the pattern emerges.

The narrative we know begins with his 1994 letter. But the private unraveling may have started much earlier—not in the garden, but behind the podium.

And that leads to a harder question:

What did we miss—because we didn’t know how to see it, or didn’t want to?

Based on findings from Berisha et al. (2015), reduced lexical diversity may reflect early signs of cognitive impairment, years before clinical diagnosis.

Reykjavik and the Statesman’s Last Stand

And yet, despite the gathering shadows, Reagan had one final summit to climb.

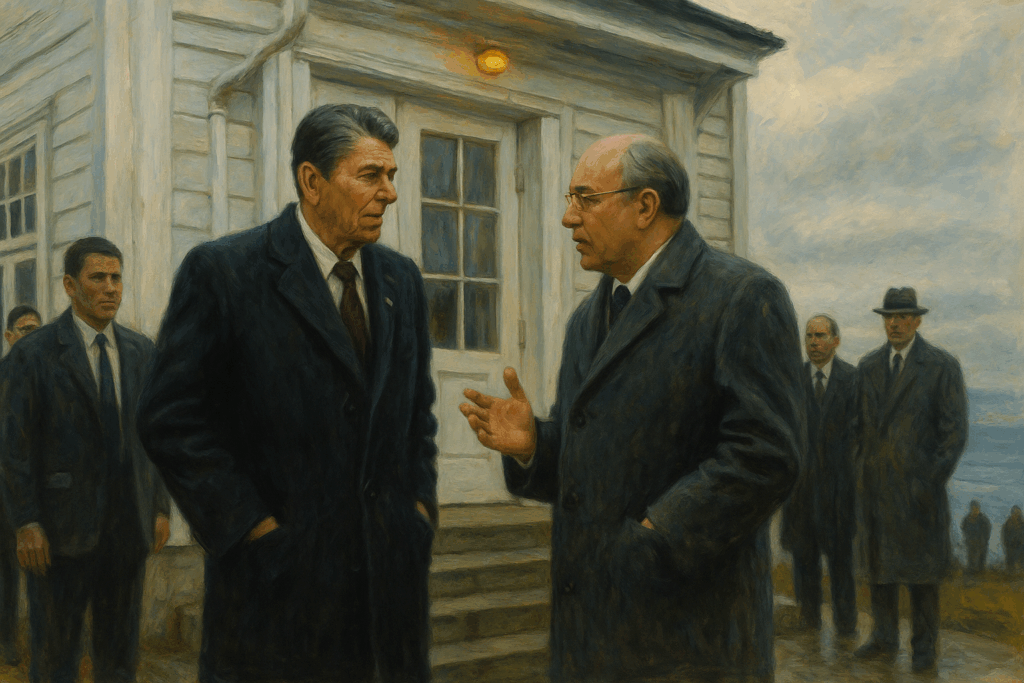

In October 1986, just months after Iran-Contra began to unravel, he boarded Air Force One and flew north, toward a cold, windswept city perched on the edge of the Atlantic. The Reykjavík Summit was supposed to be a routine affair. It became something else entirely: a glimpse of peace between two aging empires, and two men trying to rewrite the future.

Reagan had come to office denouncing the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” But in his second term, something shifted. An unexpected understanding began to take shape between Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. The two met in Reykjavík, Iceland, in October 1986. What was meant to be a modest summit turned into something historic.

Inside a plain white house by the sea, over two days of intense talks, they discussed slashing their nations’ nuclear arsenals. At one point, Reagan even proposed eliminating all nuclear weapons. Gorbachev was intrigued. But the deal collapsed over a single sticking point: Reagan’s refusal to abandon the Strategic Defense Initiative—a proposed space-based missile defense system aimed at neutralizing incoming nuclear attacks, often mocked as “Star Wars.”

The summit ended without an agreement. Yet it marked a turning point.

“I came away with a feeling that we had been on the verge of something very important,” Reagan later said. Gorbachev would echo the sentiment: “We both realized we could not go back to the way things had been.”

The candor between the two leaders laid the foundation for the INF Treaty signed the following year—a landmark agreement that began the actual dismantling of nuclear stockpiles.

In that same spirit, a year later, Reagan stood before the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin and delivered one of the most famous lines of the Cold War:

“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

It was more than a soundbite. It was a declaration of defiance and hope, delivered with conviction that surprised even his own advisors, many of whom had lobbied for softer language.

But Reagan knew the power of a single line. He had spent a lifetime delivering them.

Two years later, the Berlin Wall would fall.

And the man once dismissed as simplistic, too ideological, or too old, was suddenly seen as a visionary. The world didn’t just remember his policies—it remembered his tone, his optimism, his resolve.

But even as his vision expanded across continents, something closer to home was quietly retreating.

He began forgetting meetings—names he’d known for decades, now stranded on the tip of his tongue. Staffers noticed. They shortened memos, simplified briefings, revised his schedule. During press events, he leaned more heavily on cue cards. In private, his signature began to tremble.

It wasn’t a dramatic unraveling. It was a dignified drift. And those closest to him began to sense the widening gap between the man on stage and the man behind the scenes.

He had stood tall in Reykjavík, in Berlin, and in the imagination of a world that dared to believe peace was possible.

But in the quiet halls of the White House, the Gipper had started to forget his lines.

Fading Light

After leaving office in January 1989, Ronald Reagan returned to California a revered statesman. The sun seemed to set gently on his presidency, and for a time, he basked in it. He gave speeches, wrote his memoirs, opened a presidential library. His jokes were still sharp. His charm, intact.

But even then, something had started to fray.

There were pauses in the conversation. Notes repeated. Appointments missed. Those closest to him noticed the change, small at first, but accumulating. Nancy noticed most of all.

One day, he misplaced his riding gloves. The next, he couldn’t recall the name of a longtime friend. When asked about a former aide, he smiled, uncertain.

Even as his memory dimmed, the myth endured. The speeches continued to be featured on cable documentaries. The quotes were stitched into textbooks and echoed at party conventions.

“America is too great for small dreams.”

It was one of his favorite lines—an invocation of hope, vision, and scale. And it stood in tragic contrast to the shrinking scope of his final years.

The public announcement in 1994 brought it into the open—Alzheimer’s. The Sunset of his life, he had called it.

From then on, his appearances became increasingly rare. His words are fewer. The man who had once spoken for a nation now sat quietly in the garden, watching the light change.

Yet even in silence, his presence lingered. Visitors to his library left notes. Letters poured in. Some thanked him. Others shared their own Alzheimer’s stories. A quiet fellowship had formed, bound by memory and its loss.

In those final years, Reagan no longer spoke the great lines. But the country remembered them for him.

By then, the euphemisms had worn thin. The pauses were no longer explained away. It was Alzheimer’s. Not forgetfulness, not fatigue—but a disease that strips the mind while leaving the body waiting.

The Long Goodbye

Unlike other dementias, Alzheimer’s often begins quietly—a forgotten name, a repeated question. Over time, it confuses chronology, fractures language, and dulls recognition. Long-term memories sometimes persist, even as the present unravels.

For Reagan, the movie roles may have outlasted the meetings. The cowboy may have stayed long after the governor was gone.

Alzheimer’s doesn’t take everything at once. It takes what wounds most intimately: the ability to know who you are.

He Never Lost the Twinkle In His Eye

“There was still a spark,” George H. W. Bush recalled after visiting Ronald Reagan in Bel-Air. “He never lost the twinkle in his eye.”

By then, Reagan no longer remembered meetings or names the way he once had. But that quiet charm—the warmth, the instinct to reassure—still flickered, however faintly.

There were visitors: former aides, old friends, foreign leaders. Some described moments of clarity—others, of gentle confusion. One staffer remembered sitting beside him in the garden. “He looked at me like he was trying to place a name to a face he once knew well. But then he just smiled and said, ‘You know, this is a good place to sit, isn’t it?’”

Margaret Thatcher visited during one of his quieter days. “He always remembered how to make you feel welcome,” she said, “even when he no longer remembered exactly who you were.”

Together, these recollections sharpened the contrast between the two Reagans: the man on stage and the man in the garden. The one who delivered lines to history. The one who could no longer remember them.

Reagan remains a paradox—lionized and lampooned, underestimated and beloved. To some, he was the actor who played president. To others, the president who remade the world.

But Alzheimer’s blurred the boundaries. It stripped away office, title, and performance—and left behind something unexpected: empathy.

In that empathy, something deeper took root: a recognition that even legends are not immune to forgetting.

Epilogue -The Mind of a Nation

Years later, the questions still linger.

What did he know—and when did he forget it?

As the disease progressed, Reagan’s slow withdrawal became a national reckoning. Americans who had grown up watching him now watched him vanish. Memory by memory. Word by word.

His decline, once whispered about, became a symbol. Of aging. Of loss. Of what it means to fade while the world remembers you at full light.

In a country that worships youth and power, Reagan’s final decade offered something else: a reminder of fragility. The man who once declared:

“Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Now he depended on others for every basic need.

And yet Nancy stayed. His staff stayed. The image stayed.

At the time of Reagan’s diagnosis in 1994, treatment options were limited. Thirty years later, the picture is more hopeful—but still uncertain. While there is still no cure, researchers have gained ground. We better understand the roles of amyloid plaques and tau tangles—the proteins most associated with Alzheimer’s. Newer therapies aim to slow progression, not reverse it, and debates about their safety and efficacy continue. But the attention Reagan brought to the disease helped usher in an era of more robust funding, scientific urgency, and public awareness.

The mind remains medicine’s final frontier. And Reagan’s story helped strip away the stigma. His illness, once spoken of in whispers, became a national conversation. The emotional burden carried by families, especially caregivers, gained visibility. Nancy Reagan’s journey became emblematic of the silent resilience required.

She often spoke of the pain of watching him slip away—not all at once, but in fragments. Her experience echoed that of millions.

In his final years, Reagan no longer delivered lines. He sat quietly in the garden, where memory came and went with the wind.

This article is dedicated to those living with Alzheimer’s, and to those who never stop loving them.

Next in the Series

Power isolates. Pressure distorts. And in the sleepless hours of the night, even a president can come undone.

In Episode 7, we turn to Richard Nixon—a man consumed by enemies, real and imagined. As paranoia deepened and trust vanished, the tape recorder continued to run. And the unraveling began.

Coming soon:

The Heart of Power – Richard Nixon: The Enemy Within

Previous:

Episode 1. The Heart of Power: When Metabolic Disease Entered the Oval Office – William Howard Taft

Episode 2. The Heart of Power: The Golf Course Heart Attack – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Episode 3. The Heart of Power: The Stroke That Silenced a Dream – Woodrow Wilson

Episode 4. The Heart of Power: Built To Stand, Bound To Fall – John F Kennedy

Episode 5. The Heart of Power: Where Strength Sat Still – Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Sources & Further Reading

🧠 Alzheimer’s, Memory, and the Long Goodbye

- Sigurdsson, Axel F. “Dementia – Cognitive Impairment.”

- Reagan’s Letter Announcing His Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

- The Long Goodbye: Memories of My Father – Patti Davis, 2004

- Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures – Alzheimer’s Association

- The Problem of Alzheimer’s – Jason Karlawish, 2021

- Nancy Gibbs. March 6Remembering Nancy Reagan: The End of a White House Love Story

- Lawrence K. Altman, REAGAN’S TWILIGHT — A special report.; A President Fades Into a World Apart

🗣️ Early Cognitive Signs and Language Analysis

- Berisha V, Wang S, LaCross A, Liss J. Tracking discourse complexity preceding Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: a case study comparing the press conferences of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Walker Bush. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(3):959-63. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142763. PMID: 25633673; PMCID: PMC6922000.

- Gottschalk, Louis A. Content Analysis of Verbal Behavior – New Findings and Clinical Applications. First Published 1995. eBook Published February 24, 2014

🔫 Assassination Attempt, 1981

- Dan Rather: Breaking News – The Reagan Assassination Attempt

- The Assassination Attempt Exhibit – Reagan Library

- March 30, 1981 – U.S. Secret Service. In Remembrance: Forty Years Since the Assassination Attempt on President Reagan

- Rawhide Down – Del Quentin Wilber, 2011

🗳️ 1984 Re-Election and Public Image

- 1984 U.S. Presidential Election – Britannica

- 1984 Election Results – The American Presidency Project

- ⚖️ Iran-Contra Affair

- PBS: Reagan and the Iran-Contra Affair

🕊️ Cold War, Reykjavík Summit, and the INF Treaty

- Reagan and Gorbachev – Atomic Heritage Foundation

- The Reykjavík Summit – The Reagan Vision

- Reagan and Gorbachev: How the Cold War Ended – Jack F. Matlock Jr., 2004

- An American Life: The Autobiography – Ronald Reagan, 1990

- Memoirs – Mikhail Gorbachev, 1996

Some portions of this article were developed with support from ChatGPT, an AI tool created by OpenAI. It was used to assist with research synthesis, narrative structure, and language refinement. All medical content, historical analysis, and editorial decisions were independently reviewed and finalized by the author.

I remember him as being the man who brought optimism to America. Made me feel we could do anything we put our minds to, and made me look forward to the future. After he retired I got to see him and Nancy light the Christmas tree at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. He didn’t make any speeches, but it was nice to see him in an intimate setting, and at a close distance.

My Mom had vascular dementia for the last decade of life. Her doctors said it was caused by mini strokes in the brain. Probably preventable if she had good cholesterol counts and blood pressure numbers. Blood vessels carry nutrients and oxygen to the brain, and also remove the brains waste products. It’s easy to imagine what happens when these tiny blood vessels and capillaries get clogged. It’s probably a major factor in Alzheimer and other types of dementia.

Thank you for sharing such a personal and heartfelt memory. The image of Reagan and Nancy quietly lighting the Christmas tree, long after the speeches were over, says so much—about dignity, presence, and how even in silence, he still meant something to so many.

I’m also sorry to hear about your mother’s journey with vascular dementia. You’re absolutely right—our brain health is intimately tied to the health of the blood vessels that nourish it. Just like in the heart, those tiny vessels in the brain can suffer from years of untreated high blood pressure, cholesterol imbalance, and inflammation. It’s one of the reasons cardiologists today often say, “What’s good for the heart is good for the brain.”

Reagan biographer Edmund Morris spent nearly every day with Reagan since at least his first day as President. He said he noticed a decline in Reagan’s mental acuity following the assassination attempt.

That’s an important point Kevin — thank you for sharing it. Edmund Morris’s unique position as Reagan’s authorized biographer gave him rare access, and his comment adds weight to a longstanding and sensitive question: did the 1981 assassination attempt mark the beginning of Reagan’s cognitive decline?

In fact, Morris wrote in Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan, that after the shooting, Reagan “never seemed quite the same.” While the statement is subtle, it aligns with other reports that noted changes in his focus, energy, and conversational sharpness after the event. Some have speculated that the trauma and blood loss may have played a role, especially considering Reagan was nearly 70 at the time—a vulnerable age for cerebral resilience.

Maybe I’ll weave this into the article.